A Lost World? Atlantis-Like Landscape Discovered

Buried deep beneath the sediment of the North Atlantic Ocean lies an ancient, lost landscape with furrows cut by rivers and peaks that once belonged to mountains. Geologists recently discovered this roughly 56-million-year-old landscape using data gathered for oil companies.

"It looks for all the world like a map of a bit of a country onshore," said Nicky White, the senior researcher. "It is like an ancient fossil landscape preserved 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) beneath the seabed."

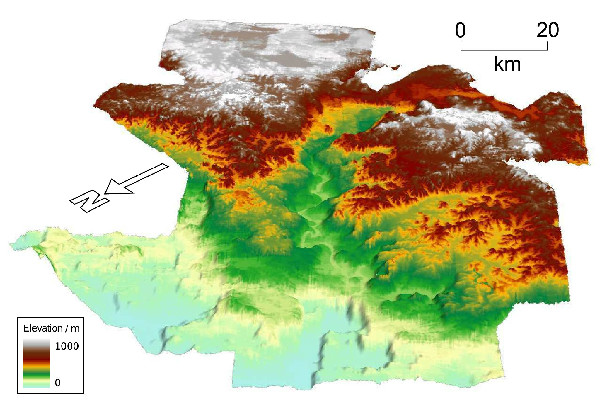

So far, the data have revealed a landscape about 3,861 square miles (10,000 square km) west of the Orkney-Shetland Islands that stretched above sea level by almost as much as 0.6 miles (1 km). White and colleagues suspect it is part of a larger region that merged with what is now Scotland and may have extended toward Norway in a hot, prehuman world.

History beneath the seafloor

The discovery emerged from data collected by a seismic contracting company using an advanced echo-sounding technique. High pressured air is released from metal cylinders, producing sound waves that travel to the ocean floor and beneath it, through layers of sediment. Every time these sound waves encounter a change in the material through which they are traveling, say, from mudstone to sandstone, an echo bounces back. Microphones trailing behind the ship on cables record these echoes, and the information they contain can be used to construct three-dimensional images of the sedimentary rock below, explained White, a geologist at the University of Cambridge in Britain.

The team, led by Ross Hartley, a graduate student at the University of Cambridge, found a wrinkly layer 1.2 miles (2 km) beneath the seafloor — evidence of the buried landscape, reminiscent of the mythical lost Atlantis.

The researchers traced eight major rivers, and core samples, taken from the rock beneath the ocean floor, revealed pollen and coal, evidence of land-dwelling life. But above and below these deposits, they found evidence of a marine environment, including tiny fossils, indicating the land rose above the sea and then subsided — "like a terrestrial sandwich with marine bread," White said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The burning scientific question, according to White, is what made this landscape rise up, then subside within 2.5 million years? "From a geological perspective, that is a very short period of time," he said.

The giant hot ripple

He and colleagues have a theory pointing to an upwelling of material through the Earth's mantle beneath the North Atlantic Ocean called the Icelandic Plume. (The plume is centered under Iceland.)

The plume works like a pipe carrying hot magma from deep within the Earth to right below the surface, where it spreads out like a giant mushroom, according to White. Sometimes the material is unusually hot, and it spreads out in a giant hot ripple.

The researchers believe that such a giant hot ripple pushed the lost landscape above the North Atlantic, then as the ripple passed, the land fell back beneath the ocean.

This theory is supported by other new research showing that the chemical composition of rocks in the V-shaped ridges on the ocean floor around Iceland contains a record of hot magma surges like this one. Although this study, led by Heather Poore, also one of White's students, looked back only about 30 million years, White said he is hopeful ongoing research will pinpoint an older ridge that recorded this particular hot ripple.

Because similar processes have occurred elsewhere on the planet, there are likely many other lost landscapes like this one. Since this study was completed, the researchers have found two more recent, but less spectacular, submerged landscapes above the first one, White said.

Both studies appear today (July 10) in the journal Nature Geoscience.

You can follow LiveScience writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.