How to Win at Rock, Paper, Scissors

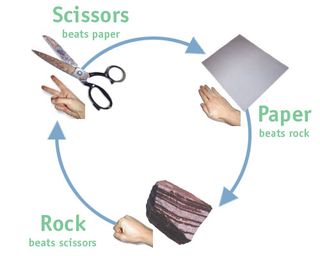

In the game Rock, Paper, Scissors, two opponents randomly toss out hand gestures, and each one wins, loses or draws with equal probability. It's supposed to be a game of pure luck, not skill — and indeed, if humans were able to be perfectly random, no one could gain an upper hand over anyone else.

There's one problem with that reasoning: Humans are terrible at being random.

Our pathetic attempts to appear uncalculating are, in fact, highly predictable. A couple of recent studies have provided insights into the patterns by which people tend to play Rock, Paper, Scissors (and why). Abide by them, and you'll be riding shotgun and eating the bigger half of the cookie for the rest of your life.

According to Graham Walker, veteran player and five time organizer of the World Rock, Paper Scissors Championships, there are two paths to victory in RPS: Eliminating one of your opponent's options — for example, influencing her not to play Paper — and forcing her to make a predictable move. In both cases, Walker wrote on the website of the World RPS Society, "the key is that it has to be done without them realizing that you are manipulating them."

Rookies rock

Those two overarching strategies can be translated into executable moves, starting with the opening one. Expert players have observed that inexperienced ones tend to lead with Rock. Walker speculates that this may be because they view the move as strong and forceful. Either way, remember the mantra "Rock is for rookies," and simply throw Paper at the outset of a game to earn an easy first victory.

"Rock is for rookies" should be kept in mind against more experienced players, too. They won't lead with Rock — it's too obvious — so use Scissors against them. This throw will either beat Paper or tie with itself.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Double trouble

If your opponent makes the same move twice in a row, they almost certainly won't make that move a third time. "People hate being predictable and the perceived hallmark of predictability is to come out with the same throw three times in row," Walker wrote. [Why Aren't We Smarter?]

With that option eliminated, you're guaranteed either a victory or a stalemate in the next round. If you see a "two-Scissor run," for example, your opponent's next move will be either Rock or Paper. If you throw Paper, then, you'll either beat Rock or play to a draw.

Mind tricks

Like a Jedi, you can use the power of suggestion to influence your opponent's next move. When discussing a game, for example, gesture over and over again with the move that you want your opponent to play next. "Believe it or not, when people are not paying attention their subconscious mind will often accept your 'suggestion,'" Walker wrote.

This trick may work because of humans' tendency to imitate one another's actions. A recent study on decision-making in Rock, Paper, Scissors, published in the July 2011 issue of the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, found that players often imitate their opponents' last moves. Human mimicry seems to be involuntary.

Announcing your next move before a round starts also seems to be an effective mind trick, though it'll only work once. If you say you're going with Paper, for example, your opponent thinks you won't, Walker explained. Subconsciously, they'll shy away from Scissors (which beats Paper), and choose Rock or Paper instead. When you do end up throwing Paper, you'll score a victory or a tie.

Don't call it a come back

According to Walker, your opponent will often try to come back from a loss or tie by throwing the move that would have beaten his last one. If he lost using Rock, for example, he'll likely follow up by throwing Paper. Knowing this, you can decide what move to follow with yourself.

Interestingly, monkeys show the same behavioral pattern. In a study detailed in the May 2011 issue of the journal Neuron, researchers at Yale found that rhesus monkeys trained to play Rock, Paper, Scissors tended to react to a loss by playing the move that would have won in the previous round. This suggests monkeys, like humans, are capable of analyzing past results and imagining a different outcome, the researchers said. [The 6 Craziest Animal Experiments]

Humans can take the logic one step further, by imagining what their opponents might be imagining.

Low blow

There's one more ploy to fall back on — that is, if you're willing to sacrifice your honor and integrity for a victory. "When you suggest a game with someone, make no mention of the number of rounds you are going to play. Play the first match and if you win, take it is as a win. If you lose, without missing a beat start playing the 'next' round on the assumption that it was a best two out of three. No doubt you will hear protests from your opponent but stay firm and remind them that 'no one plays best of one,'" Walker wrote. A low blow, but a smart one.

Had no idea so much strategy was possible in Rock, Paper, Scissors? The rules of the game itself may be simple, but the human mind is not.

This article was provided by Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to SPACE.com. Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries, then join us on Facebook. Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.

Most Popular