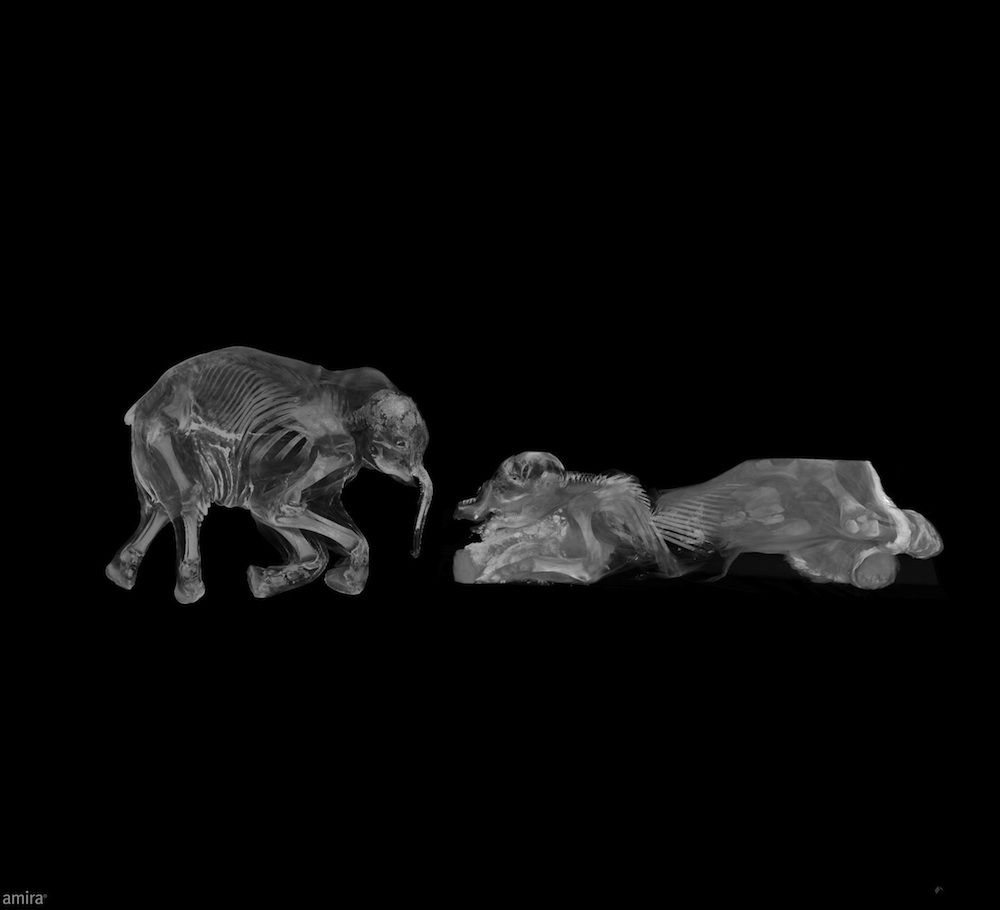

Baby Mammoth Innards Revealed in X-Ray Images

High-tech scans of two baby mammoths pulled from the Siberian permafrost reveal that one, originally identified as male, was in fact a female.

In addition, the scans showed major skeletal differences between the two mammoths, perhaps representing evolutionary change in the mammoth lineage.

"A lot of what we've done with mammoths in the past has been done based on dental anatomy, based on what we can see from teeth," study researcher Ethan Shirley of the University of Michigan Museum of Paleontology told LiveScience here in Las Vegas at the annual meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.

"Now, we have teeth … but we also have the whole rest of the baby mammoth: skin, fat, muscle, bone, everything in between," Shirley added. [See X-ray images of baby mammoths]

Even the contents of the animals' stomachs are preserved, Shirley said, a clue as to the diet of the Ice-Age beasts.

Two little mammoths

The two mammoths, dubbed "Lyuba" and "Khroma" were found in 2007 and 2009, respectively. Lyuba is 42,000 years old, while Khroma was found in geologically older sediments. Lyuba is female and is believed to have suffocated in thick mud after getting stuck. Khroma was originally pegged as male. Khroma was originally thought to have died of an anthrax infection, prompting scientists to irradiate the mummy for fear of infection, but further research suggests the mammoth died of some other cause, said study researcher Daniel Fisher, also of the University of Michigan museum.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new computed tomography (CT) scans, however, allow an inside look at Khroma's reproductive tract, revealing he is a she. It turns out that the surface anatomy of baby mammoth genitals is not very different between males and females, Fisher said.

"It's when you follow it inwards, which we were not able to do visually or tactilely, that the differences become manifest," Fisher told LiveScience, explaining that the tissue believed to be Khroma's penis was in fact a clitoris.

The scans also exposed Lyuba and Khroma's skeletons for the first time. Although both are the same species, there were major differences in their bones, Shirley said. Lyuba's front legs are proportionally longer than Khroma's, and Khroma has bony ridges where her tusks would have erupted that Lyuba lacks, he said.

"That was all really a surprise," Shirley said.

Mammoths adapting

It's too early to say what those anatomical differences mean, Fisher said. It could be that mammoth populations varied slightly over the vast geography of Siberia. Or perhaps evolution refined the mammoth line over the time between Khroma's death and Lyuba's life.

"In any case, it gives us a clearer picture of the sort of variation that exists within lineages of organisms like mammoths," Fisher said. "It is variation like this that natural selection operates on to produce evolutionary change."

The scans are also turning up smaller revelations about mammoth life. For example, Fisher said, Lyuba has much larger kidneys than researchers would have expected. It's possible these massive organs allowed mammoths to process urine more effectively, excluding waste while holding on to water.

"They're living in a cold, cold environment where essentially all available water is frozen, and having to pee a lot would get rid of a lot of body water that would have to be replaced by eating snow or ice, which is cold," Fisher said. "So it's much better just to recycle the urine. Nobody's ever had an idea that that aspect of physiology was part of mammoth adaptation to the cold."

Editor's Note: This article has been corrected to reflect Khroma's cause of death and to remove a reference to a traveling museum exhibit starring Lyuba. The exhibit is scheduled to open at the Missouri History Museum in St. Louis, but may include a replica of the mammoth instead of the mummy itself.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.