Hyperactive Comet Is a Spiky Mystery for Astronomers

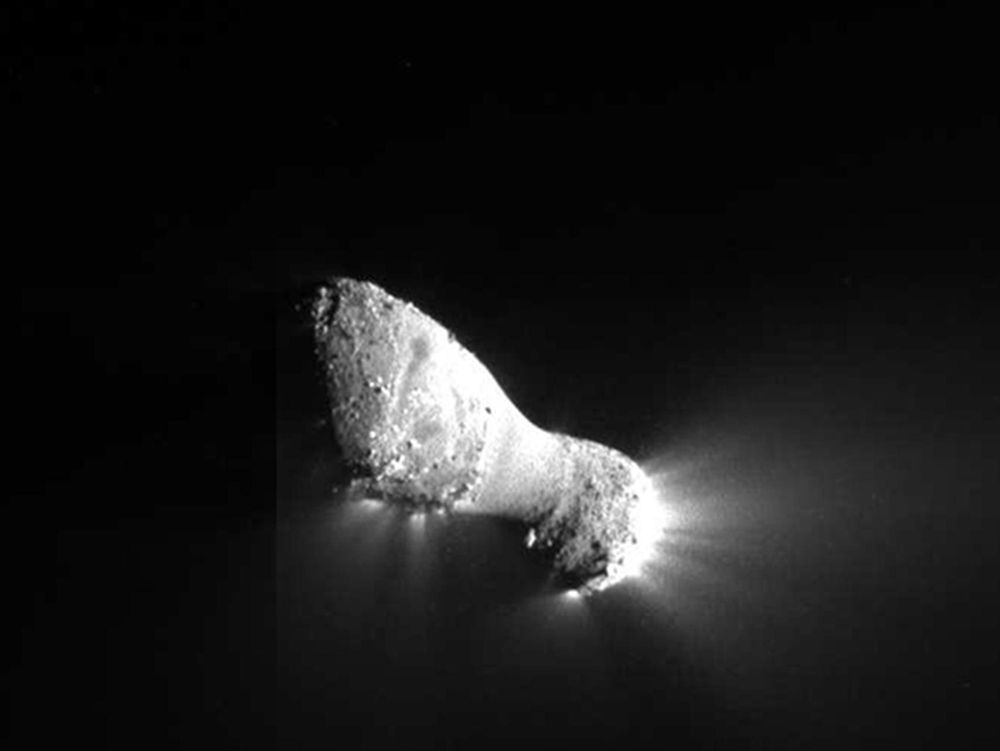

HOUSTON – Comet Hartley 2, the icy "space drumstick" photographed by NASA's Deep Impact spacecraft last year, is an active object that still perplexes scientists as it travels through the solar system.

Deep Impact visited Hartley 2 in November, revealing what one scientist described as "our favorite little hyperactive small comet."

Hartley 2 rotates around a central axis much as Earth does, scientists have revealed. But the comet also rolls around its long axis like a spinning bowling pin. Make that a spiky bowling pin: The rough edges of Hartley 2's surface are dotted with rocky spires that can reach 230 feet (70 meters) high.

The new details about comet Hartley 2 were unveiled last week at the 42nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in The Woodlands, Texas. [Photos of Comet Hartley 2 Up Close]

Hartley 2 spews out more water than other comets its size, said Michael A'Hearn, a University of Maryland astronomer and the principal investigator on the flyby mission. Frozen carbon dioxide deep in the comet's body turns to gas, jetting off the comet and dragging water with it.

"There are at least a dozen other comets for which we know that they're relatively high in activity for nucleus size, and they're probably driven either by carbon dioxide or carbon monoxide," A'Hearn told SPACE.com. "What we don't know yet it whether these are a separate class or whether they're just a continuum extending from these more 'normal' comets."

Spiky bowling pin

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Deep Impact flew to within 435 miles (700 kilometers) of Hartley 2 on Nov. 4, 2010, just a few weeks after the comet had passed within 11 million miles (17.7 million km) of Earth. Within hours, the craft, which is equipped with two cameras and a near-infrared spectrometer, began beaming back about 125,000 images of the comet, which has two rough, knobby ends and a smooth "waist."

Researchers aren't sure whether the two rough sides of Hartley 2 are connected by solid rock. At least the outer layer – which is several tens of meters thick – is a sort of loose aggregate of material that sloughed off the comet and gathered there, A'Hearn said. [Video: Comet Hartley 2 Visit by Deep Impact]

The rough ends of Hartley 2 are dotted with spires and rocky blocks, said Cornell University geomorphologist Peter Thomas, who analyzed the terrain of the comet.

And although the comet is constantly throwing off particles as it nears the sun, it lacks the pits and holes seen in other comets. In fact, some parts of Hartley 2, including the spires, seem to get built up before collapsing.

"We've got an environment of material being moved around on the surface, a sedimentary environment in an object that is losing mass," Thomas said.

Rough edges

Hartley 2 throws off pure, fine-grained ice crystals, aggregated in fluffy chunks as big as basketballs. But what you see coming off the comet depends on where you look, said Lori Feaga, an assistant research scientist at the University of Maryland. The smooth waist puts out more water than the knobby ends, which seem to specialize in outgassing carbon dioxide.

"For the first time, we are able to show that sublimation of subsurface CO? is actually driving the outgassing activity on a cometary nucleus," Feaga said, "and that the emission is directly linked to the [type of] surface."

Because comets are leftovers from the formation of the solar system, the differences in gas composition between regions of Hartley 2 have led to speculation that the two nodes of the comet formed in separate areas of the solar system.

"We would love to conclude that," A'Hearn said. But the team will need to analyze more data before it can make any claims about the comet's formation, he said

"We hope to be able to do that within six months or so," A'Hearn said.

Stephanie Pappas is a senior writer with LiveScience. You can follow her on Twitter @sipappas.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.