Crusader's Arabic Inscription No Longer Lost in Translation

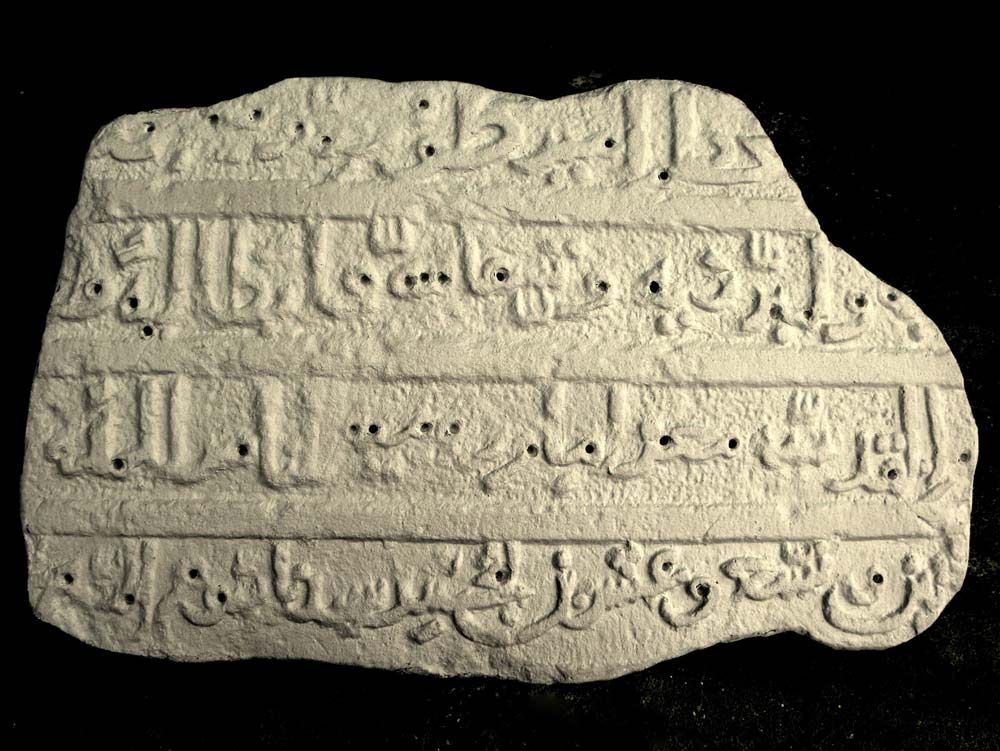

A rare Arabic inscription from the Crusades has been deciphered, with scientists finding the marble slab bears the name of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, a colorful Christian ruler known for his tolerance of the Muslim world.

Part of the inscription reads: "1229 of the Incarnation of our Lord Jesus the Messiah."

The 800-year-old inscription was fixed years ago in the wall of a building in Tel Aviv, though the researchers think it originally sat in Jaffa's city wall. To date, no other Crusader inscription in the Arabic language has been found in the Middle East.

"He was a Christian king who came from Sicily, the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, and he wrote his inscription in Arabic," said Moshe Sharon, of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, adding that it would be like the U.S. president traveling to a region and leaving an inscription in that area's language.

Tricky translation

Until now, others who had examined the inscription had suggested it came from a 19th-century gravestone, not realizing the date in the last line referred to the Christian calendar, according to Sharon.

"It's not so easy to read Arabic inscriptions, and particularly this one, which was written in an unusual script, and it is on stone and it is 800 years old," Sharon said of the difficulty in translating the engraving. [Photos of Early Christian Inscriptions]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Though Frederick II, who was known to have a deep familiarity with Arabic, may not have directly engraved the stone, "it was written by an artist and this artist decided to create a special script for this royal inscription and it took us a very long time until we were able to find out that, in fact, we were reading a Christian inscription," Sharon said during a telephone interview.

Sharon and Hebrew University colleague Ami Shrager are preparing to submit a manuscript describing the work to the scientific journal Crusades.

"The emperor gives his name, and he lists all the countries in which he rules, which is not usual in inscriptions, although we find it in literary sources," Sharon said.

A peaceful crusader

The Crusades were religious wars whose goal was to restore Christianity to holy places in and near Jerusalem, with the First Crusade beginning in 1095 and the Seventh and Eighth Crusades ending in 1291.

Frederick II led the Sixth Crusade, and succeeded without resorting to violence, it seems.

"Basically, the emperor went as a crusader to the Holy Land in 1228 in order to conquer that part of the Holy Land," Sharon told LiveScience, "but instead of fighting they discussed things and in the end of the story the sultan of Egypt ceded to the emperor all these territories including the city of Jerusalem, which was fantastically unusual."

Before signing the agreement, the emperor fortified the castle of Jaffa, and, it now appears, left in its walls two inscriptions, one in Latin and the other in Arabic. The small bit of the Latin inscription that remains was previously attributed to Frederick II, Sharon said.

In the Arabic inscription, Frederick II refers to himself as the king of Jerusalem, suggesting that although Pope Gregory IX had excommunicated him for not starting the Crusade earlier, Frederick II came to power with consent from the sultan, Sharon said.

"It was all diplomacy, which is very interesting," Sharon said, adding, "Although he got the home of Jerusalem, what he didn't get or want was a temple mount, he thought it was a Muslim sanctuary and should remain in the Muslim hands."

As for Frederick II's colorful personality, Sharon said that in addition to opening a zoo and a university, the ruler had a harem that included a Muslim woman.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.