7 Ways the Mind and Body Change With Age

Lots of changes

The poster child of aging seems to be a wrinkly-faced, forgetful, grumpy old man. But science is painting another, more in-depth picture of aging Americans. The elderly tend to become more happy, liberal and in many cases remain pretty darn sharp. Here are 7 ways we change as we get older.

Lean liberal

As wrinkles set in, so do a person's rigid beliefs, many people have long assumed. Not true, according to a survey of more than 46,000 Americans between 1972 and 2004. While the study didn't follow individuals as they aged, the results represent snapshots of the changing attitudes of respondents in different age groups. Over time, adults' attitudes got more liberal regarding politics, economics, race, gender, religion and sexuality issues. While the results don't mean your grandma is sure to revert to hippie-dom, on average older adults will head in that direction.

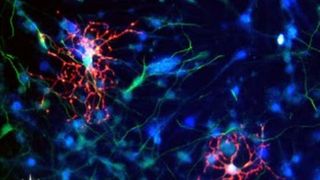

Your stem cells age, too

Beneath the sagging skin, the body's cells are also deteriorating. Stem cells, thought to combat aging by replenishing old or damaged cells, also succumb to the wear and tear of aging. Research published in the journal PLoS Biology in 2007, suggests stem cells' regenerative capacity declines as one ages.

In the study, researchers looked at stem cells that give rise to bone marrow that had been isolated from young and old mice. The cells were transplanted into mice whose bone marrow cells had been destroyed.

At first, both young and old stem cells churned out new cells at about the same rate; but later, the old stem cells' repopulating ability dropped off considerably compared with their young counterparts. The scientists suspect genetics is at play, as genes for stress and inflammation became more active in these stem cells with age.

Need less sleep

In a study of 110 healthy adults who were allowed eight hours of bed time, the oldest group (ages 66 to 83) snoozed about 20 minutes less than the middle-agers (ages 40 to 55), who in turn slept about 23 minutes less than the youngest group (ages 20 to 30). The simplest explanation for the fewer shut-eye minutes: Older adults need less sleep.

Another explanation, and one supported by research: Older adults just can't get the sleep they need, taking longer to nod off, spending less time in deep sleep, and having more trouble staying asleep. In fact, more than half of men and women over the age of 65 say they suffer from at least one sleep problem, with many experiencing insomnia, according to WebMD.

Become more distracted

If you have trouble tuning out extraneous information, from background chatter to flashing billboards, age might not be your friend. As a person gets older, their ability to ignore distractions gets worse, according to Karen Campbell, a doctoral student in psychology at the University of Toronto. But Campbell and her colleagues found a silver lining that might focus you: Seniors might have the unique ability to "hyper-bind" the irrelevant information, tying it to other information appearing at the same time. The ability could ultimately boost memory.

Everything starts to sag

Your skin can be a dead giveaway that you've passed the half-century mark. With aging, the skin's outer layer, called the epidermis, thins. At the same time, the skin becomes less elastic and facial fat in the deeper layers of the skin wanes. The result: a loose, saggy façade marked by lines and crevices.

While injections of fillers can help plump up a face, researchers are now finding such cosmetic procedures might not be enough.

That's because jaw, cheek and eye-socket bones also wear down with the march of time, according to research led by Dr. Robert Shaw, Jr., of the University of Rochester. The loss of this "scaffolding" results in upper eyelid droop, plummeting cheeks and jowls that sway in the breeze. The study researchers suggest bone implants might be in order, though as with any surgery there are risks, such as infection and numbness.

Still enjoy a good laugh

Laughing is good for you, science has shown. That's good news for older adults who still appreciate humor - providing they understand it, according to a Canadian study published in a 2003 issue of the Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society.

"The good news is that aging does not affect emotional responses to humor - we'll still enjoy a good laugh when we get the joke," Prathiba Shammi, a psychologist with Baycrest Center for Geriatric Care, said in a statement. "This preserved affective responsiveness is important because it is integral to social interaction and it has long been postulated that humor may enhance quality of life, assist in stress management, and help us cope with the stresses of aging."

The downside of the study: Older adults had more trouble than spring chickens comprehending humor. They were less able to choose appropriate punch lines for jokes or to select the correct funny cartoon from an array of cartoons. Another research team came to the same conclusions in 2007, that older adults have a harder time "getting a joke" than younger individuals.

Have a positive attitude

The stereotypical picture of grumpy old men might not hold weight in science. Age could bring happiness for many people, though whether or not that conclusion is true and the reasons for cheerfulness in old age are debatable.

For instance, a study published in 2008 by Yang Yang, a sociologist at the University of Chicago, suggests the increase in lifespan that’s occurred since the 1970s has been linked with an increase in years of happiness. At the same time, however, health and income – important factors when it comes to happiness – decline with age. Some researchers have pointed out that when you take these two factors into account, the elderly are less happy than their younger counterparts.

Even so, whether well-being stays strong in old age could come down to a person's attitude. Research has shown older adults remember the past through a rose-colored lens; they are more optimistic than younger individuals; and the sick and disabled are just as happy as the rest of us.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.