Can You Inherit a Long Life?

Updated at 6:30 p.m. ET, Oct. 19

Parents may be passing more to their offspring than their DNA. A new study shows some worms pass along non-genetic changes that extend the lives of their babies up to 30 percent.

Rather than changes to the actual genetic code, epigenetic changes are molecular markers that control how and when genes are expressed, or "turned on." These controls seem to be how the environment impacts a persons' genetic nature. For instance, a recent study on diet showed that what a mouse's parents ate affected the offspring's likelihood of getting cancer. Studies in humans have suggested that if your paternal grandfather went hungry, you are at a greater risk for heart disease and obesity.

The new study's results "could potentially suggest that whatever one does during their own life span in terms of environment could have an impact on the lives of their descendents," study researcher Anne Brunet, of Stanford University, told LiveScience. "This could impact how long the organism lives, even though it doesn't affect the genes themselves."

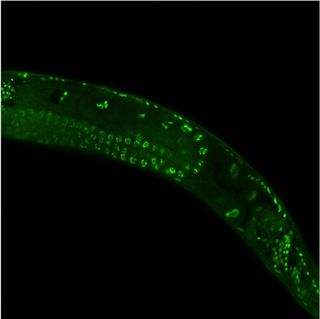

The study was conducted in the model organism C. elegans, a small, wormlike nematode often used in experiments as a stand-in for humans because of their genetic similarities. Even so, the researchers aren't sure how their results would apply to human life span. They are currently studying fish and mice to see if their findings hold true in different species.

Genes or epigenes?

Our DNA holds the code for life, but this code can be adapted based on how DNA is twisted together with proteins. Changes to these proteins are called "epigenetic," a word that literally means "on top of the genome." [Epigenetics: A Revolutionary Look at How Humans Work]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Modifications to proteins called histones that hold DNA together can turn genes off by adding a molecule called a methyl group (a carbon-hydrogen molecule), and can turn genes on by removing the methyl. These modifications can be caused by a variety of things in the environment, including diet or exposure to toxins.

The new study shows that, contrary to popular belief, some of these changes survive fertilization. Which ones survive, and how, are questions researchers are still trying to answer.

"What this finding suggests is that it's [the epigenome] not completely reset and there is epigenetic inheritance that isn't encoded by the genome that is sill transmissible between generations," Brunet said.

Inherited longevity

The researchers found that when they mutated the protein complex that adds a methyl group to a specific histone protein, the nematodes lived up to 30 percent longer than the non-mutants. When the mutant nematodes reproduced with normal nematodes, their offspring (even those without the mutation) lived up to 30 percent longer. The methyl addition that caused the extended lifespan seemed to be passed down, even if the actual mutation wasn't.

For a nematode, which lives 15 to 20 days in the lab, an extra five or six days is a big boost. This would be like a human, instead of living to 80, living past 100.

The complex seems to turn off pro-aging genes, though what those genes are and how they work, the researchers aren't sure. "We really don't know yet what the mechanisms are, even in the parents, in which this complex manipulates life span," Brunet told LiveScience. "We do see genes that are involved in aging that are regulated by this complex."

Human implications

While the researchers aren't sure about the protein's effect on human longevity yet, the finding is also important in studies of adult stem cells. Adult stem cells are normal cells that are 'reprogrammed' and supposedly wiped free of their epigenetic modifications. If this wiping process isn't thorough, leftover modifications could compromise therapies using these cells.

"The finding is fascinating," David Sweatt, a researcher at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, told LiveScience in an email. "The observations are also consistent with the emerging concept of 'soft inheritance,' whereby epigenetic mechanism may drive a molecular memory of ancestral experience over several generations."

Silvia Gravina, a researcher from the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, suggested that epigenetic inheritance like that in the study could augment traditional "longevity" genes in human centenarians and their offspring.

"This finding supports the captivating and novel concept that health and general physiology can be affected not only by the interplay of our own genes and conditions of life, but also by the inherited effects of the interplay of our own genes and the environment of our ancestors," Gravina said, also by email.

Neither Sweatt nor Gravina was involved in the study, which was published Oct. 19 in the journal Nature.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Editor’s Note: Silvia Gravina’s statements were updated to clarify that epigenetics could add to, not replace, traditional genetic causes of longevity in humans.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.