World's Oldest Bedding Discovered in Cave

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

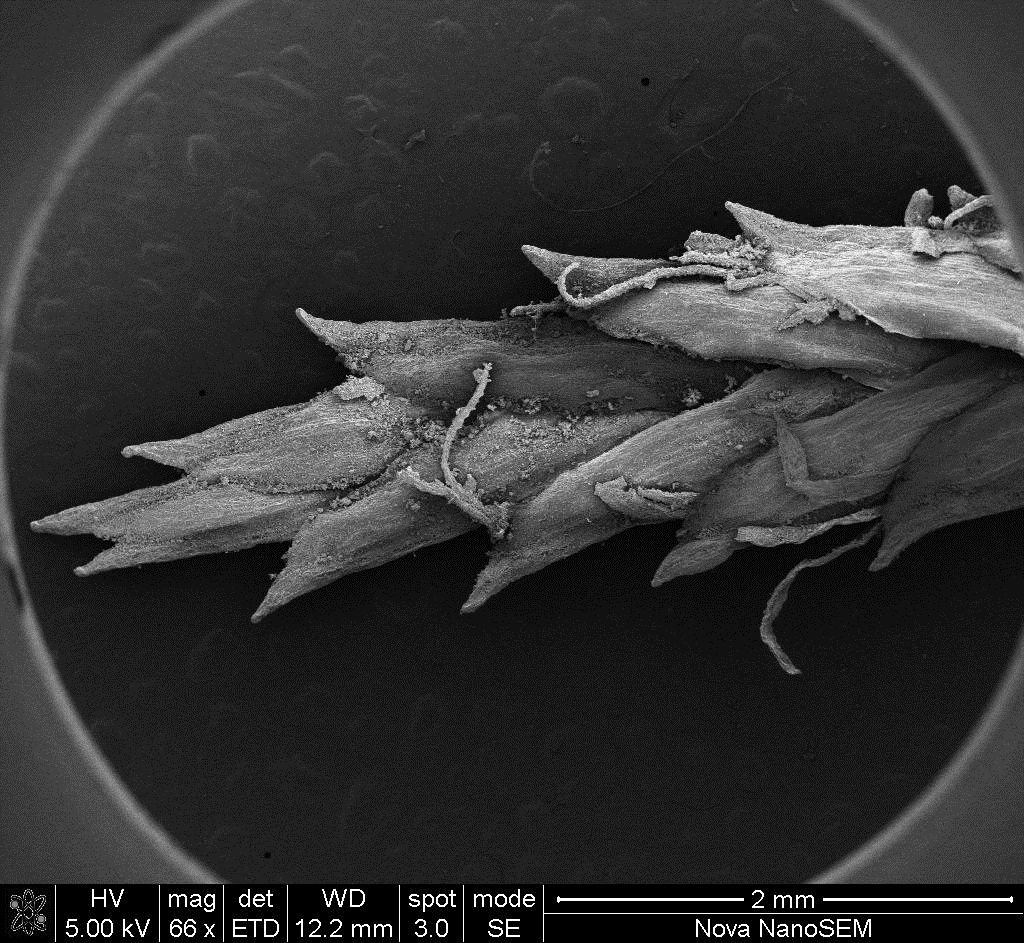

The oldest known bedding — sleeping mats made of mosquito-repellant evergreens that are about 77,000 years old — has been discovered in a South African cave.

This use of medicinal plants, along with other artifacts at the cave, helps reveal how creative these early peoples were, researchers said.

An international team of archaeologists discovered the stack of ancient beds at Sibudu, a cave in a sandstone cliff in South Africa. They consist of compacted stems and leaves of sedges, rushes and grasses stacked in at least 15 layers within a chunk of sediment 10 feet (3 meters) thick.

"The inhabitants would have collected the sedges and rushes from along the uThongathi River, located directly below the site, and laid the plants on the floor of the shelter,"said researcher Lyn Wadley, an archaeologist at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa.

The oldest mats the scientists discovered are approximately 50,000 years older than other known examples of plant bedding. All told, these layers reveal mat-making over a period of about 40,000 years.

"The preservation of material at Sibudu is really exceptional," said researcher Christopher Miller, a geoarchaeologist at the University of Tübingen in Germany. [See Photos of the Ancient Beds]

Many of the plant remains are species of Cryptocarya, evergreen plants that are used extensively in traditional medicines. The beds appeared to be mostly composed of river wild-quince (Cryptocarya woodii), whose crushed leaves emit insect-repelling scents.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The selection of these leaves for the construction of bedding suggests that the early inhabitants of Sibudu had an intimate knowledge of the plants surrounding the shelter, and were aware of their medicinal uses," Wadley said. "Herbal medicines would have provided advantages for human health, and the use of insect-repelling plants adds a new dimension to our understanding of behavior 77,000 years ago."

Microscopic analysis of the bedding suggested the inhabitants repeatedly refurbished the mats. Starting about 73,000 years ago, the site's inhabitants apparently also burned the bedding regularly, "possibly as a way to remove pests," Miller said. "This would have prepared the site for future occupation and represents a novel use of fire for the maintenance of an occupation site."

These mats were used for more than just slumber. "The bedding was not just used for sleeping, but would have provided a comfortable surface for living and working," Wadley said.

Beginning about 58,000 years ago, the layers of bedding at the site became more densely packed, and the number of hearths and ash dumps rose dramatically as well. The archaeologists believe this is evidence of a growing population, perhaps corresponding with other population changes within Africa at the time. By approximately 50,000 years ago, modern humans began expanding out of Africa, eventually replacing now-extinct forms of humans in Eurasia, including the Neanderthals.

The age of the oldest mats are roughly contemporaneous with other South African evidence of modern human behavior, such as the use of perforated shell beads, sharpened bone points likely used for hunting, bow and arrow technology, the use of snares and traps and the production of glue for attaching handles onto stone tools.

"These discoveries show the creativity and diversity of behavior that these early humans practiced," Miller told LiveScience.

Wadley, Miller and their colleagues detailed their findings in the Dec. 9 issue of the journal Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus