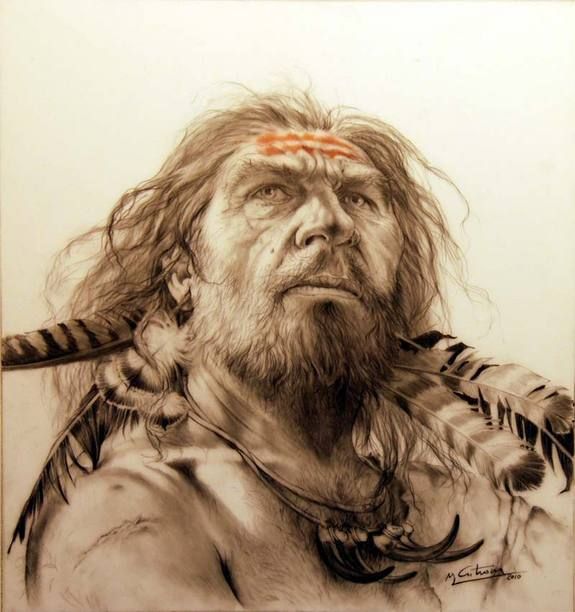

Neanderthal-Human Sex Rarely Produced Kids, Study Suggests

We may have interbred with Neanderthals in the past, but only rarely was that sex successful in producing offspring, scientists now suggest.

Any such dalliances might either have been scarce or only rarely produced offspring, or both, researchers explained.

Recent analyses of Neanderthal genes revealed that many of us have this extinct lineage within our ancestry. Estimates suggest that Neanderthal DNA makes up 1 to 4 percent of modern Eurasian genomes.

To learn more, scientists designed a computer model that estimated how much Neanderthal ancestry would be present in modern humans based on different levels of interbreeding, simulating potential interactions after our ancestors expanded into Neanderthal territory from Africa starting about 50,000 years ago. They next applied this model on the level of Neanderthal DNA seen in modern French and Chinese groups.

Based on this data and model, the researchers discovered the interbreeding success rate was probably less than 2 percent in most scenarios. Assuming that both lineages interacted for about 10,000 years, this means successful interbreeding would have, on average, happened just once every 23 to 50 years, they calculated. [Top 10 Mysteries of the First Humans]

"If more exchange had occurred, we would have become Neanderthals," researcher Laurent Excoffier, a population geneticist at the University Of Berne in Switzerland, told LiveScience.

One possibility is that interbreeding with Neanderthals was more common than such findings suggest, but that any resulting hybrid populations died off before they could leave a significant imprint on the modern human genome in general. However, even if this were true, the amount of Neanderthal DNA making its way into modern human genomes would appear more patchy and variable than it currently does, Excoffier said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This new model also suggests that Europeans and Asians should have different components of Neanderthal ancestry, due to different ways these genes would have mixed after these populations split. They calculate that Asians and Europeans share about one-third of their Neanderthal DNA, but the rest should be unique to each continent.

"By being able to identify which Neanderthal fragments are found in different populations and trying to relate these fragments to different Neanderthal populations established in different parts of Eurasia, we would perhaps be able to infer where those admixture events occurred and thus precisely retrace past routes of migrations of our ancestors," Excoffier said.

Future research could also investigate the newfound lineage of the Denisovans, which lived in what is now Siberia. Genetic analysis of their fossils suggests their DNA makes up 4 to 6 percent of modern Melanesian genomes. Recent research has also suggested that modern humans had sex regularly with a mysterious, now-extinct relative in Africa.

Excoffier and colleague Mathias Currat detailed their findings online today (Sept. 12) in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.