Mystery Book Gives Up a Secret

One of the most mysterious books in the world has given up one of its secrets: its age. Researchers at the University of Arizona have finally dated the book to the early 15th century.

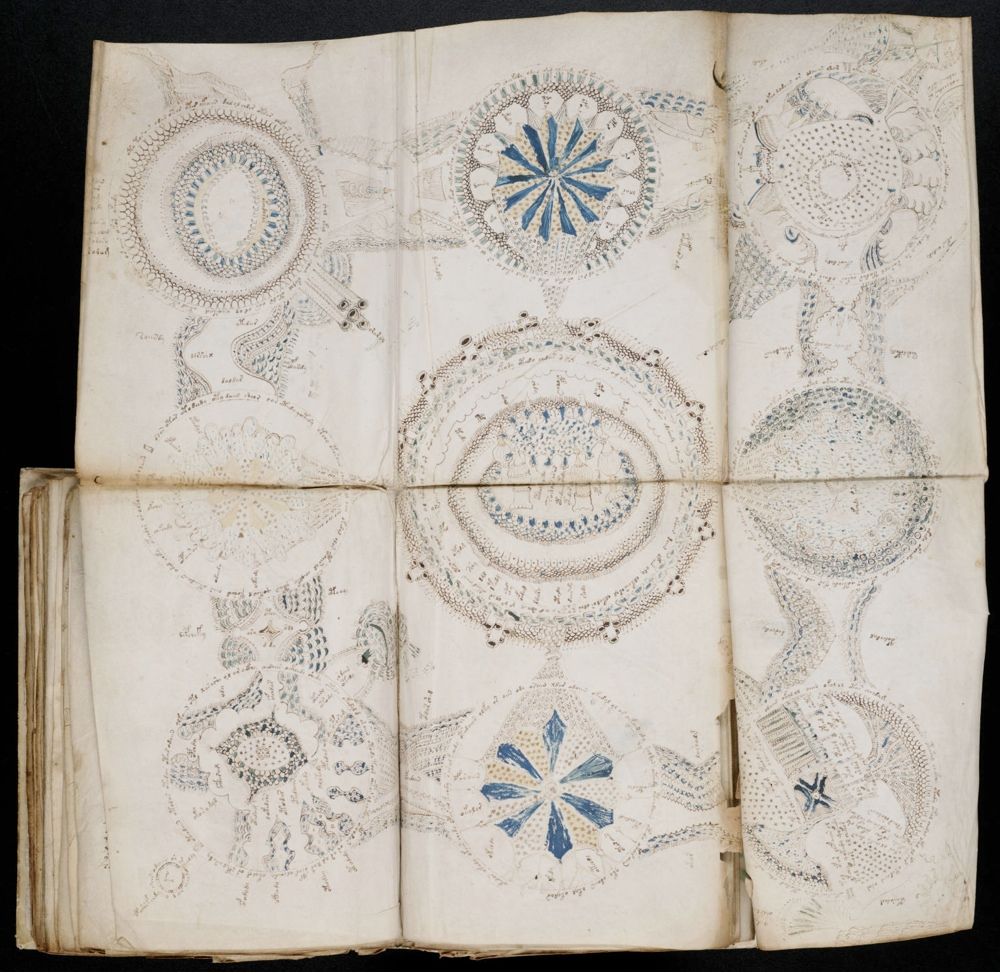

The mystery book, called the Voynich manuscript, is written in a language that no one can read and hasn't been found anywhere else. It is also full of drawings of objects resembling plants, ancient lab equipment and cosmological signs — there are even illustrations of women in baths. None of the plants are clearly identifiable, and many seem to be odd compilations of different root and leaf systems.

No one is able to read the book because it's not written in a known language — although it seems to have been a true language based on an analysis of the characters, the researchers said, adding that the writing style suggests the author was fluent in whatever language it was. It's even possible that the language was made up as a cipher to hide the true meaning of the texts, a tactic that became popular in the 1600s.

"Who knows what's being written about in this manuscript, but it appears to be dealing with a range of topics that might relate to alchemy. Secrecy is sometimes associated with alchemy, and so it would be consistent with that tradition if the knowledge contained in the book was encoded," study researcher Greg Hodgins said in a statement. "What we have are the drawings. Just look at those drawings: Are they botanical? Are they marine organisms? Are they astrological? Nobody knows."

"This rules out one of the names most often mentioned as a possible author, Roger Bacon, as he lived in the 13th century," dead languages researcher Gonzalo Rubio of Pennsylvania State University told LiveScience in an e-mail. "Moreover, this also rules out most of the possible 16th- and 17th-century authors, as well as the possibility of a modern forgery perhaps by Wilfrid Voynich himself," said Rubio who was not involved in the study.

Hodgins and his team dated the book by looking at its levels of the radioactive element carbon-14, which is an isotope of carbon. Isotopes have the same number of protons in their atomic nuclei but different numbers of neutrons. Most of the carbon in the Earth is carbon-12.

As plants take carbon dioxide from the air to carry out photosynthesis and grow, they incorporate relative amounts of the different isotopes into their tissues. And when they die, the level of carbon-14 in the plant decays at a predictable rate, and so can be used to calculate the amount of time that has passed since death.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Because the book is made out of vellum, which is a specially treated animal skin, carbon dating can determine its age. This method is accurate for objects dating back around 60,000 years, when the carbon-14 levels get too low to detect.

To date the manuscript, Hodgins removed four thin, inch-long strips of the vellum from the outside of pages that weren't likely to have been rebound. He

then cleaned the strips to remove finger oils or dirt that had collected over the years. They were then incinerated to remove everything but the carbon in the sample, which was then tested for carbon-14 levels.

"I find this manuscript is absolutely fascinating as a window into a very interesting mind," Hodgins said. "Piecing these things together was fantastic. It's a great puzzle that no one has cracked, and who doesn't love a puzzle?"

While knowing the date of the book helps put one of the pieces of that puzzle in place, it's possible its complete meaning will never be deciphered. The key to the book's code could have been destroyed long ago, making it impossible to crack. The latest computer programs and cryptographers can't decipher its meaning, but there is hope that future technologies could crack this mystery book's code, the researchers said.

You can follow LiveScience Staff Writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Most Popular