Ancient Toothy Fish Once Prowled Arctic Waters

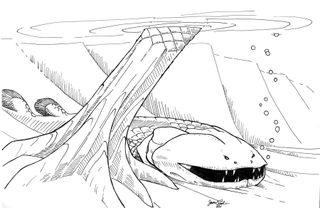

A large predatory fish with a fearsome mouth once prowled ancient North American waterways, suggests an analysis of fossilized remains of the beast.

The lobe-finned fish, now called Laccognathus embryi, probably grew to about 5 or 6 feet long (1.5 to 1.8 meters) and had a wide head with small eyes and robust jaws lined with large piercing teeth. The beast was likely a bottom-dweller, waiting on the seafloor to lunge at prey passing by. [Album of Scary Sea Creatures]

"I wouldn't want to be wading or swimming in waters where this animal lurked," said study researcher Edward Daeschler, a curator of vertebrate zoology at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia.

The lobe-finned fish likely preyed on armored placoderms and lungfish, lead author Jason Downs, also of the Academy of Natural Sciences, told LiveScience. "Laccognathus embryi, with its powerful jaws and long, sharp teeth is certainly a predatory animal that is likely to have eaten the other aquatic vertebrates that lived in the same streams and rivers."

The team discovered the 375-million-year-old fish fossil on Ellesmere Island in the remote Nunavut Territory of Arctic Canada, though back then conditions would have been subtropical, the researchers said.

In the past, the researchers also discovered Tiktaalik roseae, a transitional animal considered a "missing link" between fish and the earliest limbed animals, side-by-side with L. embryi at the same site. That suggests the two lived side-by-side as well, the researchers speculate.

"Both are predators, and there is certainly a possibility that they competed for prey," Downs said. "It is also possible that they lived at different depths or even employed different feeding strategies that would have enabled them to establish unique feeding niches in these environments."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Though the team discovered the first L. embryi fossil some 10 years ago, they only recently described the species in the current issue of the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, after several seasons of collecting additional samples from the field and analyzing them.

"This study is the culmination of a lot of work in the field, in the fossil lab, and in the office," Downs said.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescienceand on Facebook.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Most Popular