Skin and Bones: Inside Baby Mammoths

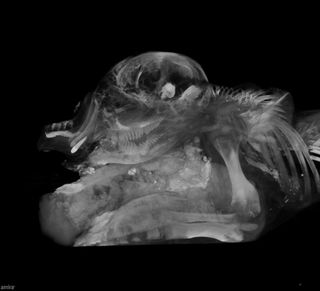

Lyuba

Lyuba, a baby mammoth that suffocated in thick mud 42,000 years ago, gets the high-tech treatment with this computed tomography (CT) scan.

Khroma

An older mammoth, Khroma, also came from the Siberian permafrost, where she died as a baby.

Khroma

A view of Khroma's skull, showing her teeth. The mammoth had unusual thick bony structures on her skull, which researchers compared to mustache-like structures.

Khroma, Oblique

An oblique view of Khroma's entire body. The mammoth was originally identified as male, but turned out to be female.

Khroma in Profile

A somewhat crumpled, but almost entirely complete specimen, Khroma has been on display around the world.

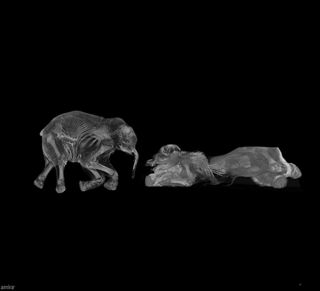

Family Portrait

Two baby mammoths, Lyuba and Khroma, side-by-side.

Mammoth Bones

This image reveals a sharp look at baby mammoth Lyuba's ribs. Khroma's spine is well-defined.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

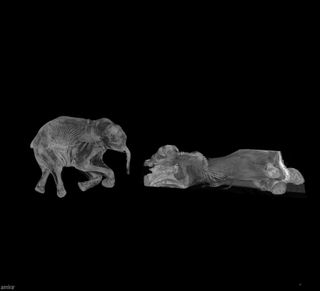

Mammoth Profiles

Lyuba and Khroma in profile. Despite being presumably the same species, the mammoths had very different skeletal structures. The reason for this is still an Ice Age mystery.

Two Mammoth Mysteries

The scans revealed not only bones, but muscle, organs and even stomach contents. Researchers hope to learn more about these animal's lives and adaptations to their frigid Siberian homes.

Lyuba

Lyuba was almost perfectly preserved because lactic-acid producing bacteria colonized her body shortly after death, in essence "pickling" her and preserving her from hungry scavengers.

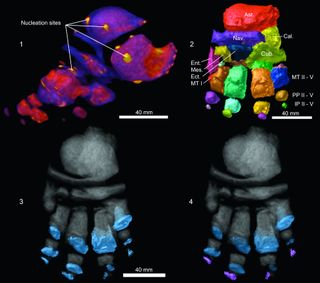

Khroma's feet

Here, a CT scan reveals a look at Khroma's feet, with the joint capsules colorized.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.