Ice World: Gallery of Awe-Inspiring Glaciers

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Mountains of Ice

Although they've been on the retreat since Earth's last ice age, glaciers still have the power to amaze. These frozen masses of ice cover 10 percent of Earth's land area, appearing on every continent, even Africa, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC). Here are a few notables. (Above, glacial ice at Parque Nacional los Glaciares in Argentina.)

Aletsch Glacier, Switzerland

The largest and longest glacier in Europe snakes among mountain peaks like a river frozen in time. Glaciers form when layers of snow build upon one another year after year. Eventually, the lower layers re-crystallize into ice. Tiny air bubbles in the ice preserve bits of ancient atmosphere, making glaciers an important research tool for scientists looking to understand the climate of thousands of years ago.

Ice Fields of Kilimanjaro

Snow-covered glaciers on the summit of Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania. Unfortunately, Kilimanjaro glaciers are retreating rapidly in recent years, according to research published in November 2009 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Between 1912 and 1953, the mountain's ice cover shrank by about 1 percent each year. Between 1989 and 2007, that rate increased to 2.5 percent per year.

Briksdal Glacier

The Briksdal Glacier in Norway. According to NSIDC, glacial ice gets its blue color when it becomes very dense. White-colored glacial ice has many tiny air bubbles embedded amidst its ice crystals. As the ice becomes dense, those air bubbles get forced out. The ice that is left behind absorbs all colors in the ice spectrum except blue.

Glacial Tunnel

An ice cave or englacial melt channel. This ice cave was formed by meltwater flowing within the glacier ice. Belcher Glacier, Devon Island, Nunavut, Canada.

Cold Camp

A mountain-climbing expedition makes camp on a glacier on the slopes of Mount Elbrus, an inactive volcano in the Caucasus mountains of Russia.

Breiðamerkurjökull

Iceland is known for its glaciers with tongue-twisting names. Breiðamerkurjökull is in the southeastern part of the country.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Blue Lagoon

Breiðamerkurjökull terminates at Jökulsárlón, the largest glacial lagoon in Iceland. The glacier expanded between the 1600s and the 1900s, during a cold period known as "The Little Ice Age." Warming temperatures since sent the glacier into retreat. Starting in about 1935, Jökulsárlón began to form in its wake. The glacial lagoon is now about 650 feet (200 meters) deep where the glacier's nose once was.

Fog & Ice

Fog crosses Hailuoguo glacier on Mount Gongga in the Sichuan province of China.

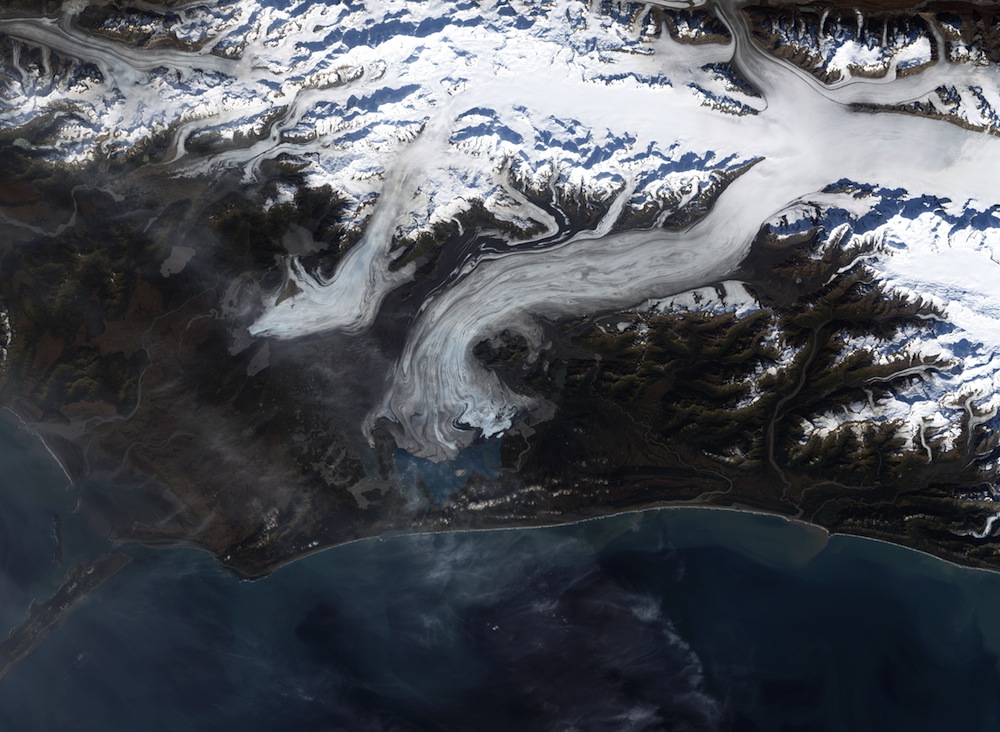

Alaskan Ice

An aerial view of the Kennicott and Rott glaciers in the Wrangell Mountains of Alaska. Most of the United States' glaciers are located in Alaska.

Bering Up

The largest glacier in North America is Alaska's Bering Glacier, which currently terminates in the Vitus Lake about 6 miles (10 km) from the Gulf of Alaska.

The retreat of the Bering glacier, which has been ongoing since 1900, has the side effect of increasing the number of earthquakes in the area. The weight of the glacier once stabilized the boundary between the Pacific and North American tectonic plates, which meet along the Alaska coast. As the ice retreated, that compression disappeared, enabling the two plates to move against one another more freely.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus