Image Gallery: Pre-Human Species Sheds Light on Bipedalism

Human Bipedalism

Scientists discovered the foot bones of a 3.4-million-year-old pre-human species in 2009 in a part of Ethiopia known as Burtele. The bones belonged to a still unknown hominin, the researchers reported in March 2012 in the journal Nature. Particularly the big toe, which looks more similar to a gorilla's than a modern human's, is providing information about how humanity began to walk upright. The species also seems to have lived alongside Australopithecus afarensis, the first incontrovertible evidence for the presence of at least two pre-human species living at the same time and place around 3.4 million years ago.

Small foot bone

Researcher Stephanie Melillo holds the fourth metatarsal of the Burtele partial foot right after its discovery. The team found eight bones from the front half of a right foot. Such hominin fossils are rare, since they are fragile and are often destroyed in the face of carnivores and decay.

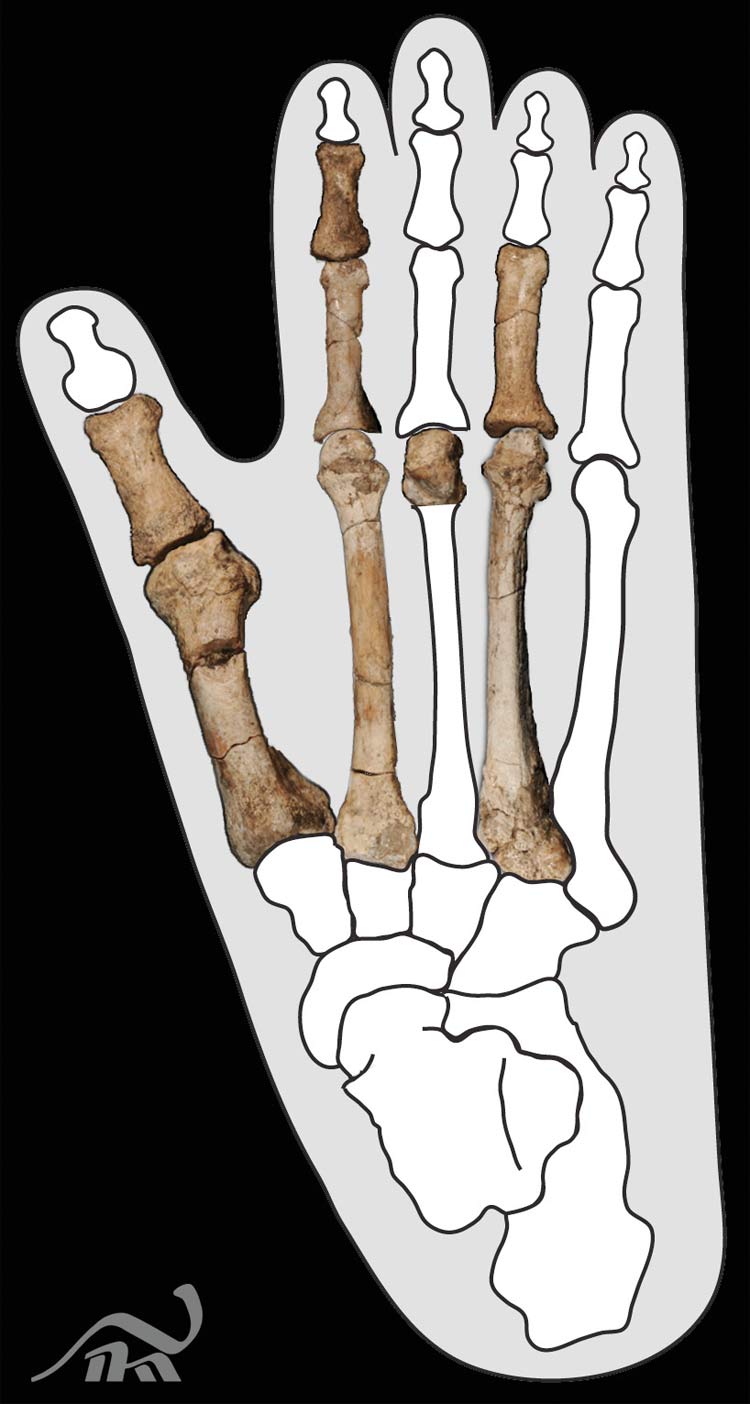

Articulated Foot

The Burtele partial foot shown after cleaning and preparation. It is shown here in its anatomically articulated form.

Fossil Fragment

Lead author Dr. Yohannes Haile-Selassie, curator of physical anthropology at The Cleveland Museum of Natural History, in the field investigating a fossil fragment from the unknown hominin.

Gorilla Feet

While the big toe of Lucy's species was lined up with the other four toes to make humanlike bipedal walking more efficient, the Burtele foot has an opposable big toe like a gorilla's (shown here). This probably made it more adept than Lucy at grasping branches and climbing trees.

Scenic Site

The fossils were discovered in the Burtele area in Ethiopia, in the northwestern part of the Woranso-Mille study area (shown here). Nowadays this area is hot and dry, with temperatures skyrocketing up to 110 degrees Fahrenheit (43 degrees Celsius). But fossils of fish, crocodiles and fish, along with features of the sediment, suggest the environment was "a mosaic of river and delta channels adjacent to an open woodland of trees and bushes," said researcher Beverly Saylor of Case Western Reserve University.

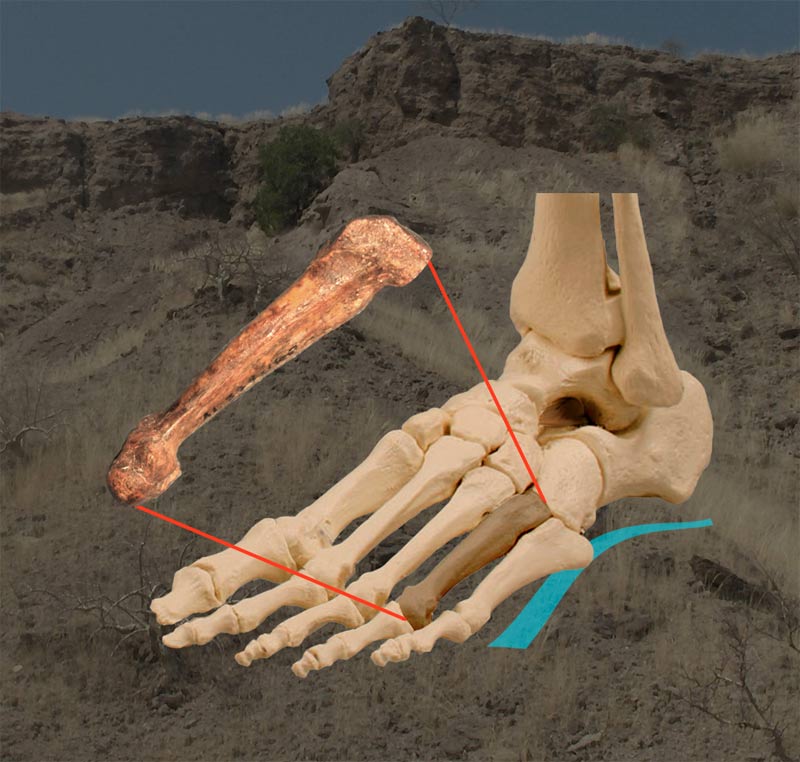

The Human Foot

Unlike Australopithecus and humans, the foot bones of the unknown hominin lacked an arch, an energy-absorbing feature of feet that helps protect bones. Shown here, the bones of a human foot showing the arched configuration and the location of the fourth metatarsal.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

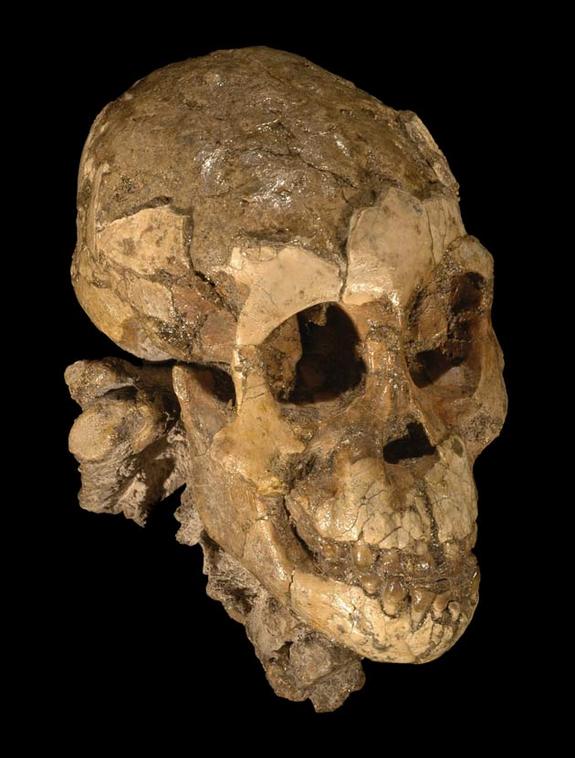

Juvenile Australopithecus

With this unknown hominin living at the same time and in the same place as Lucy's species, Australopithecus afarensis, the researchers think the two may have co-existed because they exploited different niches: Lucy would've spent time walking upright on the ground, while this newbie may have spent its time up in the trees. (Shown here, the skull of a juvenile Australopithecus afarensis, the oldest known fossil of a girl.)