Brain Scans Reveal Difference Between Neanderthals and Us

Neanderthal newborns had similar brains to human infants, though just after birth stark changes began to set in, so that by 1 year old the two children would've had very different noggins and may have even viewed the world differently, researchers now say.

These new findings could shed light on how our closest extinct relatives might have thought differently than us, and reveal details about the evolution of our brain.

Past studies of Neanderthal skulls revealed their brains were comparable in size to ours. This suggested they might have possessed mental capabilities similar to modern humans.

Still, the brains of adult Neanderthals were a different shape than ours — theirs were less globular and more elongated. This elongated shape was actually the norm for more than 2 million years of human evolution, and is seen in chimpanzees as well. [10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain ]

Comparing scans

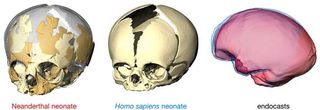

To learn more about when differences in brain shape first started appearing in development, researchers created virtual imprints of 11 Neanderthal brains, including a newborn, based on CT scans of their skulls.

The brains of newborn Neanderthals and human infants are about the same size, and both had relatively elongated braincases, likely to help fit through the birth canal, which is roughly similar in shape in both species. After birth, however, and especially in the first year of life, our brains and theirs start to diverge, with those of modern humans becoming more globular.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I was surprised to see how strong that difference was, even though modern humans and Neanderthals are so closely related, and the genetic differences are so minor," researcher Philipp Gunz, a paleoanthropologist at Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology at Leipzig, Germany, told LiveScience.

Modern humans therefore depart from an ancestral pattern of brain development that separates our own species from chimpanzees and all fossil humans, including Neanderthals. The overall shape of the brain probably does not have too much significance in and of itself toward brain function, "but I would say that it does reflect changes in the pattern and timing of the growth of the underlying brain circuitry," Gunz said. This internal organization of the brain is what matters most for mental ability.

"In modern humans, the connections between diverse brain regions that are established in the first years of life are important for higher-order social, emotional, and communication functions," Gunz said. "It is therefore unlikely that Neanderthals saw the world as we do."

Gene differences

This new view on human brain development might help to explain the results of a recent comparison of Neanderthal and modern human genomes.

"Only a few genes separate modern humans from Neanderthals, some of which are related to the brain," Gunz said "What our results suggest is that these genes might be linked with the speed and pattern of brain development."

It is important to note "that all interpretations about Neanderthal cognition will always be somewhat speculative," Gunz cautioned. "What our research could allow is to study what separates modern humans from Neanderthals, to learn something about ourselves and maybe something about Neanderthals as well."

The scientists detailed their findings in the Nov. 9 issue of the journal Current Biology.