Ancient Whale Taken Down by Shark, Tooth Marks Reveal

The sharp eyes of an Italian stonecutter were the first to spy a new ancient species of whale 40 million years after it was first encased in stone.

The fossil, of a new ancient whale species called Aegyptocetus tarfa, was found in a block of limestone headed to decorate an Italian building. The stonecutter realized after slicing through the stone block that he was looking at the cross section of a fossilized skull, and he contacted Giovanni Bianucci, a researcher at the University of Pisa, to help identify it.

The whale belongs to a group of whales ancestral to all of today's modern whales, including the toothed whales, like the dolphin, and baleen whales, like the blue whale.

The remains also show the scars of a shark attack, which may have led to the beast's demise.

Stony skull

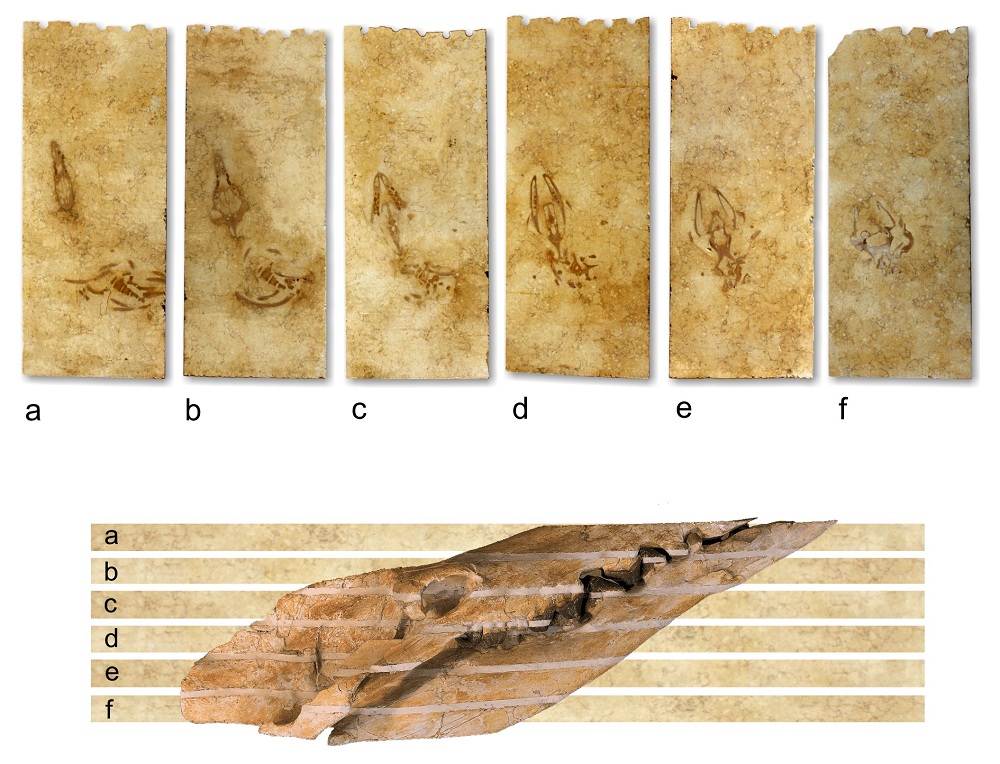

After the stonecutter's discovery in 2003, the six marble slabs containing the whale remains were put on display in the Natural History Museum of Pisa University, in Italy. Later, Bianucci decided to reconstruct the skeleton from the slabs. Because they knew the thickness of the cuts, they were able to figure out what the skeleton actually looked like before it was cut apart. [See images of the whale being removed from limestone]

The limestone block containing the whale skull and upper torso came from a quarry in Egypt. Since the fossilized bones and the limestone are about the same hardness, they wear away at the same rate. That makes the find a rare one, as typicallyfossils are discovered as the stone around them erodes, allowing the fossilized bone to stick out of the rock. In limestone, the fossilized bone is worn at the same time as the rock.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The find is an "interesting fossil and an even more interesting story of discovery," said J.G.M. "Hans" Thewissen, a researcher not involved in the study from Northeast Ohio Medical University. "As a fossil, it adds understanding to the diversity of Eocene [the period from about 55 million to 35 million years ago] whales, this is a new species, and it is a very nice fossil."

Shifting senses

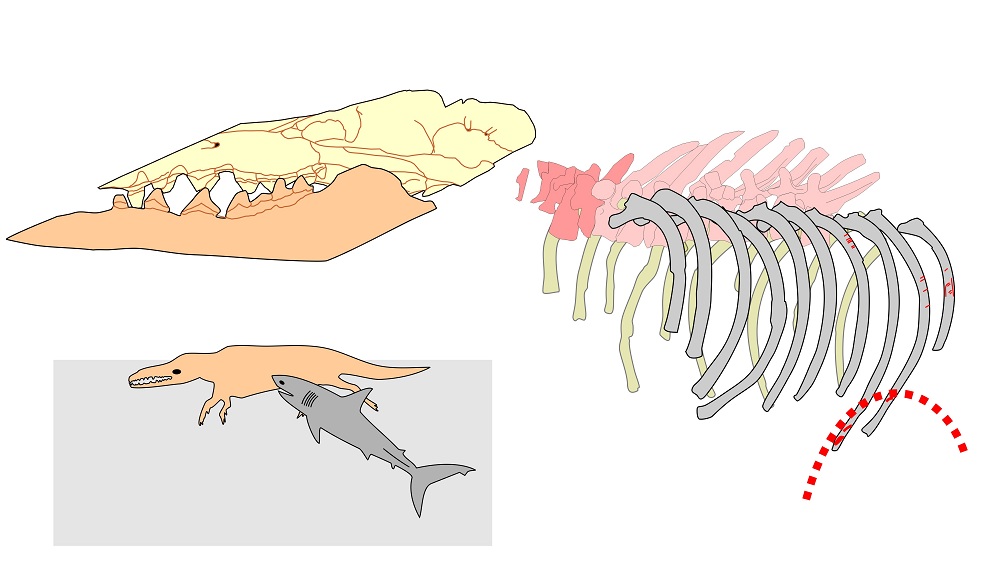

Bianucci told Philip Gingerich, a researcher at the University of Michigan, about the find. Gingerich, an expert on ancient whales, told LiveScience that the whale would have been about 9 feet to 10 feet long (about 3 meters) and weighed about 650 pounds (295 kilograms).

From the fossilized skull, the researchers were able to take a close look at how the whale interacted with its surroundings. The eardrums were hardened, a characteristic of modern whales that allows them to hear the ocean around them. The whales didn't, however, have the ability to make the sounds that current whales do, as the ancient whale skull showed no evidence of modern sound-making structures. The whale's nose structures did suggest that when alive, it had a sense of smell, a sense that it mostly lost in modern whales.

"This is the first time we've seen a really nice cross-section that shows that the animal still had the ability to smell," Gingerich said. "An interesting thing was to see how well-developed the sense of smell was in whales, since it's hardly there anymore in modern whales."

Ancient attack

The whale most likely met its demise at the mouth of an ancient shark. Tooth marks on its ribcage indicate it might have been attacked from its right flank, similar to how modern sharks attack their prey. The researchers were even able to see the striations the teeth left in the rib bones.

"We think that the shark attacked from the flank from behind, which is known to be how sharks attack larger things today," Gingerich said. "We don’t know if that's how the whale died, but it's pretty likely."

After the vicious attack, the carcass of the whale lay on the bottom of the ocean for quite some time (probably months to years) before it was fossilized; the carcass attracted barnacles, which left pits on only one side of its body. The legs and lower half of the whale are missing, which means they could have been torn off during the original attack, or scavenged and moved from the body at a later date.

The paper was published Monday (Nov. 7) in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.