'Jealous' Hermaphrodite Shrimp Murder Their Rivals

Like creepy stalkers, cleaner shrimp won't share their partner with anyone else. When placed in groups of more than two, the creatures attack in the dark of night, killing off the competition.

"We enlarged the group size to triplets and quartets, and we observed the molting cycle and the interactions between individuals,'' study researcher Janine Wong, of the University of Basel in Switzerland, told LiveScience."In this species, the shrimp usually live in pairs. We were wondering, because monogamy is quite susceptible to cheating, if these individuals would stay in monogamous pairs."

They didn't.

Sperm or egg?

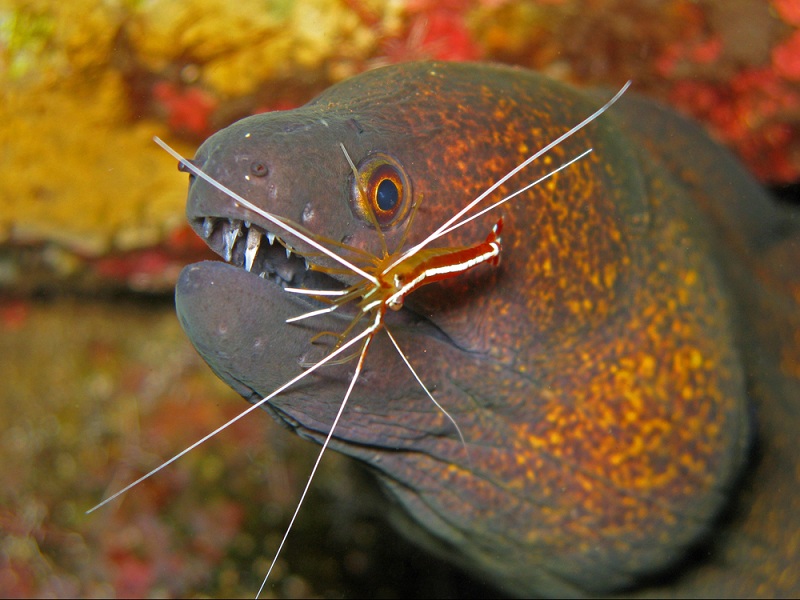

Cleaner shrimp (Lysmata amboinensis) pairs make their living picking parasites from fish. They stake out their cleaning stations and wait for fish to stop by their storefront. Each shrimp is a hermaphrodite, meaning it can reproduce as both a male and a female, though it can't fertilize its own eggs.

In times of high competition for a mate, each shrimp makes fewer eggs and more sperm, since the eggs are more cost-intensive to produce and one individual's sperm can fertilize many eggs. The goal is to pass on one's genes, and in this case, sperm will do the trick. When two shrimp pair up in a monogamous relationship, however, they shift to making more eggs and less sperm, since there isn't competition for who is going to fertilize whom. [Top 10 Monogamous Animals]

This type of social monogamy is only found in shrimp with cleaning behavior, Wong said, possibly because these cleaner shrimp stick to their territory instead of going around and searching for food.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Shrimp squabbles

Wong and her colleague Nico Michiels, at the University of Tuebingen in Germany, placed two, three or four cleaner shrimp together in a group (repeated 10 times for each condition). By the time 42 days had passed, every tank was down to two shrimp.

The shrimp are only vulnerable to attack right after they have molted, when their outer skins made of chitin are thin. To avoid predators, they molt during the night. Though the shrimp weren't aggressive during the day, at night they ganged up on any freshly molted tank-mates.

"During daytime, there were no aggressive interactions observable, they were just sitting next to each other or ignoring each other. You couldn't predict from their behavior during the daytime who would be the next victim," Wong said. "The individual that died had just molted a few hours before. Because the carapace [shell] didn't harden yet, they were very vulnerable and easy targets."

Territorial terrors

These shrimp, regardless of whether they are paired up, usually molt every two weeks. In high-competition environments, with three or four shrimp per tank, they molt less frequently. Wong's team noticed that after murdering their extra tank mates, the killer shrimp would return to their regular molting schedule.

In the threesomes, the victim was usually the smallest in the tank, but in the quartet, the same trend wasn't obvious. It wasn't always the first shrimp to molt that was done in, either. The researchers aren't sure yet why certain shrimp lived while others were killed.

This tank is an artificial environment compared with the wild, where the shrimp could just swim away when threatened. Researchers aren't sure how these L. amboinensis act in the wild, but they are very territorial. It's more likely that a "third wheel" type would be chased away from the mating pair's cleaning station, and the murderous rage would be much lower.

The study was published Thursday (Nov. 10) in the journal Frontiers of Zoology.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.