Oldest Viruses Infected Insects 300 Million Years Ago

Viruses were already infecting organisms some 300 million years ago, suggests a new study on what may be the oldest date yet for the emergence of an insect-infecting virus.

"This is the oldest date ever proposed for a virus," said study researcher Elisabeth Herniou, of the University of Tours in France.

"Knowing about ancient viruses can help us distinguish evolutionary processes resulting from historical interaction as opposed to adaptive processes happening in the present day," Herniou added in an email to LiveScience.

Waspy viruses

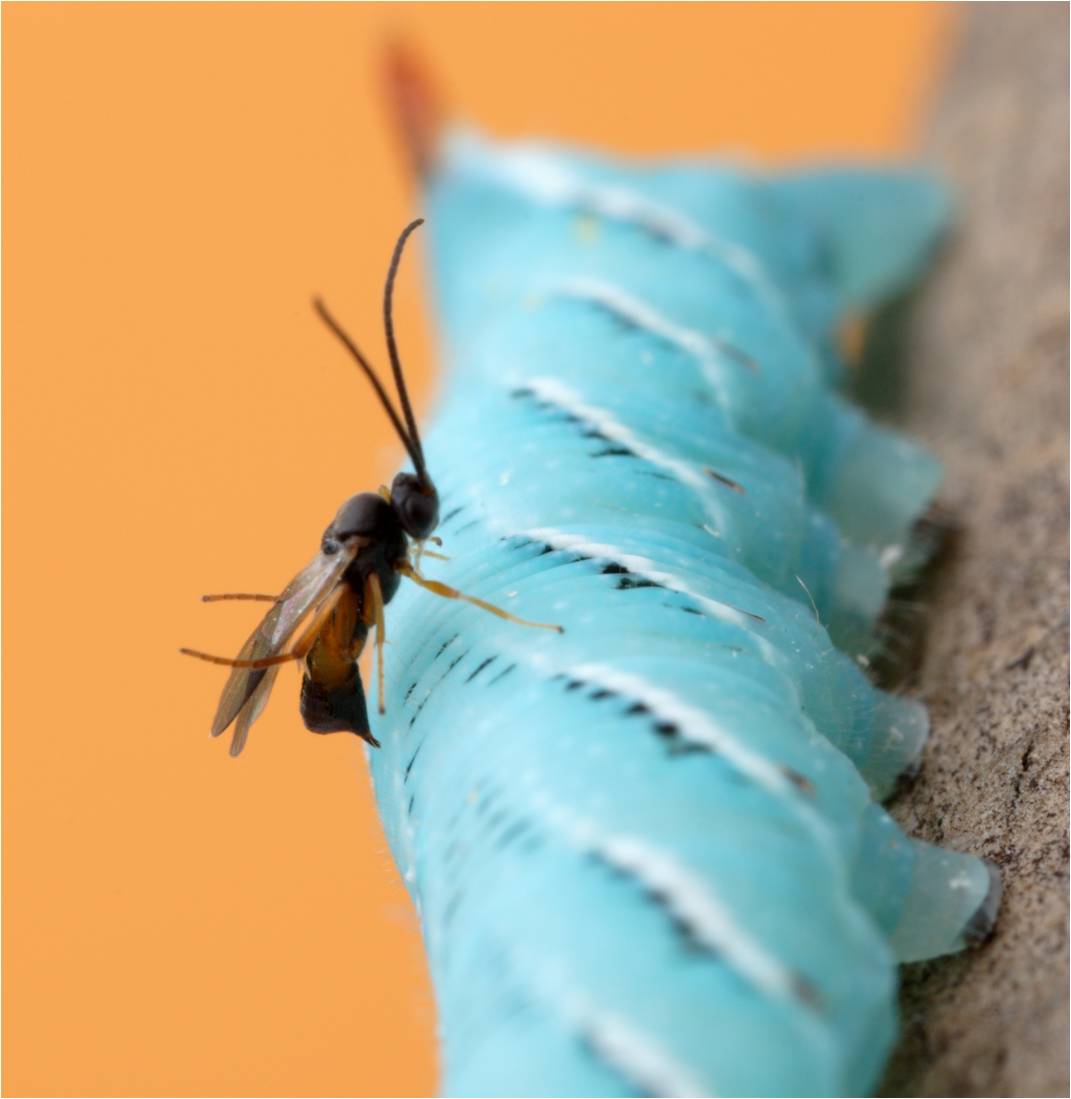

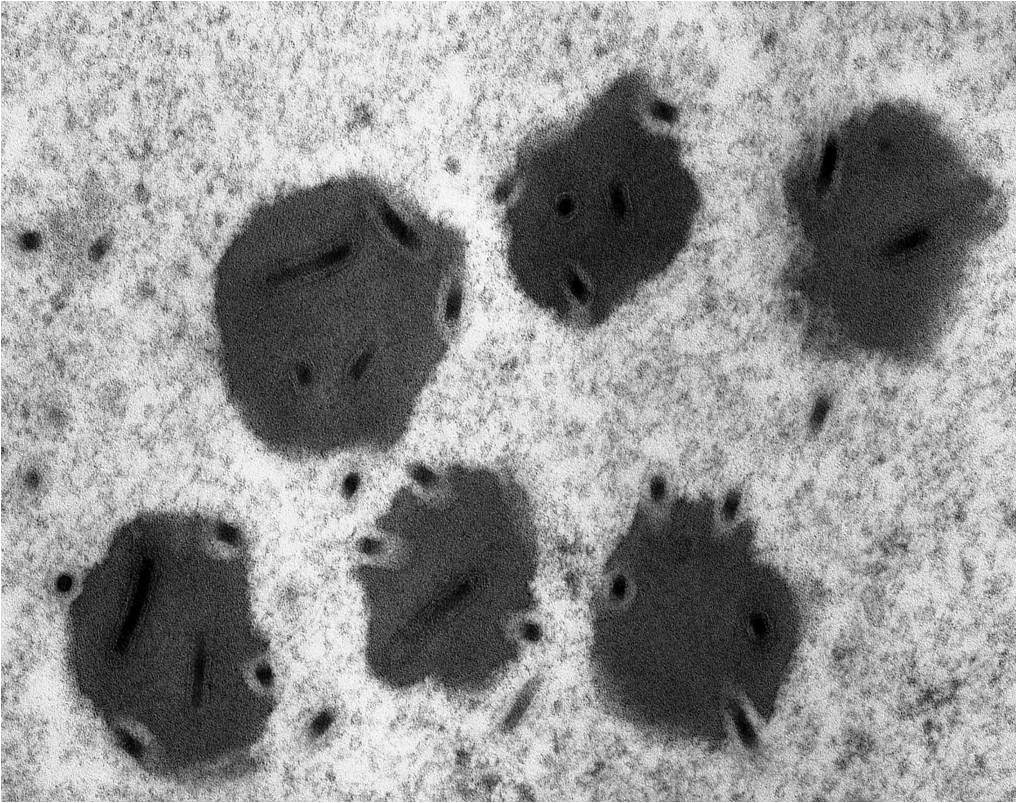

Viruses, which are packets of DNA in a protein shell, can't reproduce on their own and so must take over DNA and protein making machinery of a host in order to survive. To find out how old insect viruses are, researchers studied a virus that parasitic wasps use for their own good.

The wasps use their onboard viruses, called bracoviruses, to control the development and immunity of the caterpillars they parasitize. The wasps use the viral genes to make virus-like particles containing genes for a toxin, which they insert into their caterpillar prey when they lay their eggs.

The infected caterpillar then acts as an incubator for the wasp eggs. Meanwhile, the toxin is made by the caterpillar and poisons its immune system, causes paralysis and stops the caterpillar from pupating.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Viral family tree

To find out when viruses first infected insects, the researchers compared the genes of this wasp bracovirus with genes of related free-living insect viruses (those that haven't inserted their genes into a host genome) called nudiviruses. They found 19 genes in both the wasp bracovirus and the nudivirus, about 10-15 percent of the nudivirus genome.

Next, they looked at the different strains of bracoviruses in different wasps, finding that the bracoviruses and their free-living cousins have been evolving separately for at least 100 million years.

By figuring out how different the ancestral bracovirus was from its parental nudivirus when it entered the wasp, the researchers can calculate backwards and determine when the two viruses had a common ancestor. According to the researchers' data, nudiviruses started appearing around 222 million years ago, then spun off the bracoviruses about 190 million years ago.

By comparing the nudiviruses to their cousins the baculoviruses, another free-living insect virus, the researchers determined that the two groups split about 310 million years ago.

Ancestral viruses

These ancient viruses would have been similar to modern viruses, with similar genes. "The genes that were used in our study would have been there already in this 300-million-year ancestor," Herniou said.

This date, 300 million years ago, is as ancient as insects themselves. "Our insect viruses are already present right from the beginning from the evolution of insects," Herniou said. Viruses were still around during the age of dinosaurs, and survived the mass extinction that killed them. They survive to this day and have been found to infect every type of life; there are even viruses that infect viruses.

"Because insects were already infected by some viruses, you can probably extend that to other kinds of multicellular hosts," Herniou said. Viruses could have been infecting other forms of life on the Earth at that time, and in later eras.

The study was published today (Sept. 12) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.