How Poverty, False Promises, Fuel Illegal Organ Trafficking

What would persuade you to sell a kidney to a stranger? For the 33 Bangladeshi kidney sellers interviewed by anthropologist Monir Moniruzzaman, the answer was simple: poverty. An illegal organ trade in Bangladesh connects wealthy transplant seekers with poor people enticed, often with false promises, to sell parts of their bodies.

Moniruzzaman uses the phrase "bioviolence" to describe the exploitation he found during his research. He linked it to the history of medical exploitation of the disenfranchised, from the Tuskegee syphilis studies, in which treatment was withheld from black study subjects, to the surrogacy market in which foreigners hire wombs in India to carry their babies. [7 Absolutely Evil Medical Experiments]

Moniruzzaman, an assistant professor in anthropology at Michigan State University, has published a description of his work in Bangladesh in the current issue of the journal Medical Anthropology Quarterly, and he is working on a book examining the violence, exploitation, and ethics of organ trafficking. LiveScience caught up with Moniruzzaman recently to talk about the prevalence of illegal organ trafficking and the stories of those involved.

Here are highlights of the interview:

How much does a Bangladeshi kidney sell for?

The average quoted price is $1,500. The market, it started more than 10 years before, and the kidneys' price was higher and it has gradually dropped. After donation, post transplantation, the poor Bangladeshis receive different amounts. In one case, a poor Bangladeshi, a 23-, 24-year-old boy, received only $600, and he was promised $1,600 to $1,700. In my study, 81 percent of the sellers didn't receive money they were promised.

You set out to talk with people about their experiences selling a body part and you ultimately interviewed 33 kidney sellers. How did you find these people?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

At the beginning, the first four months I couldn't find anybody. Even Bangladeshi doctors claimed this doesn’t happen within their country. I talked to recipients in the hospital. All of the recipients mentioned they got the organs from family members. When I asked to talk with them [the family members], they came up with different stories: "We aren't in touch with the donor," "The donor lives in a remote area."

Then I met a recipient, I found him through a friend of mine, he's a professor at a Bangladeshi university. I called him and introduced myself and said I am at a university in North America, I am doing some research. He understood what research means and he opened up. Following that, I interviewed the person whose organ he received, the seller. But then I couldn’t find other sellers.

I had to go through a broker [who acts as an intermediary for the sale], that is the only way I had to find other sellers. I approached four brokers and one of them, I convinced him. That is the way I found those 33 sellers. So it was extremely challenging.

You write that many sellers don't even know what a kidney is when they first see newspaper advertisements seeking a "donation." Going in, what does a seller know about the transaction?

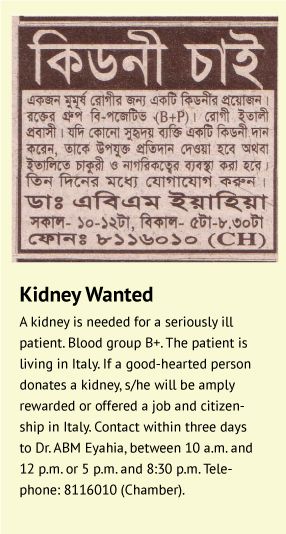

These people live in a dire state of poverty. Many of these people have debt; the debt is accumulating every day with high interest. Or they are jobless or trying to find a way to go abroad to change their economic conditions. The newspaper ads come into their hands and most of them don’t know what "kidney" means. They are tempted by the promise that appeared in the newspaper ad.

I collected close to 1,300 newspaper ads. Many promise a reward or compensation, including travel to countries like the U.S. or Italy. These are likely false promises, because the sellers cannot guarantee visas.

Brokers tell the story of "the sleeping kidney": One kidney sleeps, the other kidney works, so people don’t need two kidneys. Doctors turn on the sleeping kidneys and extract the old kidney and give it to the recipient.

The whole recruitment, it's like a package of deception, manipulating these poor Bangladeshis.

There is a constant battle between hope and fear. So, basically, it is a constant negotiation. Their only source of getting information is from the broker or recipient, but the recipient and the broker don't want to inform them of the risks involved and the procedure. Sometimes the sellers ask the doctors and the doctors say a kidney operation is a routine procedure; it saves a life and there is no harm to the donors.

Your article mentions that sellers often receive more-invasive surgery than necessary because buyers want to avoid the extra $200 cost.

All sellers except one had a long scar about 15 to 20 inches long [38.1 to 50.8 centimeters] on their bodies. They did not know that if the brokers or recipients paid $200 more, the surgeons could have used laparoscopic surgery, which requires the incision as small as 3 or 4 inches [7.6 to 10.2 centimeters].

In the article, you describe many problems the sellers experience after the surgery, including physical problems like long-term back pain, an inability to pay for follow-up care, social stigma, difficulties working that aggravated their poverty, and psychological trauma. How did this play out for a few of the sellers you interviewed?

One example is Mofiz [a pseudonym for the 43-year-old owner of a tea stand]. He had to go to the recipient after the transaction to get his money. He traveled multiple times to see the recipient. Each time the recipient would pay $100, $50, and Mofiz was coming from his village and each time he was coming he was losing money. He became worried and one time he came with his wife.

As Mofiz told me the story, "My wife said she would not leave the place without getting the money. The recipient held my wife's neck and pushed her towards the wall. My wife's forehead was cut and blood started dripping from it. I caught her and placed her in a chair. The recipient's elder son closed the door and locked it. He brought a long stick and started beating me up. He threatened me that if I ever came to their place again, he would kill me. I feared for my life. He then threw 2,000 Taka [$30] at us. I did not take it at first, but he forced me to do so. They told us to leave and slammed and locked the door in our faces. We went to the train station and cursed them over the phone, saying that everything would be destroyed for them."

Mofiz was crying when he told me. He said, "I saved someone's life and in return what am I getting? They beat me up." He thought about committing suicide.

There is another, Sodrul, [also a pseudonym] a college student, he went to India with a broker and basically he realized this is a risky operation and he didn't want to do it, so he asked the broker to give his passport back so he could leave. The broker hired two Indian thugs; all three of them started beating him up and they basically forced him to go to the operating room. They told him, "Your family is not going to get your dead body back to Bangladesh."

You found that buying a kidney is not always a desperate act by recipients. Why?

There are many kidney patients who follow ethics and think of organ trafficking as an illegal, unethical act. They have access to it and they decline to take that route in life. I have deep respect for those kideny patients whose ethical integrity is intact. [Chronic Kidney Disease: Symptoms and Treatment]

What I found is many recipients in the study, they are not getting donations from family members; rather, they are getting a kidney from the market because the market is out there, so why would someone put a family member at risk? The price is $1,500, which is the price of a laptop. I even found one recipient who arranged a charitable art exhibition and a concert in 2006, and with the money she went to Pakistan and bought a kidney. I asked her husband, "Why didn't you donate a kidney and save her life rather than putting a poor person at risk?" He told me he was the only breadwinner in the family; therefore, he didn’t want to put himself and his whole family at risk. He was rationalizing his act.

Most of these transplantations occur in India, using fake passports and forged legal documents. How aware are the doctors performing these operations of what is really going on?

Of course that is the commercialization of medicine: More transplants mean more profit. These are not all Indian hospitals. There are many, many good Indian hospitals, but there are some, mostly privatized, hospitals that turn a blind eye. How come they don't know when the broker is bringing in 10 sellers at a time? There is no interview; on paper everything that is happening is a donation, but in real life, it is selling and buying.

* * *

Moniruzzaman's journal article, titled "Living Cadavers," notes the transaction can have profound effects on the sellers. Hiru, a 38-year-old Hindu seller, underwent circumcision because his recipient was a Muslim who feared doctors would realize they were not relatives during the operation. "In the post-transplant phase, Hiru was deeply worried, believing that God would not forgive him for his reckless action, as well as for not returning his body intact," Moniruzzaman writes. [8 Ways Religion Impacts Your Life]

According to Moniruzzaman, Bangladesh needs a system to allow people to donate organs after they die, called cadaveric donation, in order to stop this illegal organ trade. In the United States, people sign up to be organ donors when they get driver's licenses; however, there are still shortages. Spain has created a bigger pool of donors by adopting a presumed consent system, which makes everyone a donor automatically, with the option to opt out.

Technology may help, too, Moniruzzaman said. Stem cells, which could be used to grow new organs; bioengineering, which could result in artificial organs; and transplants from animals could all help.

"So there are ways of resolving this issue rather than exploiting these people who need the organs the most for their own physical survival," Moniruzzaman said.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Most Popular