Family Warns Swimmers About Brain-Eating Amoeba

Jeremy and Julie Lewis were dreading the warm months, when so many people go swimming, and the headlines that emerged in August confirmed their fears. Three more people had died from the brain-eating amoebas that killed their son a year ago.

On Aug. 29, 2010, the Texas couple lost their 7-year-old boy, Kyle, who had been camping with them, his sister and two cousins. He contracted the amoeba while swimming in warm water.

"We don't know why it picked him and it didn't get anybody else," Jeremy Lewis said. "As bad as this is to say, this is luck of the draw."

Since then, he and Julie have founded the Kyle Lewis Amoeba Awareness Foundation and have worked to give others the knowledge they didn't have.

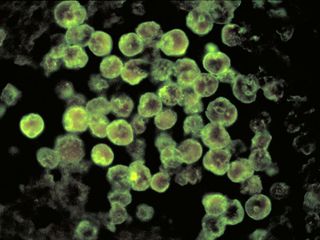

The hot weather of summer brings the urge to cool off with a freshwater dip and, as a result, a peak in infections by the amoeba, Naegleria fowleri, which can kill an unfortunate swimmer within days.

The infection strikes perhaps three people in the United States each year. In many cases it is very easy to prevent — people can avoid warm fresh water or simply pinch their nose, which is where the amoeba enters — but for those who contract it, it is almost always fatal. No treatment exists. [7 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

Three people have already died of it this summer, with a month to go. High temperature is the main indicator that the single-celled blobs will be in the water, and while officials don't have enough information to tie those three cases to any heat wave, July's was a doozy.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This season, it appears two of the three contracted it from taking a dip.

The heat of summer

A 9-year-old Virginia boy apparently contracted the amoeba at a fishing camp, where his mother said he was dunked; a 16-year-old Florida girl became ill after swimming; and it was announced that a young man in Louisiana had died in June after using infected tap water to irrigate his sinuses, the Associated Press reported.

"For the last year, this is what we have been absolutely terrified of — this month, last month and September," Jeremy Lewis said.

The heat of summer typically brings infections because Naegleria fowleri becomes active in warm fresh water — although it can also be found in geothermal pools, inadequately chlorinated swimming pool water or heated tap water of less than 117 degrees Fahrenheit (47 degrees Celsius), according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Although heat this July broke records in the central and eastern regions of the United States, the CDC does not have enough information to connect the heat waves with individual infections, according to Jonathan Yoder, a CDC epidemiologist.

For an infection to occur, the amoeba must travel through the nose and sinuses to the brain. Then it infects the frontal part of the brain, particularly the olfactory bulbs and cerebral cortex. The amoeba does not intend to infect humans, Yoder said; it normally eats bacteria, but once inside the brain, it multiplies and feeds on brain cells. [10 Most Diabolical and Disgusting Parasites]

As of 2008, officials knew of only one well-documented case of a victim surviving.

Kyle's story

The Lewises had planned to visit Gulf Shores, Ala., in late August 2010, but because of the Deepwater Horizon disaster, which had flooded the Gulf of Mexico with crude oil that year, they decided to travel inland with the family camper trailer.

Kyle swam with the other three children in multiple places, and his parents still don't know where he picked up the infection. They returned home on a Saturday, and four days later, in the evening after a baseball game, he developed an intense headache. The Lewises kept him out of school the next day but his condition became progressively worse, with fever, nausea and vomiting. At a hospital, staff recognized his condition as meningitis, an inflammation of the lining of the brain. By Saturday, he was hallucinating, having out-of-body experiences, and appeared to be having trouble recognizing people, Jeremy Lewis said.

At this point, the hospital staff narrowed the cause down to bacterial meningitis or an infection called primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), which is caused by the brain-eating amoeba. Kyle also had spasms: He would start screaming and his body would lock up; then afterward, he would appear unaware of what had just happened, his father said.

Jeremy Lewis awoke at 5:30 a.m. that Sunday to find his son surrounded by doctors and a flat line on the monitor that tracked the boy's brain activity. The boy died later that day.

Until their son became infected, the Lewises had no idea this amoeba even existed. If they had, Kyle might still be alive.

"My wife and I made a decision: People need to know about this," Jeremy Lewis said.

Since 1962, when reporting began, most PAM cases have been people who swam in warm waters during the summer, particularly in southern states. These infections are easily prevented. The CDC recommends avoiding freshwater activities when water temperatures are high, and if you do go in, holding your nose or using nose clips and avoiding disturbing the sediment in shallow, warm fresh water.

The death in Louisiana was unusual because the victim contracted the amoeba from tap water. Health officials later found the amoebas in the home water supply, but not in city water, according to the Associated Press.

The CDC puts the count of documented cases, including the most recent, at 121, averaging out to about three deaths per year in the United States since 1962. (Lewis said the number is slightly higher, at 132, because of 11 additional cases documented retrospectively prior to 1962 in Virginia.)

Lewis feels people dismiss the disease by calling it rare.

"What I want to know as a father who has started a foundation and a father who has lost a child: How many more kids is it going to take before we stop calling it 'rare'?" he said.

Death by drowning is more common, but at least people are aware of the risk when they swim or let their kids swim, he said. "Give us the option, give us the information [so] we can make the decision."

You can follow LiveScience writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Most Popular