New Robots Walk Like Humans

WASHINGTON D.C. - In what could be described as one small step for a robot, but a giant leap for robot-kind, a trio of humanoid machines were introduced Thursday, each with the ability to walk in a human-like manner.

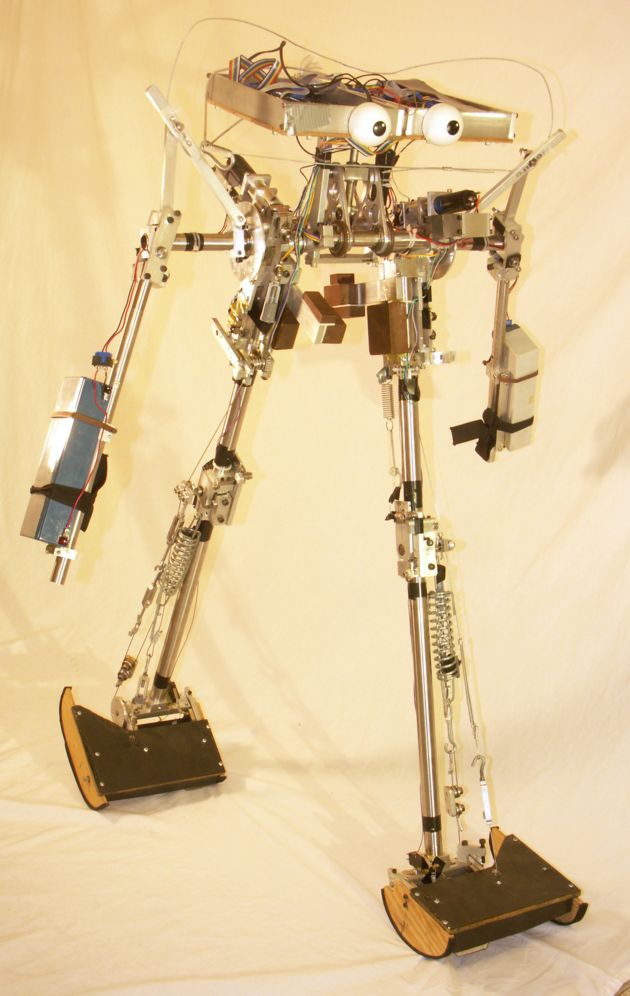

Each bipedal robot has a strikingly human-like gait and appearance. Arms swing for balance. Ankles push off. Eyeballs are added for effect.

One of the robots, from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is named Toddler for its modest stature and the side-to-side wobble of its stride. Denise, a robot created by researchers at Delft University in the Netherlands, stands about as tall as the average woman.

Smart as a toddler

Toddler is the smart one of the bunch. While the others rely on superb mechanical design, Toddler has a brain with less power than that of an ant, but it is able to learn new terrain, "allowing the robot to teach itself to walk in less than 20 minutes, or about 600 steps," scientists said.

The breakthroughs could change the way humanoid robots are built, and they open doors to new types of robotic prostheses -- limbs for people who have lost them. The robots are also expected to shed light on the biomechanics of human walking.

"These innovations are a platform upon which others will build," said Michael Foster, an engineer at the National Science Foundation (NSF) who oversaw the three projects. "This is the foundation for what we may see in robotic control in the future."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The robots were presented today at a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). They are also discussed in the Feb. 18 issue of the journal Science.

More than a toy

Engineers drew from "passive-dynamic" toys dating back to the 1800s that could walk downhill with the help of gravity. Little progress has been made since on getting robots to walk like people.

The new machines navigate level terrain using as little energy as one-half the wattage of a standard compact fluorescent light bulb. The Cornell robot consumes an amount of energy while walking that is comparable to a strolling human of equal weight.

Toy walkers sway from side to side to get their feet off the ground. Humans minimize the swaying and bend their knees to in order to pick up their feet. The Cornell and Delft robots employ this approach.

"Other robots, no matter how smooth they are in control, work to stand first, then base motions on top of that," said Cornell researcher Andy Ruina. "The robots we have here are based on falling, catching yourself and falling again."

Cornell's robot equals human efficiency because it uses energy only to push off, and then gravity brings the foot down, while other robots needlessly use energy to perform all aspects of their effort.

"The Cornell team's passive mechanism helps greatly reduce the power requirement," said Junku Yuh, an NSF expert on intelligent systems. "Their work is very innovative."

Not perfect yet

All three robots swing their arms in synch with the opposite leg for balance. In most ways, though, they are not as versatile as other automatons. Honda's Asimo, for example, can walk backward and up stairs. But Asimo requires at least 10 times more power to achieve such feats.

"The real solution lies somewhere in-between the two," said Steven Collins, a University of Michigan researcher who worked on the Cornell robot. "A robot could use passive dynamics for level or downhill motion, then large motors for high-energy needs like climbing stairs, running or jumping."

Collins is applying what's been learned in an effort to develop better prosthetic feet for humans.

"I think that you can't know how the foot should work until you can understand its role in walking," he said.

The squat Toddler robot gains foot clearance only by leaning sideways, a decidedly non-human approach. But Toddler is remarkable for its ability to learn new terrain and adapt its approach, as would a person.

"On a good day, it will walk on just about any surface and adjust its gait," said MIT postdoctoral researcher Russ Tedrake. "We think it's a principle that's going to scale [up] to a lot of new walking robots."

Big Strides

Meet the robot from ...

Images courtesy each university

Robert is an independent health and science journalist and writer based in Phoenix, Arizona. He is a former editor-in-chief of Live Science with over 20 years of experience as a reporter and editor. He has worked on websites such as Space.com and Tom's Guide, and is a contributor on Medium, covering how we age and how to optimize the mind and body through time. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California.