The Science of Death: 10 Tales from the Crypt & Beyond

Science of Death

Science has a macabre side. Archaeologists and forensic scientists routinely uncover evidence of all sorts of past horrors: Bones gnawed by prehistoric cannibals, the graves of murdered infants, as well as the gruesome transformations that time and decomposition bring, such as bones wrapped in death wax. And don't forget zombie insects, nature's own undead; the neurology of decapitation and near-death experiences. Here's a selection of some of our most delightfully morbid stories, listed in no particular order.

Vampire Plague

There's nothing like archaeology to dig up ancient tales of death, disease and torment. This particular discovery, of the skull of a woman with a rock shoved in her mouth was found among 16th-century plague victims in a mass grave on the Venetian island of Lazzaretto Nuovo.

In 1576, the Venetian plague killed up to 50,000 people. Without the benefit of science, people found other explanations, including vampires. Gravediggers believed this woman was among them, and put the rock in her mouth.

In the absence of medical science, vampires were just one of many possible contemporary explanations for the spread of the Venetian plague in 1576, which ran rampant through the city and ultimately killed up to 50,000 people, some officials estimate. [Read full story]

Perfect Site for a Haunting

In 1912, excavators in the English countryside unearthed the remains of dozens of babies — the exact number isn't clear — who died at birth and were buried on the grounds of a Roman-era villa about 1,800 years ago. The remains then disappeared for almost a century before an archaeologist discovered them packed into boxes that once held loose cigarettes and gun cartridge boxes in a museum archive. An examination of 35 of the remains revealed that most were 38 to 40 weeks old at the time of death — a pattern than suggests infanticide. [Read full story]

The Ravages of Time

After death, a new story begins: decomposition. And the breakdown of our bodies can take some odd turns, as archaeologists and forensic scientists know. Under certain conditions, fat in the body's soft tissue morphs into a hardy soap-like substance, called adipocere, which acts as a preservative.

In 1997, a headless corpse, wrapped in adipocere and dusted with a blue mineral, turned up floating in a bay of Lake Brienz in Switzerland. At first, investigator Michael Thali, now at the University of Zurich, guessed it to be a few months or possibly years old. After sawing away the adipocere to investigate, he and his colleagues found preserved organs, including a digestive track containing cherry pits; and after examining the remains, they concluded the body was a man who lived as much as 300 years ago. [Read full story]

Zombie Ants

No exploration of death would be complete without the undead; in this case, nature's own zombies: Ants infected by a fungus that directs them to march to their doom, so it can spread its spores. Scientists have identified multiple species of the zombie fungus, which uses mysterious chemicals to control the ant. After infecting an ant, the fungus makes it leave its colony and bite down on a leaf with a death grip that will keep the ant in place after the fungus kills it and grows a stalk out of its head to send out spores. By watching 16 infected ants in Thai rain forest, the researchers saw them take their final bites around noon. [See images of zombie ants]

Zombie Caterpillars

This time the zombifier is a single gene in a virus. A species of baculovirus that infects only gypsy moths takes control of the caterpillars, stops them from molting and sends them climbing up trees. Once high in the tree leaves, the caterpillars die, and turn to goo, which drips the virus particles back down onto the leaves below where new caterpillars can pick them up. An experiment showed that caterpillars infected with a virus missing the special gene didn't climb up before dying. [Read full story]

Mathematically Dead

One skeptic, University of Central Florida physics professor Costas Efthimiou, set out to disprove the existence of vampires.

Here's his calculation: There were 536,870,911 human beings on Jan 1, 1600. Assuming the first vampire came into existence that day and bit one person a month, changing him or her into a vampire, there would have been two vampires by Feb. 1 of that year, then, on March 1, four vampires, and so on. If vampirism spread like this, it would only take two-and-a-half years to convert the entire human population into vampires with nobody left to feed on. [Read full story]

Your Odds of Dying

In spite of the attention natural disasters receive, like the devastating tsunami that hit Japan in March 2011, you're more likely to kill yourself or fall to your death than die in natural disaster. So if you need something to keep you up at night, the odds say U.S. residents should worry about heart disease or cancer, not tsunamis, asteroid impacts or fireworks discharges. [End of the World? Top Doomsday Fears]

Near-Death Experiences

Approximately 3 percent of the U.S. population reports having had a near-death experience, according to a Gallup poll. Now, science is beginning to explain how our brains create these experiences. For instance, research has found that out-of-body experiences can be created by stimulating the right temporoparietal junction in the brain. This suggests out-of-body experiences are related to a failure to integrate sensory information from the body in this part of the brain. [Top 10 Mysteries of the Mind]

Life after Decapitation

The electrical activity in rats' brains goes dead about 17 seconds after they are decapitated, research has shown. But about a minute afterward, a slow, large electrical wave surges through the rats' brains. Some researcher have interpreted this as a sign of irreversible brain death. However, others have argued that, even after this final wave, brain cells could, in theory, still be re-animated. [Read full story]

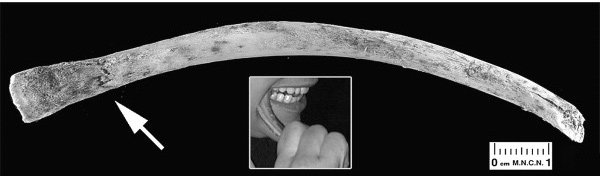

Something (or Someone) to Chew on

Researchers asked Europeans and Africans to gnaw on pork and mutton bones, studied the marks their teeth made, and then compared them with similar marks on human bones found at prehistoric sites in England and Spain. The findings suggested that prehistoric people may have responded to a lack of nutrition with cannibalism. [Read full story]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.