Scientists have engineered viruses to attack and destroy mega-colonies of potentially harmful bacteria called biofilms.

The work is one of the latest potential applications to emerge from synthetic biology, a burgeoning field that aims to change the genomes of organisms on large scales to make them more useful to humans or to even craft new life forms from scratch.

“Our results show we can do simple things with synthetic biology that have potentially useful results,” said study team member Timothy Lu, a doctoral student in the Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology.

The engineered bacteria-attacking virus, or “phage,” was built using a “plug and play” library of genes. The same approach could be used to build viruses custom tailored to target specific bacteria species, the researchers say.

“The library could contain different phages that target different species or strains of bacteria, each constructed using related design principles to express different enzymes,” said study leader James Collins, a biomedical engineer at Boston University.

Bacterial cities

The finding, detailed in the July 3 issue of the journal of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, could lead to industrial “cleaners,” such as phages to clear slime in food processing plants or new types of phage-based antibiotics for humans or livestock.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

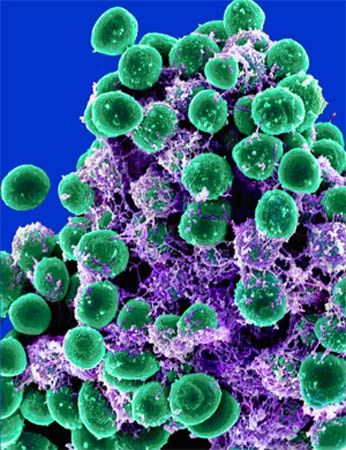

Biofilms form when large aggregates of bacteria, often of several species, bind together using adhesive molecules to form a slimy layer. Biofilms can form almost anywhere, even on your teeth if you don’t brush for a day or two. They are often resistant to many types of antibiotics, and when they accumulate in hard-to-reach places, such as the insides of food processing machines or medical catheters, they can become persistent sources of infection.

Lu and Collins inserted a gene that produces an enzyme called dispersin B (DspB) into the genome of T7, a virus that attacks the bacteria Escherichia coli. DspB, recently discovered in sewer phages, is capable of degrading a biofilm’s molecular scaffolding, or “extracellular matrix.”

The researchers tested their engineered T7 phage on E. coli biofilms and found that it eliminated 99.997 percent of the microbes, which is far better than the phage’s non-engineered cousin.

From the ground up

While the new research involves tweaking the genomes of known organisms, other synthetic biologists aim to create a synthetic microbe with the minimum gene set necessary for life.

Researchers led by biologist J. Craig Venter announced recently they had overcome a significant hurdle toward this goal. The team showed that a cell could be brought to life, or “booted up,” using only naked DNA from another species.

Their next step is to craft a synthetic genome and insert it into a surrogate cell, which could then reproduce. Venter has hinted that his team is mere months away from announcing the first synthetic life form.

- Making Life from Scratch

- Breakthrough Could Lead to Artificial Life Forms

- The Invisible World: All About Microbes

Why America is losing its 50-year 'war on cancer,' according to scientist Nafis Hasan

What is double pneumonia? Pope Francis's diagnosis explained.