Fossil Eyes Reveal Predator's Sharp Vision

Ancient animals saw the world through multi-faceted compound eyes, a new fossil discovery reveals. The ancient eyes, which date back half a billion years, probably belonged to a predator, likely a giant shrimp-like creature.

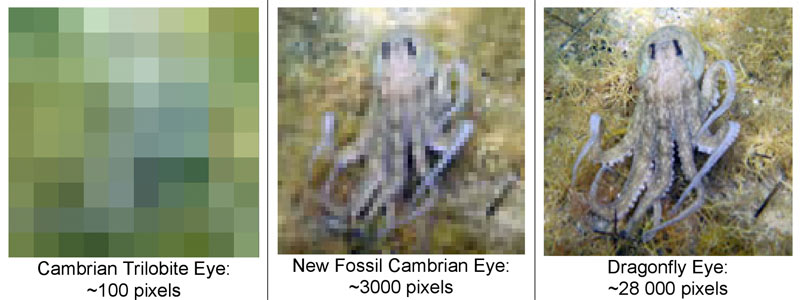

Like a modern fly, the ancient creature relied on compound eyes consisting of thousands of separate lenses to see the world. Each lens provides a pixel of vision. The more lenses, the better the creature could see. The mysterious ancient shrimp saw better than any other animal yet discovered from its era: Its eyes contained 3,000 lenses.

The fossil eyes were found by Australian researchers on Kangaroo Island, South Australia. They're 515 million years old, meaning the animal lived just after the "Cambrian Explosion," a sudden burst of life and diversity that began 540 million years ago.

"The new fossils reveal that some of the earliest arthropods had already acquired visual systems similar to those of living forms, underscoring the speed and magnitude of the evolutionary innovation that occured during the Cambrian Explosion," the authors wrote in the Nature article.

Because the eyes were found isolated, researchers can't say with certainty what sort of animal carried them. But the fossils were found in the same rock as an array of ancient marine animals, suggesting a creature something like what the world would have looked like to the ancient animal ]

Other animals from this timeframe had a mere 100 pixels of vision, the researchers reported today (June 29) in the journal Nature. With 3,000 pixels, the newly discovered ancient animals would have seen three times better than the modern horseshoe crab. But its eyesight would have paled in comparison to the modern dragonfly, which has 28,000 lenses in each eye.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.