Why It Took So Long to Invent the Wheel

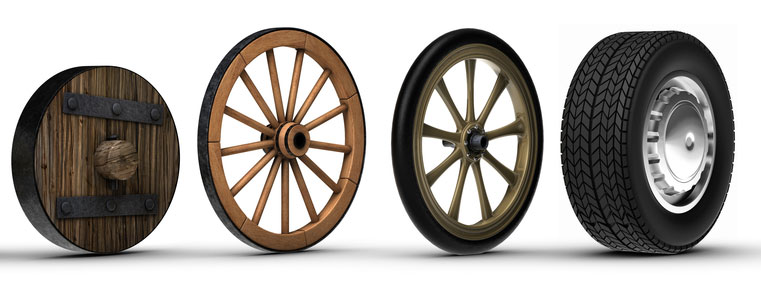

Wheels are the archetype of a primitive, caveman-level technology. But in fact, they're so ingenious that it took until 3500 B.C. for someone to invent them. By that time — it was the Bronze Age — humans were already casting metal alloys, constructing canals and sailboats, and even designing complex musical instruments such as harps.

The tricky thing about the wheel is not conceiving of a cylinder rolling on its edge. It's figuring out how to connect a stable, stationary platform to that cylinder.

"The stroke of brilliance was the wheel-and-axle concept," said David Anthony, a professor of anthropology at Hartwick College and author of "The Horse, the Wheel, and Language" (Princeton, 2007). "But then making it was also difficult."

To make a fixed axle with revolving wheels, Anthony explained, the ends of the axle had to be nearly perfectly smooth and round, as did the holes in the center of the wheels; otherwise, there would be too much friction between these components for the wheels to turn. Furthermore, the axles had to fit snugly inside the wheels' holes, but not too snugly — they had to be free to rotate. [What Makes Wheels Appear to Spin Backward?]

The success of the whole structure was extremely sensitive to the size of the axle. A thick axle would generate too much friction, while narrow one would reduce friction but would also be too weak to support a load. "They solved this problem by making the earliest wagons quite narrow, so they could have short axles, which made it possible to have an axle that wasn't very thick," Anthony told Life's Little Mysteries.

The sensitivity of the wheel-and-axle system to all these factors meant that it could not have been developed in phases, he said. It was an all-or-nothing structure.

Whoever invented it must have had access to wide slabs of wood from thick-trunked trees in order to carve large, round wheels. They also needed metal tools to chisel fine-fitted holes and axles. And they must have had a need for hauling heavy burdens over land. According to Anthony, "It was the carpentry that probably delayed the invention until 3500 B.C. or so, because it was only after about 4000 B.C. that cast copper chisels and gouges became common in the Near East."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The invention of the wheel was so challenging that it probably happened only once, in one place. However, from that place, it seems to have spread so rapidly across Eurasia and the Middle East that experts cannot say for sure where it originated. The earliest images of wheeled carts have been excavated in Poland and elsewhere in the Eurasian steppes, and this region is overtaking Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq) as the wheel's most likely birthplace. According to Asko Parpola, an Indologist at the University of Helsinki in Finland, there are linguistic reasons to believe the wheel originated with the Tripolye people of modern-day Ukraine. That is, the words associated with wheels and wagons derive from the language of that culture.

Parpola thinks miniature models of wheeled wagons, which are commonly found in the Eurasian steppes, likely predated human-scale wagons. "It is … striking that so many models were made in the Tripolye culture. Such models are often thought to have been children's toys, but it seems more likely to me that they were miniature counterparts of real things," he said. "The primacy of the miniature models is suggested by the fact that wheeled images of animals even come from native Indian cultures of Central America, where real wheels were never made."

Toys or not, those popular models of old have their counterparts in today's Hot Wheels and miniature fire trucks. Who appreciates wheeled vehicles more fully than babies and toddlers? Their almost universal fascination with the way tiny vehicles can be rolled along the floor, and the joy they derive from transportation in life-size ones, calls attention to the remarkable ingenuity of the wheel.

Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover. Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries, then join us on Facebook.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.