4.5-Billion-Year-Old Antarctic Meteorite Yields New Mineral

A meteorite discovered in Antarctica in 1969 has just divulged a modern secret: a new mineral, now called Wassonite.

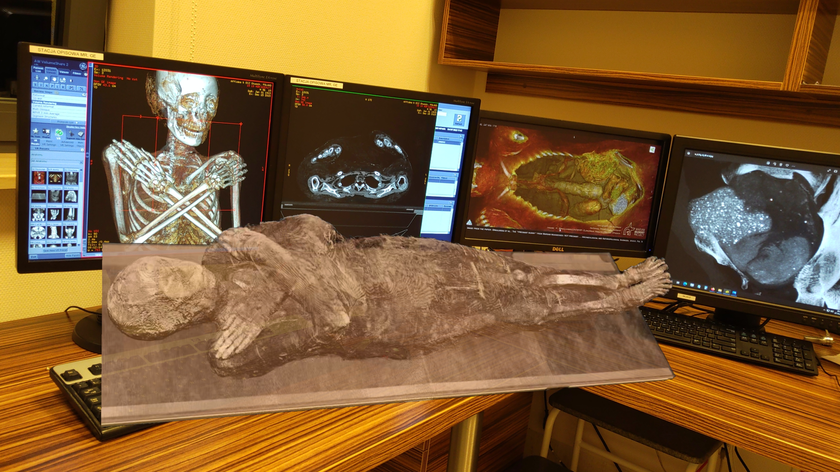

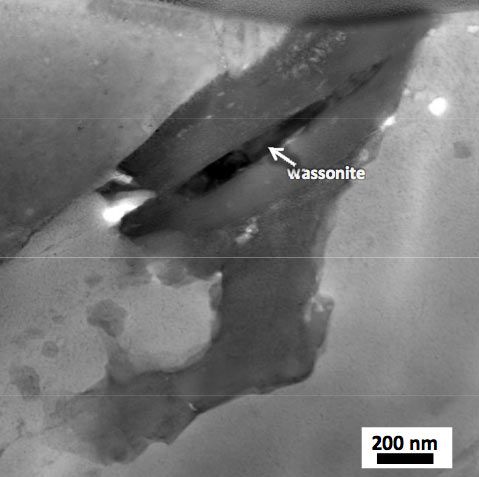

The new mineral found in the 4.5-billion-year-old meteorite was tiny — less than one-hundredth as wide as a human hair. Still, that was enough to excite the researchers who announced the discovery Tuesday (April 5). [Image of new mineral]

"Wassonite is a mineral formed from only two elements, sulfur and titanium, yet it possesses a unique crystal structure that has not been previously observed in nature," NASA space scientist Keiko Nakamura-Messenger said in a statement.

The mineral's name, approved by the International Mineralogical Association, honors John T. Wasson, a UCLA professor known for his achievements across a broad swath of meteorite and impact research.

Grains of Wassonite were analyzed from the meteorite that has been officially designated Yamato 691 enstatite chondrite. Chondrites are primitive meteorites that scientists think were remnants shed from the original building blocks of planets. Most meteorites found on Earth fit into this group.

Yamato 691 likely originated from an asteroid orbiting between Mars and Jupiter. It was discovered along with eight other meteorites by members of the Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition on the blue ice field of the Yamato Mountains. They constituted the first significant recovery of Antarctic meteorites. Follow-up searches by scientists from Japan and the United States have recovered more than 40,000 specimens, including rare Martian and lunar meteorites.

The research team used NASA's transmission electron microscope to isolate the Wassonite grains and figure out their chemical makeup and atomic structure.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When meteors hit the ground they are called meteorites. Most are fragments of asteroids (space rocks that travel through the solar system), and others are mere cosmic dust shed by comets. Rare meteorites are impact debris from the surfaces of the moon and Mars. "Meteorites, and the minerals within them, are windows to the formation of our solar system," said co-discoverer Lindsay Keller, space scientist at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston. "Through these kinds of studies we can learn about the conditions that existed and the processes that were occurring then."

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.