Ancient Prickly Bugs Discovered

Paleontologists have identified a new species from 11 complete fossils of a slug-like creature covered with prickly armor that likely scooted along the ocean floor with a muscular foot more than 500 million years ago.

The finding sheds light on the evolutionary route to modern-day mollusks such as clams and squid.

The fossils were found in well-known fossil beds called the Burgess Shale, which are surrounded by mountains in British Columbia. These rock layers are a playground of sorts for fossil hunters as they are jam-packed with exceptionally preserved soft-bodied fossils from the Cambrian period, which lasted from 543 to 490 million years ago.

The newly described body-armored animals are rare and usually busted up in the fossil record, showing up as isolated pieces such as spines.

“Paleontologists have been frustrated for decades, finding these little shell-y parts without any idea of what it could be,” said Jean-Bernard Caron of the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Canada.

“So until you find a complete organism, you have absolutely no idea what those parts are. It’s like a Martian coming to our planet and finding a tiny bit of armor and wondering what it is. If the Martian finds a complete armor, he could say that was used for defense,” Caron told LiveScience.

Alien animal

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

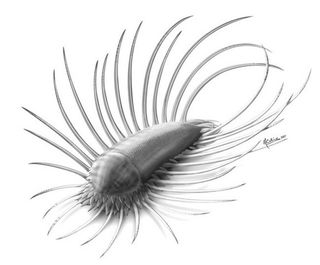

Called Orthrozanclus reburrus, the new animal was about half the size of a potato bug (called a garden pill bug by some) and had a front shell and long spines covering its entire body with a border of shorter spines along the edges [image]. Some of the spines were bent, suggesting they were not mineralized and instead consisted of chitin (like the horny, hard stuff that comprises lobster shells and bugs' exoskeletons). A mineralized material, like the organism’s shell, would have broken if bent.

Lacking any eyes or limbs, the creature likely scooted along the ocean bottom at a snail’s pace.

“We think it is an animal that was living at the bottom of the sea at the time, grazing on bacterial mats,” Caron said.

One of the specimens showed a faint impression of a gut, which the scientists speculate the organism filled with sediment from which it would filter out bacteria for food.

Family members

The hairy invertebrate (or organism lacking a backbone) shares features with two enigmatic animal groups called the halkieriids and the wiwaxiids. The evolutionary relationships between these two groups had been uncertain.

The halkieriids and wiwaxiids are members of a large group of animals called the lophotrochozoa, which includes mollusks, worms, and brachiopods, and figured heavily in the so-called Cambrian explosion. This span of about 30 million years is manifested in the fossil record with the sudden appearance of many groups of animals which gave rise to animals present today. Before the Cambrian period, the fossil record is devoid of any precursors to today's animal groups other than microbes.

Now with the new slug-like fossil discovery [image], the scientists suggest Orthrozanclus, halkieriids and wiwaxiids form their own group, which Caron and his colleague have dubbed the halwaxiids. So rather than giving rise to the mollusks, the organisms were a separate branch on the tree of life.

“We have a group of organisms that could have become a phyla today but never did, a group that shared characteristics with mollusk but was not a mollusk,” Caron said. “The group was basically an intermediate between mollusks and polycheate worms.”

The finding, reported in a research article published in the March 2 issue of the journal Science, suggests mollusks had already diverged before the evolution of the halwaxiids.

- Images: Small Sea Monsters

- Video: Shrimp on a Treadmill

- Top 10 Amazing Animal Abilities

- Images: Dino Fossils

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Most Popular