Omega-3s Vital for Sperm Health

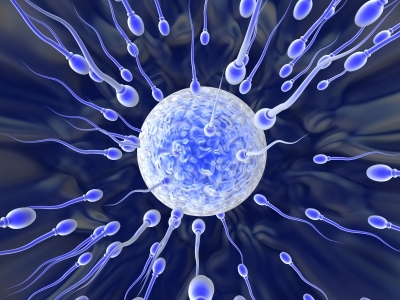

A fatty acid found in fish is critical to turning dysfunctional round-headed sperm into strong swimmers with cone-shaped heads packed with egg-opening proteins, a new study finds.

Docosahexnoic acid, also called DHA, is an important omega-3 fatty acid involved in eye and brain development; recent studies in mice have implicated it in male fertility as well.

"DHA is high in the testes and brain, but until this it was not well understood what it does in these tissues," study researcher Manabu Nakamura, of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, told LiveScience. "About three years ago we created the knockout mouse, which isn't able to make its own DHA, and we learned that DHA is really essential for sperm formation." In the new study, Nakamura and colleagues figured out why DHA is so critical to healthy sperm.

Like other omega-3s, DHA is found in fish, especially cold-water oceanic fish, and algae. For fish-fearing wannabe fathers, seafood and algae aren't our only source of the nutrient; your body can also make DHA from other omega-3 acids.

Sterile swimmers

In their past work, Nakamura and colleagues studied mice without a DHA-synthesizing enzyme, finding that if these mice also didn't get DHA in their diet, the males were infertile. Fertility returned when their diet was supplemented with the fatty acid. [What Are Omega-3 Fatty Acids?]

Following these findings, in the new study the team looked at how sperm develops in DHA-deficient mice. The researchers determined that DHA plays a role in the formation of a structure called the acrosome on the head of the sperm. The acrosome is a pointy caplike structure containing enzymes that break through the egg's outer layers, enabling the sperm to fertilize it.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The acrosome on top of this cone head is gigantic, it is a large sack containing lots of enzymes," Nakamura said. "When the sperm meets the egg, the acrosome bursts and it releases enzymes and helps the sperm penetrate into the egg."

The acrosome forms when many little bubbles of membrane (called vesicles) fuse together inside the sperm-to-be. These bubbles hold the enzymes the sperm needs to penetrate and fertilize the egg. When they come together they all fuse into one long sheet of membrane in the front of the sperm, forming a cap, the acrosome.

Without DHA, this membrane fusion doesn't happen. If the vesicles don't fuse, the acrosome doesn't get made and sperm maturation halts. At this point, the researchers only see sperm with round heads, not the cone-shaped heads of healthy sperm.

DHA deficiency

Because humans and other mammals are able to make their own DHA from other fatty acids, DHA deficiency isn't very common. But, if that DHA-synthesizing enzyme is defective, it could lead to problems with infertility. Low blood levels of DHA have been linked to decreased fertility in the past; a DHA-rich diet could clear up these infertility problems.

"As long as this endogenous [within the body] system is working fine, humans can synthesize enough DHA in their bodies if they have the precursor," Nakamura said. "But some groups [of people] may have a decreased ability to synthesize DHA. In this case the dietary supplements may help."

In the long term, the acrosome could be a target for a male birth control pill, if the acrosome formation could be switched on and off, but the researchers aren't studying that yet. They are, however, looking to other parts of the body to see how the DHA deficiency affects brain and eye function. It could act in very similar ways, by facilitating vesicle fusion, in other parts of the body.

The study, announced this week (Jan. 9), is published in the October 2011 issue of the journal Biology of Reproduction.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.