Bones of Leper Warrior Found in Medieval Cemetery

The bones of a soldier with leprosy who may have died in battle have been found in a medieval Italian cemetery, along with skeletons of men who survived blows to the head with battle-axes and maces.

Studying ancient leprosy, which is caused by a bacterial infection, may help scientists figure out how the infectious disease evolved.

The find also reveals the warlike ways of the semi-nomadic people who lived in the area between the sixth and eighth centuries, said study researcher Mauro Rubini, an anthropologist at Foggia University in Italy. The war wounds, which showed evidence of surgical intervention, provide a peek into the medical capabilities of medieval inhabitants of Italy.

"They knew well the art of war and also the art of treating war wounds," Rubini told LiveScience.

Buried horses and bashed-in skulls

The cemetery of Campochiaro is near the central Italian town of Campobasso. Between the years 500 and 700, when the cemetery was in use, Rubini said, the area was under the control of the Lombards, a Germanic people who allied with the Avars, an ethnically diverse group of Mongols, Bulgars and Turks. No signs of a stable settlement have been found near Campochiaro, Rubini said, so the cemetery was likely used by a military outpost of Lombards and Avars, guarding against invasion from the Byzantine people to the south.

So far, Rubini said, 234 graves have been excavated, many containing both human and horse remains. Burying a man with his horse is a tradition that hails from Siberia, Mongolia and some Central Asian regions, Rubini said, suggesting that the Avars brought their death rituals with them to Italy.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

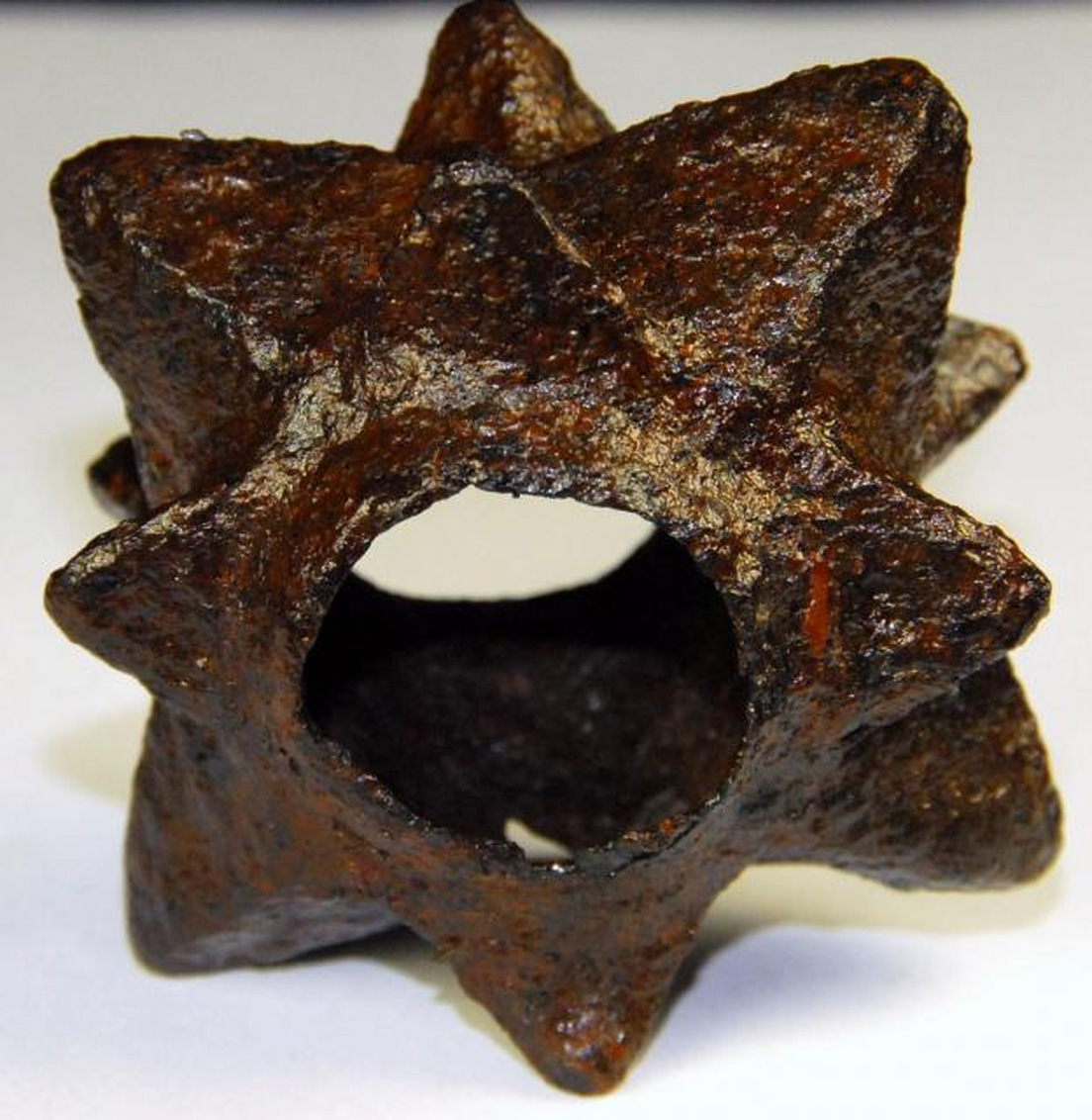

Rubini and his colleague Paola Zaio detailed three of these bodies in an article to be published in the Journal of Archaeological Science. The first man was about 55 when he died, the researchers found. They aren't sure what killed him, but they do know what he managed to survive: a blow to the head that tore a 2 inch (6 centimeter) hole in his skull. The pattern of the wound and the size of the hole suggest a Byzantine mace as the weapon, Rubini said.

Almost as alarming, the man probably went through the medieval equivalent of brain surgery. The margins of the wound are smooth and free of fragments, Rubini said.

"Probably the margins were polished with an abrasive instrument," he said.

Whatever happened, the man survived his wound. The bone had begun to heal and grow before the man died, Rubini said.

A leper warrior?

Body No. 2, another man of 50 or 55, painted a similar forensic picture. Judging by the shape of the wedge-shaped dent in the man's skull, Rubini said, he probably got in the way of a Byzantinian battle-ax. Like his comrade with the hole in the head, this man survived for a long time after he was wounded.

The third soldier wasn't so fortunate, the researchers suspect. First of all, his bones show the telltale wasting and mutilation of leprosy, now known as Hansen's disease. In ancient times, leprosy sufferers were often banished from society. Apparently the Lombards and Avars took a more tolerant approach, Rubini said, because this man, who died around age 50, was buried in the cemetery along with the other dead. [Read: Earliest Known Case of Leprosy Unearthed]

The leprosy sufferer's skull bears the mark of what Rubini and Zaio indentify as a sword slash. It may not have killed him, but the wound shows no signs of healing, suggesting the man died within hours of sustaining it.

"The Avar society was very inflexible militarily, and in particular situations all are called to contribute to the cause of survival, healthy and sick," Rubini said. "Probably this individual was really a leper warrior who died in combat to defend his people against the Byzantinian soldiers."

Whoever he was, the mysterious leper may help researchers understand how the disease evolved over time. Rubini and other researchers are working to extract the DNA of the bacteria that causes leprosy from bones found in the cemetery. The goal is to compare the medieval version of the disease to the bacteria alive today, Rubini said: "We study the past to know the present."

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.