Mummified Kitten Served As Egyptian Offering

Two thousand years ago, an Egyptian purchased a mummified kitten from a breeder, to offer as a sacrifice to the goddess Bastet, new research suggests.

Between about 332 B.C. and 30 B.C. in Egypt, cats were bred near temples specifically to be mummified and used as offerings.

The cat mummy came from the Egyptian Collection of the National Archeological Museum in Parma, Italy. It was bought by the museum in the 18th century from a collector. Because of how the museum acquired it, there's no documentation about where the mummy came from.

The cat mummies from this period are common, especially kittens. "Kittens, aged 2 to 4 months old, were sacrificed in huge numbers, because they were more suitable for mummification," the authors write in the paper, published in the April 2012 issue of the Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery.

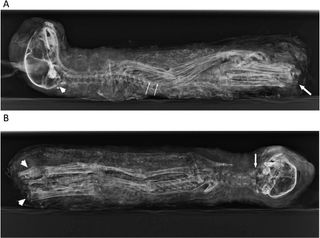

The researchers did a radiograph — similar to an X-ray — of the mummy, to see under the wrappings, finding the small cat was actually a kitten, only about 5 or 6 months old.

"The fact that the cat was young suggests that it was one of those bred specifically for mummification," study researcher Giacomo Gnudi, a professor at the University of Parma, said in a statement.

The cat was wrapped as tightly as possible, and had been placed in a sitting position before mummification, similar to the seated cats depicted in hieroglyphics from the same era. To make the cat take up as little space as possible, the embalmers fractured some of the cat's bones, including a backbone at the base of the spine to position the tail as close to the body as possible, and ribs to make the front limbs sit closer to the body.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A hole in the cat's skull may have been the cause of death, or it could have been created during the mummification process to drain the skull's contents.

"The arrangement of the mummy's wrappings is intricate, with various geometrical patterns. The eyes are depicted in black ink on small round pieces of linen bandage," the researchers write. "The cat skeleton is also complete, meaning that it is one of the most valuable types."

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter, on Google+ or on Facebook. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Most Popular