Giant Rat Kills Predators with Poisonous Hair

By utilizing the same plants that African tribesmen use to poison their arrows, the furry fury known as the African crested rat can incapacitate and even kill predators many times its size, researchers have found.

"This is the first mammal that is borrowing a deadly poison from a plant and slathering it on itself without dying," said study researcher Jonathan Kingdon, of Oxford University in England. "This is an extraordinary thing to have evolved."

Growing up in Africa, Kingdon was frequently exposed to these rats, even keeping one (very cautiously) as a pet. He had heard this animal was poisonous, but it took 30 years for him to figure out how and why this special animal kills and sickens its predators. [Top 10 Deadliest Animals]

Hair-raising situation

Whenever a predator, like a dog, comes upon the rat and tries to eat it, the animal gets a mouthful of potentially deadly poison.

"It isn't really designed to kill. If it killed every time nothing would ever learn that this is distasteful," Kingdon said. "The way it really works is that you go away and you recover from a terrible experience and you never, ever invite that experience again."

Kingdon noted one example he's seen firsthand: When in the presence of a crested rat, a dog that previously had a run-in with one of the animals quivered in fear and wouldn't approach the innocuous- looking foot-long rat.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Evolutionary marvel

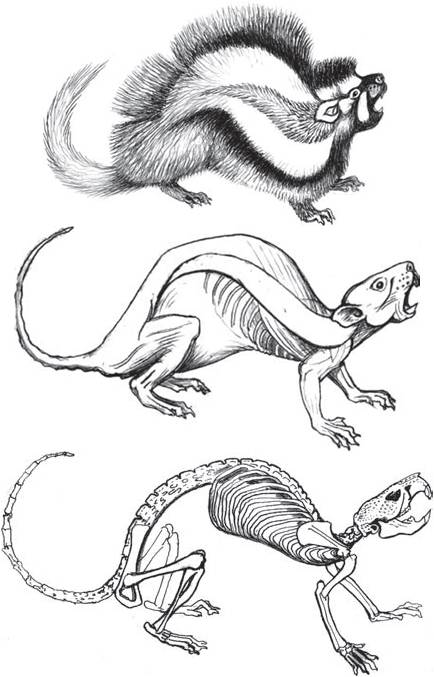

To figure out the rat's secret, Kingdon and his colleagues observed the rats in the wild and ran lab tests on a line of hairs that run along its back and seemed to have a unique structure. They also tested the chemicals in the hairs' poisons alongside that of the bark of the Acokanthera schimperi, which the rats are known to chew.

They found that to make its poison fur, the rat — which averages about 14 inches (36 cm) long — chews the bark of the A. schimperi and licks itself to store the resulting poisonous spit in specially adapted hairs. This behavior is hardwired into the animal's brain, similar to nitpicking behavior of birds or self-bathing of cats, the researchers suspect.

"What is quite clear in this animal is that it is hardwired to find the poison, it is hardwired to chew it and it is hardwired to apply it to the small area of hairs," Kingdon said. The animals apply the poisonous spit only to the specialized hairs on a small strip along its back. When threatened, the rat arches its back and uses specially adapted muscles to slick back its hair and expose the strip of poison. [Image of giant rat ]

Poison from this tree bark has been used by hunters to take down large prey, like elephants, for thousands of years. "Evolution has mimicked something that hunters do," Kingdon said. "It [the crested rat] is borrowing from the plant just as the hunters are borrowing from the very same plant."

Medical miracle

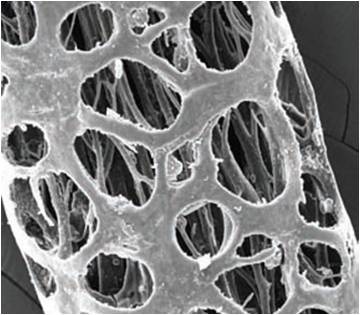

The hairs themselves are specially structured to absorb the poison, Kingdon found. Their outer layer is full of large holes, like a pasta strainer, and the inside is full of straight fibers that wick up liquids. "There is no other hair that is known to science that is remotely structured like these hairs," Kingdon said.

It is unknown why the rat doesn't die from chewing the poison, though it could be resistant somehow. "The rats should drop dead every time they chew this stuff but they are not," Kingdon said. "We don't have the slightest idea how that could be done."

Learning more about how this poison works could even help human medicine, since it acts by inducing heart attacks. A related chemical, called digitoxin, has been used for decades as a treatment for heart failure.

The study was published today (Aug. 2) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.