Global Warming or Little Ice Age: Which Will It Be?

Our sun may be on the verge of a relatively long snooze, as researchers have found solar energy output could decrease in the coming decades. Though the dip in solar activity isn't expected to reverse climate change and plunge Earth into a cold snap, similar phenomenon have happened in our planet's history, scientists say.

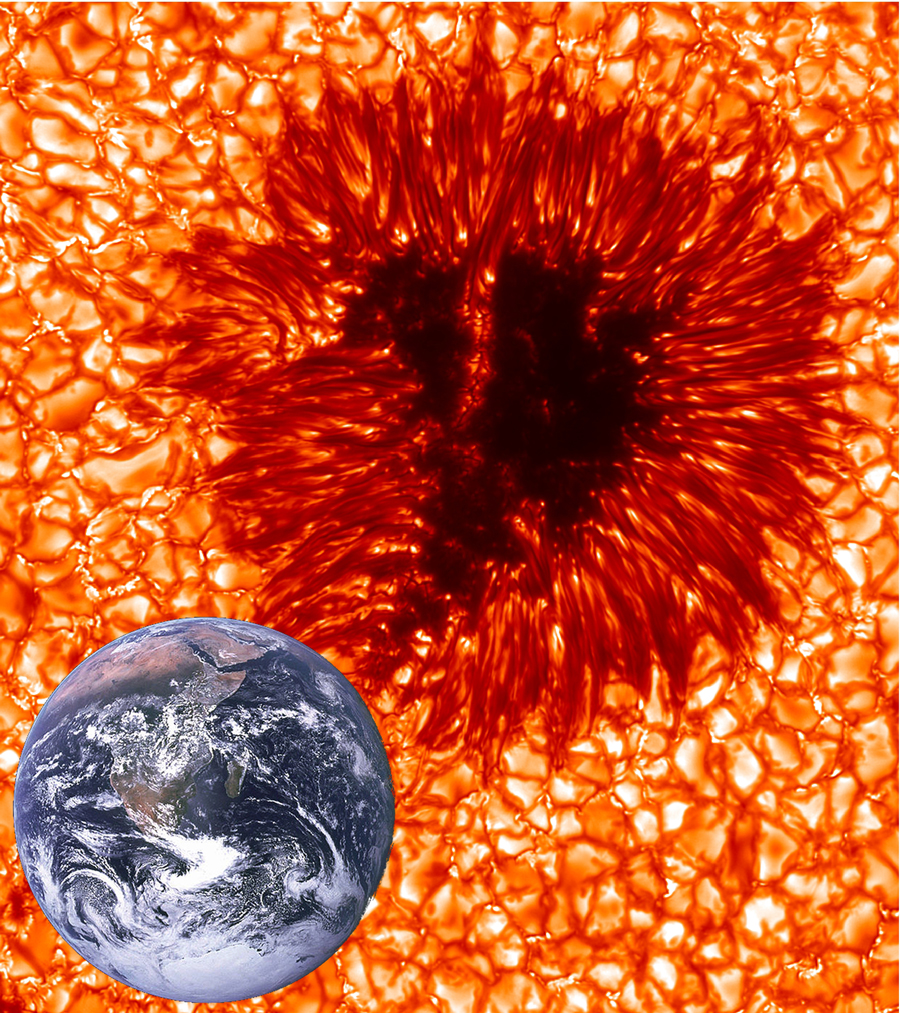

Some researchers say that changes in sun activity caused the "Little Ice Age" from 1500 to 1800 — during the chilliest part of this cooling trend beginning in 1645, the sun reached its 75-year Maunder Minimum, when astronomers found almost no sunspots. But the connection between solar activity and Earth's climate remains largely mysterious — scientists are not sure how much of a role the Maunder Minimum played in fueling the little ice age.

And despite media claims in recent days that global cooling is imminent, experts don't expect a repeat of the little ice age anytime soon.

"It turns out this would be a very minor impact on the climate, even if we were to return to Maunder Minimum conditions," climate scientist Michael Mann, of Pennsylvania State University, told LiveScience. "That would only lead to a decrease in about 0.2 watts of power per square meter of the Earth's surface — that compared to greenhouse forcing, which is more than 2 watts per meter squared. That's a factor of 10 larger." [The World's Weirdest Weather]

Predicting solar activity

When researchers refer to solar activity, they generally mean the number and intensity of sunspots, which are dark, cool, magnetically twisted areas on the sun that sometimes erupt violently and send streams of charged particles into space. This activity ebbs and flows in an 11-year cycle.

Even while approaching the next peak in the cycle, a typically storm period called solar maximum that's due in late 2013, the sun seems to be entering a decreased solar output phase, new research has suggested, one that might all but eliminate sunspot activity during the next cycle, which hits its maximum again in 2022. The data supporting this come from three separate analyses of sunspot activity, solar jet streams and the magnetic field.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I'm skeptical of all three pieces of evidence that were presented," said Doug Biesecker, of NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center, who notes that the data is based on only a few years of observations. "We know the sun doesn't behave exactly the same way all the time, so give the sun a chance to show its normal behavior before we say it's abnormal."

Fewer sunspots would mean lower sun activity in general, the researchers who presented the work believe; and they expect fewer of the suns' intense bright spots called faculae, which ring the sunspots. This decreased brightness would lower the amount of energy that reaches the Earth from the sun. But by how much is an open question.

A new Little Ice Age?

The Little Ice Age that began in the 1500s could have been caused by decreased solar output of just 0.2 percent, previous research by Peter Foukal suggests, though he believes that there were most likely other, earthly factors (including several erupting volcanoes) at play as well.

"If it really were true that the sun were to descend into a period of literally no sunspots for tens of years, there's a possibility that what occurred in the 17th century could occur again," Foukal, of HelioPhysics Inc., told LiveScience. "But we can't be sure there is a causal effect, we can't say for sure why it happened in the 17th century."

Foukal believes that the effect of a solar minimum could help mitigate some of the global warming we are experiencing, though he warns that eventually the minimum will end. "It could mitigate partially if the sun does cool things a little bit, but it's a matter of time before the sun comes back to life again [and] you will roast," Foukal told LiveScience.

Even if the sun has reached a new low point in its cycle, the change in solar output would not be nearly enough to undo even the current warming we've already experienced from increased greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere, Mann said.

Predicting solar output

Researchers have a tough time predicting changes in solar output, though scientists include in their climate simulations the little information they have about solar changes. The known 11-year-cycle is already built into their climate predictions, though it's difficult to know how active any given cycle will be.

A paper published last year by Georg Feulnerand Stefan Rahmstorf (of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Potsdam, Germany) in the journal Geophysical Research Letters tried to use these models to predict what would happen if the sun did actually enter a new Maunder Minimum starting in 2030. The model found the numbers that agreed with those quoted by Mann — a decrease of 0.2 watts of power per meter, which is the equivalent of 0.2 degree Fahrenheit (0.1 degree Celsius) of cooling.

"The influence of the grand solar minimum is to decrease the effect of the greenhouse gasses by a few tenths of a degree," Mann said about the results of that study. "How much of a player compared to other drivers that we know are important? It's almost down in the noise, it's a blip on the radar screen."

The sun and the Little Ice Age

While admitting that a small decrease in warming could happen, Mann doesn't agree that it could send Earth into another Little Ice Age. "It's ludicrous, there is no scientific support for that whatsoever," Mann said. "The science doesn't even remotely support that conclusion."

Mann believes that the temperature changes during the Little Ice Age were mainly caused by several volcanic eruptions during that time, which changed the temperatures and dynamics of the atmosphere, causing localized cooling.

Changes to the jet stream also affect local temperatures, as it moves cooler air upward across Europe. The jet stream is dependent on ozone levels in the atmosphere, which in turn can be affected by either solar radiation or by volcanic output in the atmosphere. The debate still rages as to how big of an effect each of these factors play.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus