Sperm don't swim anything like we thought they did, new study finds

New research upends more than three centuries of beliefs about how sperm move.

Under a microscope, human sperm seem to swim like wiggling eels, tails gyrating to and fro as they seek an egg to fertilize.

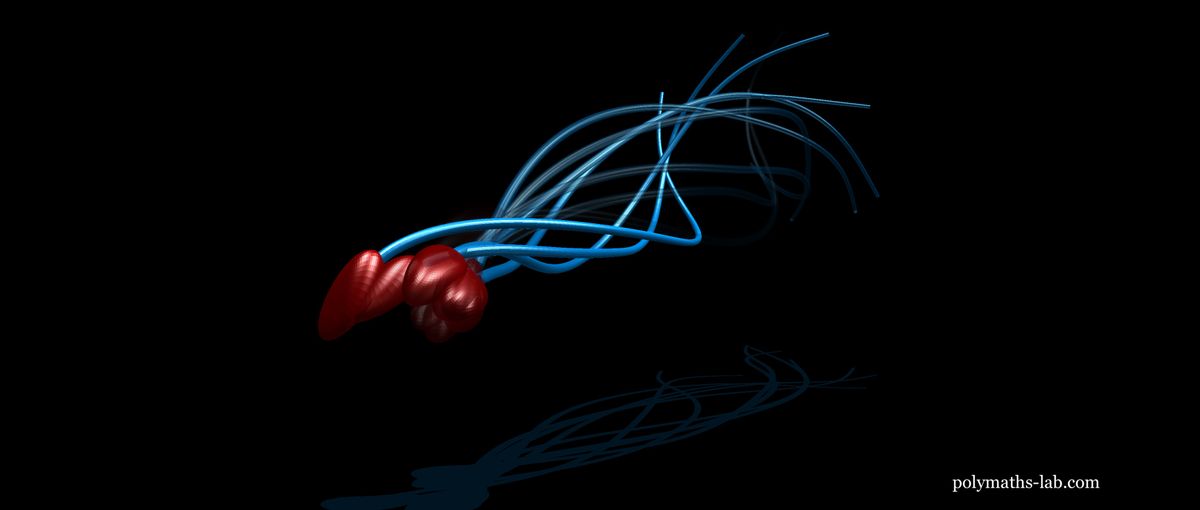

But now, new 3D microscopy and high-speed video reveal that sperm don't swim in this simple, symmetrical motion at all. Instead, they move with a rollicking spin that compensates for the fact that their tails actually beat only to one side.

"It's almost like if you're a swimmer, but you could only wiggle your leg to one side," said study author Hermes Gadêlha, a mathematician at the University of Bristol in the U.K. "If you did this in a swimming pool and you only did this to one side, you would always swim in circles. … Nature in its wisdom came [up] with a very complex, ingenious way to go forward."

Related: Sexy swimmers: 7 facts about sperm

Strange swimmers

The first person to observe human sperm close up was Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, a Dutch scientist known as the father of microbiology. In 1677, van Leeuwenhoek turned his newly developed microscope toward his own semen, seeing for the first time that the fluid was filled with tiny, wiggling cells.

Under a 2D microscope, it was clear that the sperm were propelled by tails, which seemed to wiggle side-to-side as the sperm head rotated. For the next 343 years, this was the understanding of how human sperm moved.

"[M]any scientists have postulated that there is likely to be a very important 3D element to how the sperm tail moves, but to date we have not had the technology to reliably make such measurements," said Allan Pacey, a professor of andrology at the University of Sheffield in England, who was not involved in the research.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new research is thus a "significant step forward," Pacey wrote in an email to Live Science.

Gadêlha and his colleagues at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México started the research out of "blue-sky exploration," Gadêlha said. Using microscopy techniques that allow for imaging in three dimensions and a high-speed camera that can capture 55,000 frames per second, they recorded human sperm swimming on a microscope slide.

"What we found was something utterly surprising, because it completely broke with our belief system," Gadêlha told Live Science.

Related: The 7 biggest mysteries of the human body

The sperm tails weren't wiggling, whip-like, side-to-side. Instead, they could only beat in one direction. In order to wring forward motion out of this asymmetrical tail movement, the sperm head rotated with a jittery motion at the same time that the tail rotated.The head rotation and the tail are actually two separate movements controlled by two different cellular mechanisms, Gadêlha said. But when they combine, the result is something like a spinning otter or a rotating drill bit. Over the course of a 360-degree rotation, the one-side tail movement evens out, adding up to forward propulsion.

"The sperm is not even swimming, the sperm is drilling into the fluid," Gadêlha said.

The researchers published their findings today (July 31) in the journal Science Advances.

Asymmetry and fertility

In technical terms, how the sperm moves is called precession, meaning it rotates around an axis, but that axis of rotation is changing. The planets do this in their rotational journeys around the sun, but a more familiar example might be a spinning top, which wobbles and dances about the floor as it rotates on its tip.

"It's important to note that on their journey to the egg that sperm will swim through a much more complex environment than the drop of fluid in which they were observed for this study," Pacey said. "In the woman's body, they will have to swim in narrow channels of very sticky fluid in the cervix, walls of undulating cells in the fallopian tubes, as well have to cope with muscular contractions and fluid being pushed along (by the wafting tops of cells called cilia) in the opposite direction to where they want to go. However, if they are indeed able to drill their way forward, I can now see in much better clarity how sperm might cope with this assault course in order to reach the egg and be able to get inside it," Pacey said

Sperm motility, or ability to move, is one of the key metrics fertility doctors look at when assessing male fertility, Gadêlha said. The rolling of the sperm's head isn't currently considered in any of these metrics, but it's possible that further study could reveal certain defects that disrupt this rotation, and thus stymy the sperm's movement.

Fertility clinics use 2D microscopy, and more work is needed to find out if 3D microscopy could benefit their analysis, Pacey said.

"Certainly, any 3D approach would have to be quick, cheap and automated to have any clinical value," he said. "But regardless of this, this paper is certainly a step in the right direction."

Originally published in Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.