New Recordings of 'Extinct' Ivory-Billed Woodpecker

Every morning, Michael Collins heads to the Pearl River bayou near his Louisiana home to bird-watch for a couple of hours before work. He gets around the swamp by kayak, hauling cameras, tape recorders, and tree climbing ropes through the swamp, and searches, day after day, for the holy grail of birds – a species that no one is sure even still exists. Every so often – once or twice a year, on average – his perseverance is rewarded: He catches a fleeting glimpse of an ivory-billed woodpecker.

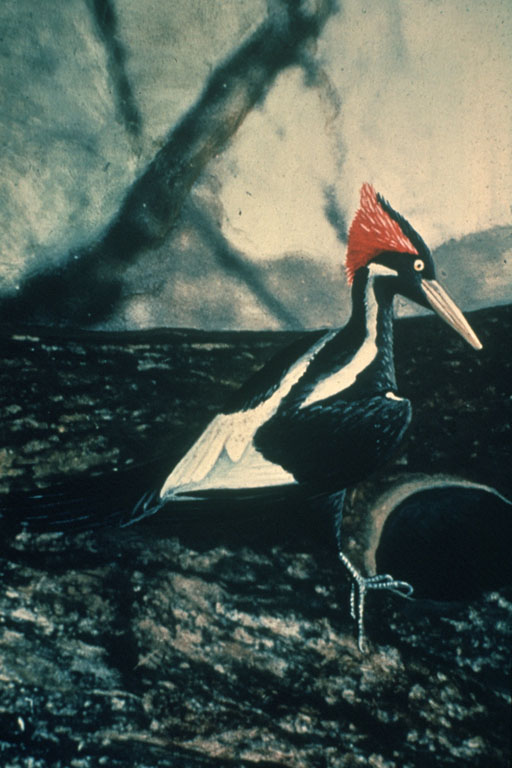

And this is a remarkable thing, as no one is certain that the ivory-billed woodpecker, the so-called "Lord God bird," still lives. It was hunted to the brink of extinction in the 1930s, and for 60 years most ornithologists thought the bird, the largest woodpecker in the United States, and which John James Audubon described as "graceful to the extreme," had fallen off the precipice forever.

Collins has seen the birds more often than any other human being. "I'm not going to dance around the issue. I've seen them. I've had 10 sightings; I've obtained three videos," Collins told Life's Little Mysteries.

If he sounds defensive, well, he is. Collins is an outsider to the ornithology community—he's just a hobbyist bird-watcher—and few insiders take his work seriously. His evidence has been rejected by a string of ornithology journals – often, he says, without explanation.

And so he has turned to acoustics scientists to confirm his recordings. This month he will finally publish what he believes is solid evidence that ivory-billed woodpeckers live at Pearl River in the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America.

Collins, a researcher at the Naval Research Laboratory-Stennis Space Center in Mississippi, first started searching for the bird when a team of Cornell ornithologists captured putative footage of a specimen in Arkansas in 2005. That possible sighting, the first well-documented (though not definitive) human encounter since about 1940, made it onto the cover of Science Magazine. The birds were said to have lived at Pearl River in the past, so when Collins heard that they might still exist as a species, he decided to look for them there. [Why Don't Woodpeckers Get Headaches?]

He never could have known that doing so would cause him so much trouble.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Fast Flight and Double Knocks

Collins captured his best video and audio recordings from 75 feet off the ground. "The idea was to pick the tallest tree and get up above the tree tops so that I would be able to see the bird up to a quarter-mile away. But, amazingly, the bird actually flew underneath the tree I was in, along the bayou almost directly below," he said.

By analyzing the size of the bird relative to its surroundings in the video, he determined that its wingspan was approximately 30 inches – the historically recorded size of an ivory-billed woodpecker. Careful frame-by-frame measurements revealed a flight speed of 15.6 meters per second (35 mph) – approximately its purported speed, according to the historical record, and much faster than its relative the pileated woodpecker. Collins also analyzed the bird's coloring, and found that the pattern of white and black on its wings matched ivory-billed, not pileated.

The audio recordings, which he obtained in conjunction with the videos, also smack of the Lord God bird, which makes very distinct double knocks when pecking, and makes vocalizations somewhat like a blue jay's and nothing like a pileated woodpecker's. Collins used his mathematics expertise to construct sophisticated acoustical models of the bird's vocalizations. The audio and video evidence combined, he says, give firm support to his claim that ivory-billed woodpeckers live at Pearl River.

So why wasn't his research published in an ornithology journal?

Pros vs. amateurs

"Professional jealousy is a huge problem in the field of ornithology," Collins said. "There are groups who have received a lot of funding to obtain conclusive data on these birds and haven't managed to do so, and I've done it independently." One such group, he said, is the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, the country's leading center of ornithology research and the group who may have sighted the elusive woodpecker in 2005.

"The bird-watching community is also mixed up in the politics. It's important for the big name bird- watchers to be regarded as having exceptional skills and so on. But you have to go out and spend months to find these birds. It's very difficult and they don't want to pay the dues." Collins said he has paid said dues through tree climbing, kayaking, camera work and, most important, thousands of hours of observations.

The Cornell group, which Collins accuses of having exerted its influence to keep his work out of ornithology journals, commented briefly on his new acoustics paper. "Although we believe the evidence presented is inconclusive, we applaud Collins's continued efforts to locate and document possible ivory-billed woodpeckers and to publish his findings for all to evaluate," Kenneth Rosenberg, director of conservation science in the group, said.

Geoff Hill, an ornithologist at Auburn University who led a group that recently obtained tentative recordings of the ivory-billed woodpecker in Florida, had more to say about the new paper. "Mike [Collins] lays out good arguments. It certainly doesn't settle the issue — there's nothing definitive in what he presents — but it's an interesting case." He added, "Of course, whether something is 'definitive' is to some degree a matter of opinion." (Hill doesn't describe his own recordings of possible ivory-billed woodpeckers in Florida as 'definitive,' either.)

Hill said Collins's audio recordings of double-knock pecking sounds were particularly interesting as they wouldn't have been made by a pileated woodpecker. And while the sounds could have simply been a tree creaking in the wind or a duck flapping, the fact that they were obtained at the same time Collins made a positive visual identification of a woodpecker seems compelling.

When asked why Collins' work wasn't accepted by ornithology journals, Hill said it's because Collins isn't an ornithologist and so he doesn't know the terminology, and because "it's hard to get papers published. Over 50 percent of submitted papers get rejected."

Not yet a dodo

Hill, Collins and the Cornell group agree on one matter: they think the ivory-billed woodpecker is out there. "I think the birds do exist," Hill said, "they're just extremely hard to find. First, they live in some of the habitats in North America that are the most difficult for humans to deal with: swamp forest. Second is that these birds were shot to the very edge of extinction. There was never deforestation over the whole South; these birds were shot. So the birds that are left are extremely wary of people."

Collins thinks admitting they exist is key to helping them survive. "All these politics are very damaging. We should be saying, 'OK, the bird exists, it's just very difficult to observe. Now where are they? Where do they live? How can we save them?"

This story was provided by Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to LiveScience.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.