Criminal Minds Are Different From Yours, Brain Scans Reveal

The latest neuroscience research is presenting intriguing evidence that the brains of certain kinds of criminals are different from those of the rest of the population.

While these findings could improve our understanding of criminal behavior, they also raise moral quandaries about whether and how society should use this knowledge to combat crime.

The criminal mind

In one recent study, scientists examined 21 people with antisocial personality disorder – a condition that characterizes many convicted criminals. Those with the disorder "typically have no regard for right and wrong. They may often violate the law and the rights of others," according to the Mayo Clinic.

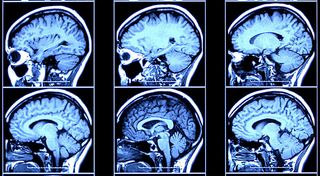

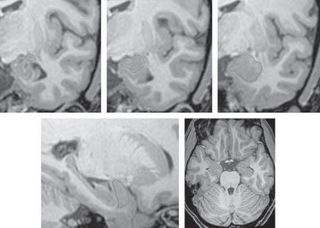

Brain scans of the antisocial people, compared with a control group of individuals without any mental disorders, showed on average an 18-percent reduction in the volume of the brain's middle frontal gyrus, and a 9 percent reduction in the volume of the orbital frontal gyrus – two sections in the brain's frontal lobe.

Another brain study, published in the September 2009 Archives of General Psychiatry, compared 27 psychopaths — people with severe antisocial personality disorder — to 32 non-psychopaths. In the psychopaths, the researchers observed deformations in another part of the brain called the amygdala, with the psychopaths showing a thinning of the outer layer of that region called the cortex and, on average, an 18-percent volume reduction in this part of brain.

"The amygdala is the seat of emotion. Psychopaths lack emotion. They lack empathy, remorse, guilt," said research team member Adrian Raine, chair of the Department of Criminology at the University of Pennsylvania, at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington, D.C., last month.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In addition to brain differences, people who end up being convicted for crimes often show behavioral differences compared with the rest of the population. One long-term study that Raine participated in followed 1,795 children born in two towns from ages 3 to 23. The study measured many aspects of these individuals' growth and development, and found that 137 became criminal offenders.

One test on the participants at age 3 measured their response to fear – called fear conditioning – by associating a stimulus, such as a tone, with a punishment like an electric shock, and then measuring people's involuntary physical responses through the skin upon hearing the tone.

In this case, the researchers found a distinct lack of fear conditioning in the 3-year-olds who would later become criminals. These findings were published in the January 2010 issue of the American Journal of Psychiatry.

Neurological base of crime

Overall, these studies and many more like them paint a picture of significant biological differences between people who commit serious crimes and people who do not. While not all people with antisocial personality disorder — or even all psychopaths — end up breaking the law, and not all criminals meet the criteria for these disorders, there is a marked correlation.

"There is a neuroscience basis in part to the cause of crime," Raine said.

What's more, as the study of 3-year-olds and other research have shown, many of these brain differences can be measured early on in life, long before a person might develop into actual psychopathic tendencies or commit a crime.

Criminologist Nathalie Fontaine of Indiana University studies the tendency toward being callous and unemotional (CU) in children between 7 and 12 years old. Children with these traits have been shown to have a higher risk of becoming psychopaths as adults.

"We're not suggesting that some children are psychopaths, but CU traits can be used to identify a subgroup of children who are at risk," Fontaine said.

Yet her research showed that these traits aren't fixed, and can change in children as they grow. So if psychologists identify children with these risk factors early on, it may not be too late.

"We can still help them," Fontaine said. "We can implement intervention to support and help children and their families, and we should."

Neuroscientists' understanding of the plasticity, or flexibility, of the brain called neurogenesis supports the idea that many of these brain differences are not fixed. [10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain]

"Brain research is showing us that neurogenesis can occur even into adulthood," said psychologist Patricia Brennan of Emory University in Atlanta. "Biology isn’t destiny. There are many, many places you can intervene along that developmental pathway to change what's happening in these children."

Furthermore, criminal behavior is certainly not a fixed behavior.

Psychologist Dustin Pardini of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center found that about four out of five kids who are delinquents as children do not continue to offend in adulthood.

Pardini has been researching the potential brain differences between people with a past criminal record who have stopped committing crimes, and those who continue criminal behavior. While both groups showed brain differences compared with non-criminals in the study, Pardini and his colleagues uncovered few brain differences between chronic offenders and so-called remitting offenders.

"Both groups showed similar results," Pardini said. "None of these brain regions distinguish chronic and remitting offenders."

Ethical quandaries

Yet even the idea of intervening to help children at risk of becoming criminals is ethically fraught.

"Do we put children in compulsory treatment when we've uncovered the risk factors?" asked Raine. "Well, who decides that? Will the state mandate compulsory residential treatment?"

What if surgical treatment methods are advanced, and there is an option to operate on children or adults with these brain risk factors? Many experts are extremely hesitant to advocate such an invasive and risky brain intervention — especially in children and in individuals who have not yet committed any crime.

Yet psychologists say such solutions are not the only way to intervene.

"You don’t have to do direct brain surgery to change the way the brain functions," Brennan said. "You can do social interventions to change that."

Fontaine's studies, for example, suggest that kids who display callous and unemotional traits don't respond as well to traditional parenting and punishment methods such as time-outs. Instead of punishing bad behavior, programs that emphasize rewarding good behavior with positive reinforcement seem to work better.

Raine and his colleagues are also testing whether children who take supplemental pills of omega-3 fatty acids — also known as fish oil — can show improvement. Because this nutrient is thought to be used in cell growth, neuroscientists suspect it can help brain cells grow larger, increase the size of axons (the part of neurons that conducts electrical impulses), and regulate brain cell function.

"We are brain scanning children before and after treatment with omega-3," Raine said. "We are studying kids to see if it can reduce aggressive behavior and improve impaired brain areas. It's a biological treatment, but it's a relatively benign treatment that most people would accept."

'Slippery slope to Armageddon'

The field of neurocriminology also raises other philosophical quandaries, such as the question of whether revealing the role of brain abnormalities in crime reduces a person's responsibility for his or her own actions.

"Psychopaths know right and wrong cognitively, but don't have a feeling for what's right and wrong," Raine said. "Did they ask to have an amygdala that wasn't as well functioning as other individuals'? Should we be punishing psychopaths as harshly as we do?"

Because the brain of a psychopath is compromised, Raine said, one could argue that they don't have full responsibility for their actions. That — in effect — it's not their fault.

In fact, that reasoning has been argued in a court of law. Raine recounted a case he consulted on, of a man named Herbert Weinstein who had killed his wife. Brain scans subsequently revealed a large cyst in the frontal cortex of Weinstein's brain, showing that his cognitive abilities were significantly compromised.

The scans were used to strike a plea bargain in which Weinstein's sentence was reduced to only 11 years in prison.

"Imaging was used to reduce his culpability, to reduce his responsibility," Raine said. "Yet is that not a slippery slope to Armageddon where there's no responsibility in society?"

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz.

Most Popular