When did Democrats and Republicans switch platforms?

When did Democrats and Republicans switch platforms, changing their political stances — and why? The Republicans used to favor big government, while Democrats were committed to curbing federal power.

The Republican and Democratic political parties of the United States didn't always stand for what they do today. The more liberal Democrats and the right-wing Republicans each have a defined set of belief systems, but these were once very different. So when did Democrats and Republicans switch platforms? And why?

First Republican and Democratic platforms

During the 1860s, Republicans, who dominated northern states, orchestrated an ambitious expansion of federal power, described by the Free Dictionary as "a system of government in which power is divided between a central authority and constituent political units." This helped to fund the transcontinental railroad, the state university system and the settlement of the West by homesteaders, and instating a national currency and protective tariff. The Democrats, who dominated the South, opposed those measures. Indeed, according to the author George McCoy Blackburn ("French Newspaper Opinion on the American Civil War," (Greenwood Press, 1997) the French newspaper Presse stated that the Republican Doctrine at this time was "The most Liberal in its goals but the most dictatorial in its means."

Reconstruction Era to the New Deal

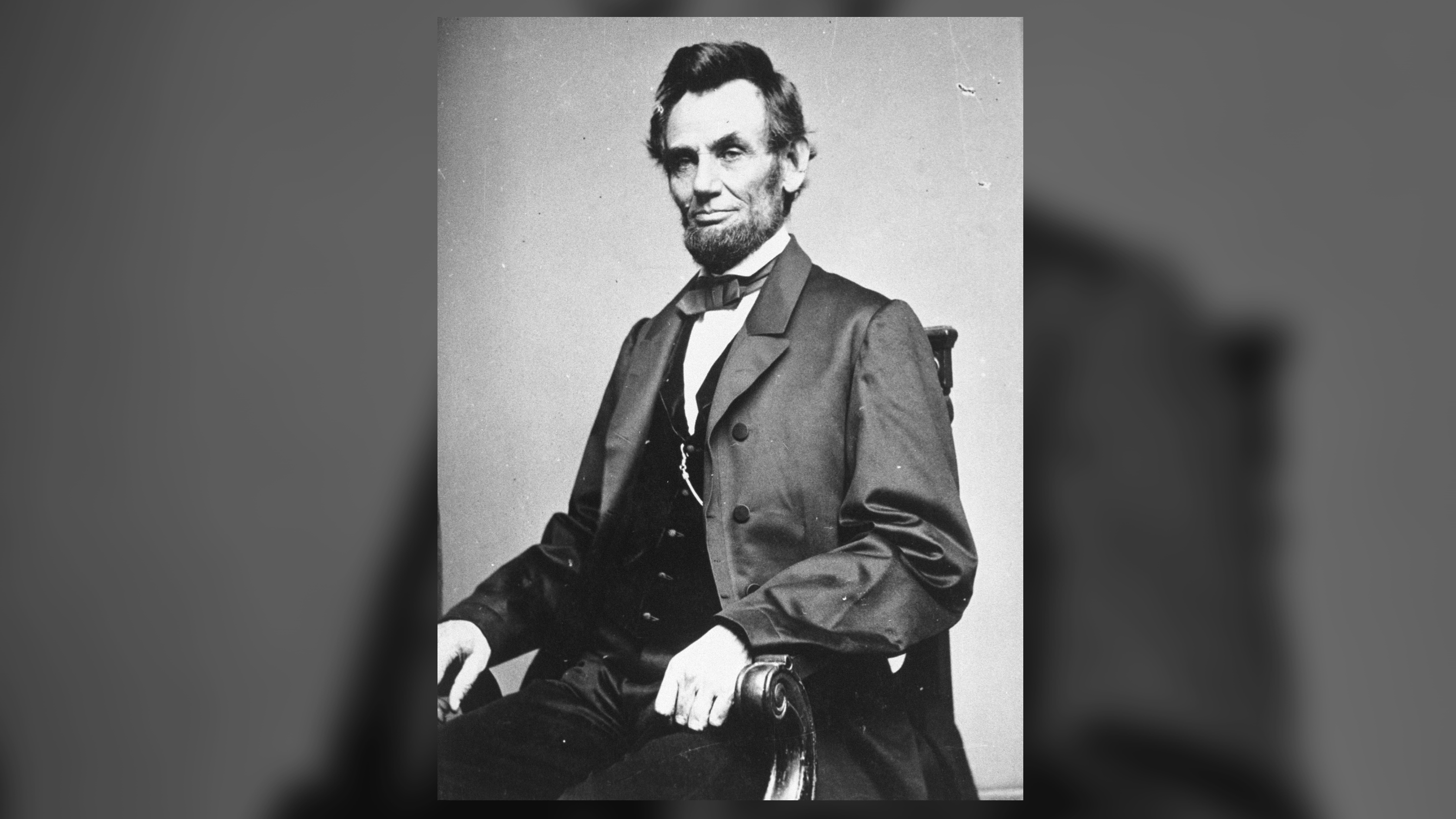

After the United States triumphed over the Confederate States at the end of the Civil War, and under President Abraham Lincoln, Republicans passed laws that granted protections for Black Americans and advanced social justice (for example the Civil Rights Act of 1866 though this failed to end slavery). Again Democrats largely opposed these apparent expansions of federal power.

Sounds like an alternate universe? Fast forward to 1936.

Democratic President Franklin Roosevelt won reelection that year on the strength of the New Deal. This was a set of reforms designed to help remedy the effects of the Great Depression, which the FDR Presidential Library and Museum described as: "a severe, world -wide economic disintegration symbolized in the United States by the stock market crash on "Black Thursday," October 24, 1929." The reforms included regulation of financial institutions, the founding of welfare and pension programs, infrastructure development and more. It was these measures that ensured Roosevelt won in a landslide against Republican Alf Landon, who opposed these exercises of federal power.

So, sometime between the 1860s and 1936, the (Democratic) party of small government became the party of big government, and the (Republican) party of big government became rhetorically committed to curbing federal power.

How did party switch happen?

Eric Rauchway, professor of American history at the University of California, Davis, pins the transition to the turn of the 20th century, when a highly influential Democrat named William Jennings Bryan (best known for negotiating a number of peace treaties at the end of the First World War, according to the Office of the Historian) blurred party lines by emphasizing the government's role in ensuring social justice through expansions of federal power — traditionally, a Republican stance.

But Republicans didn't immediately adopt the opposite position of favoring limited government.

Related: 7 great congressional dramas

"Instead, for a couple of decades, both parties are promising an augmented federal government devoted in various ways to the cause of social justice," Rauchway wrote in an archived 2010 blog post for the Chronicles of Higher Education. Only gradually did Republican rhetoric drift toward the counterarguments. The party's small-government platform cemented in the 1930s with its heated opposition to Roosevelt’s New Deal.

But why did Bryan and other turn-of-the-century Democrats start advocating for big government?

Big government

According to Rauchway, they, like Republicans, were trying to win the West. The admission of new western states to the union in the post-Civil War era created a new voting bloc, and both parties were vying for its attention.

Related: Busted: 6 Civil War myths

Democrats seized upon a way of ingratiating themselves to western voters: Republican federal expansions in the 1860s and 1870s had turned out favorable to big businesses based in the northeast, such as banks, railroads and manufacturers, while small-time farmers like those who had gone west received very little.

Both parties tried to exploit the discontent this generated, by promising the general public some of the federal help that had previously gone to the business sector. From this point on, Democrats stuck with this stance — favoring federally funded social programs and benefits — while Republicans were gradually driven to the counterposition of hands-off government.

From a business perspective, Rauchway pointed out, the loyalties of the parties did not really switch. "Although the rhetoric and to a degree the policies of the parties do switch places," he wrote, "their core supporters don't — which is to say, the Republicans remain, throughout, the party of bigger businesses; it's just that in the earlier era bigger businesses want bigger government and in the later era they don't."

In other words, earlier on, businesses needed things that only a bigger government could provide, such as infrastructure development, a currency and tariffs. Once these things were in place, a small, hands-off government became better for business.

Originally published on Live Science on Sept. 24, 2012. This article was updated on Oct. 17, 2022.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.

- Callum McKelvieFeatures Editor