Ancient Whales Had Twisted Skulls

Whale skulls might have twisted origins, with the oldest known whales possessing contorted skulls that might have helped them hear better underwater, researchers suggest.

These findings add a new twist to the evolution of the largest animals to have ever lived on Earth.

Modern whales are split into two groups — toothed whales, such as the sperm whale, and baleen whales, such as the humpback whale. Toothed whales are known for biological sonar called echolocation and for asymmetrical skulls, whereas baleen whales, which filter food from water with plates of baleen, lack echolocation and have symmetrical skulls.

Scientists had reasoned that archaeocetes, the ancient whales that gave rise to all modern whales, had symmetrical skulls just as mammals usually do. The assumption was that toothed whales later evolved twisted skulls in concert with echolocation. Such convolutions are known to help other animals hear better — for instance, some owls have one ear opening set higher than the other, an arrangement that helps them break down complex sounds so that they can, for example, discriminate the rustling of leaves around them from the rustling of a mouse on the ground.

However, researchers now find that whale history is a more twisted tale than thought, as archaeocetes had asymmetrical skulls after all.

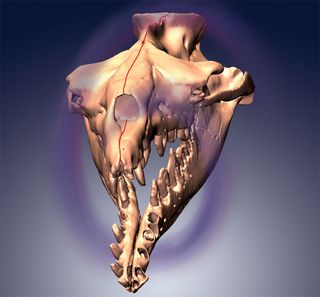

"This shows that asymmetry existed much earlier than previously thought, before the baleen whales and toothed whales split," said researcher Julia Fahlke, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. [See twisted-skull image]

Deformed noggins

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Initially, Fahlke began this research with whale evolution expert Philip Gingerich at the University of Michigan's Museum of Paleontology to learn more about the evolution of the teeth of these leviathans, which would give her information about what early whales ate and how that changed over time.

Fahlke began her work by studying Basilosaurus, a serpent-like, predatory whale that lived 37 million years ago. [Dangers in the Deep: 10 Scariest Sea Creatures]

"We had a 3-D model of the skull that was generated from CT scans, and saw that it was 'deformed,'" Fahlke told LiveScience. "We thought, like everybody else before us, this must have happened during burial and fossilization."

To correct for the deformation, researcher Aaron Wood, now at the University of Florida, straightened out this digital model, but Fahlke found this "corrected" version's jaws did not fit right.

"Finally it dawned on me — maybe archaeocete skulls really were asymmetrical," Fahlke said.

Bends were common

To pursue this idea, Fahlke examined archaeocete skulls at the University of Michigan's Museum of Paleontology, which houses one of the world's largest and most complete fossil collections of the extinct whales. To her surprise, "they all showed the same kind of asymmetry — a leftward bend when you look at them from the top down," she said.

The researchers more rigorously analyzed this asymmetry by investigating six well-preserved skulls from different ancient whale species that showed no signs of artificial deformation; the team measured the way those skulls deviated from a straight line drawn from the snout to the back of skull. They also similarly measured the firmly symmetrical skulls of artiodactyls, the group of terrestrial animals that whales evolved from.

Altogether, the six archaeocete skulls were skewed in shape. "Taken individually, four of them deviate significantly," Fahlke said. The other two appear asymmetrical, but their measurements fall within the range of the symmetrical comparative sample.

Twisted tale

These findings suggest this asymmetry in whale skulls did not evolve with the development of echolocation. Still, the researchers suggest that the twisting may be linked with sound, perhaps helping to improve whale hearing just as it does with owls.

The researchers also found that archaeocetes had other structures similar to ones seen nowadays in toothed whales that might have aided their hearing. These include lumps of fat in their lower jaws that guided sound waves to the ears, as well as an area of bone on the outside of each lower jaw thin enough to vibrate and transmit sound waves into the bodies of fat. Asymmetry in toothed whales then became exaggerated as the whales evolved the ability to echolocate.

This discovery also hints that baleen whales — which count among their number the largest animal to have ever lived, the blue whale— actually had contorted skulls early on in their lineage that later straightened out.

"It would be extremely interesting to study skulls of early baleen whales to see whether they are asymmetrical, and when in baleen whale evolution asymmetry was lost," Fahlke said. "The only obstacle I see is the availability of well-preserved, complete fossil skulls that have not been deformed during burial. These are rare."

Fahlke, Gingerich, Wood and their colleague Robert Welsh detailed their findings online today (Aug. 22) in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.