Earth Makes Closest Approach to Sun of the Year

If the sun appears a bit more intense than normal to you this week, you're not seeing things. The Earth has just made its closest approach to our nearest star for the year.

The orbital milestone is known as "perihelion," and it marks the time when the distance between the Earth and the sun is at its smallest. The event occurs every year in early January, and in 2012 it took place Wednesday, Jan. 4 at 8 p.m. EST (or Jan. 5 at 0100 GMT, depending on your time zone).

On average, the Earth orbits the sun at a distance of about 93 million miles (150 million kilometers). This distance is known as 1 astronomical unit (AU), and it serves as a yardstick for distances to other planets in our solar system. Mars, for example, is about 1.5 AU from the sun, while Jupiter is about 5.2 AU from the star.

But like the other planets in our solar system, the Earth's orbit is not a perfect circle. Instead, it is slightly elliptical — or oval-shaped — meaning it has a closest point to the sun (perihelion) and a farthest point (which is known as aphelion).

During the 2012 perihelion, the Earth was about 91.3 million miles (147 million km) from the sun, or about 0.983 AU. The Earth will reach aphelion on July 5. At that time, our planet will be about 94.5 million miles (152 million km) — or 1.017 AU — from the sun.

The difference between the two extremes of Earth's orbit is just over 3 million miles (5 million km). In January, the sun can appear to shine about 7 percent more intensely than it does in July during aphelion, according to NASA descriptions. [Top 10 Views of Earth from Space]

If you live in the Northern Hemisphere, the fact that Earth is closest to the sun during the cold winter season may be confusing, but there is an explanation.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Earth's changing seasons are actually determined by our planet's tilt on its axis, not its distance from the sun. Our planet spins on an axis that is tilted about 23.5 degrees from vertical. This tilts the Northern Hemisphere away from the sun during the northern winter and toward the sun during the northern summer.

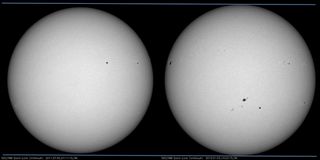

The Earth's closest approach to the sun each year has effects that can reach all the way into space. Several space telescopes keep constant watch on the sun to study its solar storm and flare activity. Since some of those probes are stationed near Earth or its orbit, scientists had to take into account the variations in the sun's apparent size when the planet reaches its perihelion and aphelion.

One of those spacecraft is NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), which has several cameras to record high-definition videos of the sun. SDO mission scientists said Earth's perihelion played a big role in choosing the spacecraft's digital cameras (known as charged coupled devices, or CCDs).

"Why do we care? Because SDO takes a lot of pictures of the sun. At perihelion they appear a little bigger than they do at aphelion in July," mission scientists explained in a blog post. "When we designed the instruments on SDO we had to make sure the largest appearance of the sun would fit on the CCDs."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Most Popular