Life's Extremes: Atheists vs. Believers

This December is chock full of "holy days," or holidays. On Dec. 25, Christians commemorate Christmas. For Jews, Hanukkah starts this year on Dec. 20 in the Western and international Gregorian calendar. Shia Muslims, meanwhile, celebrate Ashura today (Dec. 4), the 10th day of the Islamic lunar calendar's first month. Yet others in the Northern Hemisphere will party on Dec. 22 for the winter solstice, as druids might have ritualistically done so at Stonehenge in the U.K. 4,000 years ago.

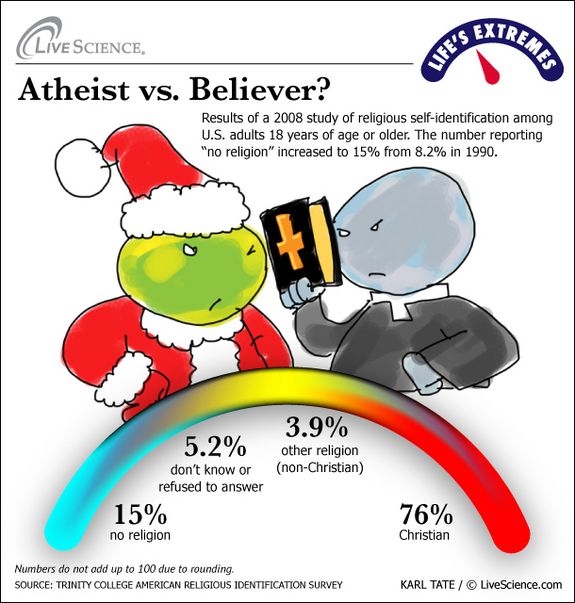

Religion, it goes without further saying, is a very popular phenomenon. In the U.S., as in much of the world, a majority of people claim to practice some form of it. According to recent surveys, around 80 percent of American adults say they belong to an organized religion.

A minority of that population takes its religion very seriously. These individuals' behaviors and attitudes are largely influenced by what is perceived to conform to their faiths' dogmas. On the opposite end, another, smaller percentage of the population thinks that religion is absolute hooey.

Psychologists, sociologists and neurologists continue to study why some gobble up religion as profound truth while others reject it as superstition.

"This whole area [of research] teaches us something about the human mind and brain," said Andrew Newberg, director of research at the Myrna Brind Center of Integrative Medicine at Thomas Jefferson University and author of "How God Changes Your Brain" (Ballantine Books, 2009).

"There are a lot of philosophical and theological implications of this work and about how we understand the world," Newberg added.

Religion's broad appeal

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Virtually every society throughout history has worshipped and feared supernatural deity figures, from animal and ancestral spirits to Olympian gods and goddesses to Jesus and Satan.

Religion in some fashion has emerged, and oftentimes independently, "in every culture and society going back 100,000 years when the human brain began to form and expand," said Newberg. This fact has led some researchers to suggest that a tendency toward religion is "built" into our brains, perhaps as a byproduct of the development of complex cognitive abilities. [10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain]

Whatever their source, religious sentiments remain strong in the 21st century. "There are more religious folk than non-religious folk in most of the world," said Barry Kosmin, director of the Institute for the Study of Secularism in Society and Culture at Trinity College and co-principal investigator of the American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS). "Religion is the normative position." [The World's Top Religions (Infographic)]

Identifying the holy-noers ….

Yet some individuals buck this trend. According to the latest ARIS and the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life data, 15 percent and 16 percent, respectively, of people in the U.S. are unaffiliated with or indifferent to organized religions.

Of that group, just 0.7 percent in ARIS and 1.6 percent in Pew identify themselves as atheists. According to other survey questions, the overall percentage of those who not believe in gods is higher at about 7 percent, Kosmin said, but few opt for the term "atheist," which some see as having negative connotations. [Why Atheists Celebrate Christmas]

Slightly larger slivers say they are agnostics (unsure or think that gods are unknowable), at 0.9 percent in ARIS and 2.4 percent in Pew.

…. and holy-rollers

At the other extreme the religious zealots, naturally, do not self-identify as such. Surveys have shown, however, that about a fifth of Americans describe themselves as extremely religious, Kosmin said.

He also pointed out that attitudes revealed by the University of Chicago's detailed General Social Survey can help get at the percentages of those with extremely religiously motivated views.

For starters, about a quarter of the U.S. population attends a place of worship (primarily a Christian church) weekly. Within this churchgoing group, just over half (53 percent) believe in the Bible's inerrancy; that is, they believe that this collection of ancient texts is the literal word of the Christian god. Another 43 percent are opposed to abortion even in the case of rape, Kosmin noted, and some 79 percent are opposed to the acceptance of homosexuality.

The most zealous of the zealous, of course, would be those rare individuals who turn to violence by shooting abortion clinic doctors or becoming suicide bombers.

God's country

To an extent, atheists and enthusiastic believers are products of their environment, so to speak. Growing up in secular or highly religious families and communities can strongly influence an individual's world view.

Geographically in the U.S, the affluent West Coast and Northeast are well-known for their higher-than-average levels of godlessness, and are home to a disproportionate number of atheists. In contrast, poorer states, especially those in the "Bible Belt" of the southeastern and south-central U.S., have more zealotry.

"Regional cultures are strong," said Kosmin. "It's the Vermonts and Oregons of the world where you find more atheists and more secular folk, and it's Alabama and Mississippi, the Bible Belt where you find more of the religious people."

Religion and lack thereof in the brain

Beyond regional influences, brain conditioning may also move an individual out of the mainstream of mild and moderate religiosity into atheism or zealotry.

Newberg and other researchers have seen changes, for example, in the brains of those who meditate or pray frequently. Imaging studies have revealed that the brain's frontal lobes, which are activated during prayer, increase in activity and thickness in people. The thalamus, a key relay that integrates sensory information, also showed changes in people who prayed for as little as 12 minutes a day for two months, Newberg explained.

"There's this saying, 'the neurons that fire together wire together,'" said Newberg. "The more you believe in it, the more that belief becomes your reality."

For both non-religious and religious people, then, reinforcement of a set of beliefs modifies the brain to accept information supportive of that system and reject information that goes against it.

Inherent brain biology as determined by genetics could play a role, too. Some findings: A proposed "god gene" could predispose gene carriers to transcendental experiences, while those people with a more prominent brain fold called the paracingulate sulcus might be better able to separate real events from imagination.

"Clearly there are bits and pieces of our biology that make us prone to religious and spiritual ideas and beliefs," said Newberg. "As with all characteristics of human beings, there's a bit of a bell curve, with some finding it very easy to believe in these things and others finding it very hard."