Woolly Mammoths Could Be Cloned Someday, Scientist Says

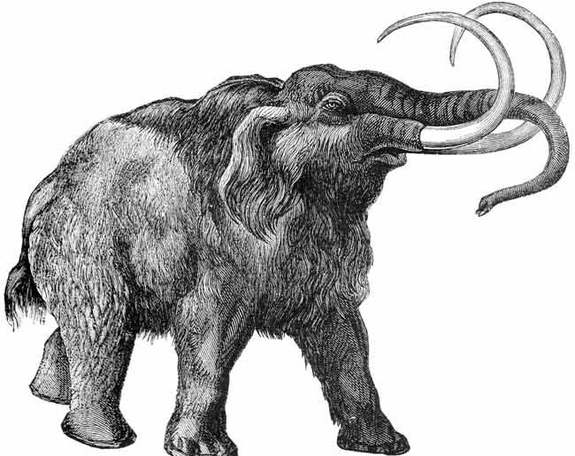

Woolly mammoths — shaggy, long-extinct relatives of modern elephants — could be easier to clone than one might think, researchers say.

Still, even if any such efforts succeed, they might take decades to accomplish, not the five years in which scientists from Russia and Japan reportedly have said they can achieve it.

Woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius) wandered the planet for roughly 250,000 years, ranging from Europe to Asia to North America. Nearly all of these giants vanished from Siberia by about 10,000 years ago, although dwarf mammoths survived on Wrangel Island in the Arctic Ocean until 3,700 years ago.

Scientists regularly conduct research on the DNA of these shaggy giants, extracting it from tusks, bone and teeth. With all this genetic material on hand, there lies the distinct possibility mammoths might be cloned one day.

"Recreating extinct organisms is definitely within reason," researcher Hendrik Poinar, an evolutionary geneticist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada, told LiveScience. "It will be possible."

Still, it may take closer to 20 to 50 years, if at all, Poinar noted.

Resurrecting extinct animals

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Extinct animals have been resurrected by cloning before, albeit briefly. Scientists in Spain had cloned a Pyrenean ibex (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica), a subspecies of wild goat also known as the bucardo, which went extinct in 2000.

The last bucardo died after she was struck on the head by a falling branch. However, researchers managed to take DNA from skin samples taken from this female goat beforehand, which they injected into domestic goat eggs emptied of their original genetic material to create viable embryos.

This bucardo clone died soon after birth due to lung defects, dooming the goat to a second extinction. Abnormalities are common in cloning — developmental errors might creep in during the massive chemical reprogramming the DNA has to undergo to revert it to an embryonic state, or during the cultivation or handling of the embryos. Also, if the environment in which an embryo develops is not a close match to what it should be, problems can occur during pregnancy.

Genes from extinct animals are occasionally revived in live animals as well — for instance, genetic material extracted from the extinct Tasmanian tiger proved functional in mice.

Woolly mammoth clones

So what of the woolly mammoth? There may be enough DNA to clone the animal, since plenty of woolly mammoth bodies have been discovered over the years, some of which still have frozen meat on their bones. The woolly mammoth also went extinct relatively recently, which holds out the possibility that some material is pristine enough for cloning. Genetic material from fossil dinosaurs, on the other hand, is likely far too old and damaged for successful cloning of the extinct reptiles. [Can We Make Jurassic Park Yet?]

So are there surrogate mothers close enough to woolly mammoths to birth any clones?

"We know African and Asian elephants can interbreed, and they're separated by 5 million to 6 million years," Poinar said. "Asian elephants are actually closer to mammoths than they are to African elephants — mammoths split from Asian elephants after Asian elephants split from African elephants — so if living elephants can interbreed, perhaps an Asian elephant can host a mammoth embryo."

In fact, news reports suggest the Japanese and Russian scientists say they plan to extract a nucleus from the bone marrow of a woolly-mammoth thigh bone, though others have warned the marrow cells are likely not intact. Then, the researchers have said they will insert that nucleus into the egg of a modern elephant.

Mammoth hurdles?

Still, there are many technical hurdles to any such cloning.

"If — and only if — they find intact cells, they might be lucky at five to 10 years," Poinar said. "But I highly doubt they will find intact cells."

Instead, any efforts to resurrect mammoths will likely involve weaving bits and pieces of DNA into artificial chromosomes. (Each of the body's chromosomes, held in the nucleus of animal and plant cells, contains an extremely long molecule of DNA.)

"Elephants have 50 to 60 chromosomes, far more than us, so replicating all of those will be challenging," Poinar said. "There you are looking 20 to 50 years, I would say."

There are also ethical concerns. Even if scientists do successfully clone mammoths, it does not mean they have resurrected a viable species — if the population is small, then such a small genetic pool could be very susceptible to disease and other environmental factors.

"There is no good scientific reason to bring back an extinct species," Poinar said. "Why would one bring them back? To put them in a theme park? Doesn't seem like a good use of taxpayer dollars to me. Simply studying their evolution, which can be done from old fossil bones, seems far more satisfying to me — but that's just me."

"Someone is going to do this eventually, ethics or no," Poinar said. "And it might be expensive to try and clone mammoths, but how many people would visit the zoo to see one?"