Ancient Horse Bones Tell Story of Tibetan Plateau

This story was updated at 4:24 PM EDT 4/24

A newly discovered skeleton from an ancient three-toed horse not only provides information about ancient Tibetan wildlife, but it also sheds light on the habitat and elevation of Tibet nearly 5 million years ago.

This area of the world, called the Tibetan plateau, is the youngest and highest plateau on Earth, its average elevation exceeding 14,800 feet (4,500 meters), but researchers don't know exactly when this happened. Some researchers think that 5 million years ago, the plateau was once much higher than it is today, but others think it was much lower.

More data is needed to get a good grip on when the plateau rose up, and these researchers used the fossilized horse to shed some light on the debate.

"We have an extinct horse that apparently is adapted to grasslands, these open nonwooded areas," study researcher Xiaoming Wang, of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, told LiveScience. "Therefore, in turn, it might have some implications about the environment that it came from." [High & Dry: Images of the Tibetan Plateau]

Details about the horse suggested that at the time it died, the Zanda Basin would have been about 13,000 feet (4,000 meters) above sea level, on par with the current elevation of that region of Tibet.

Horse bones

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

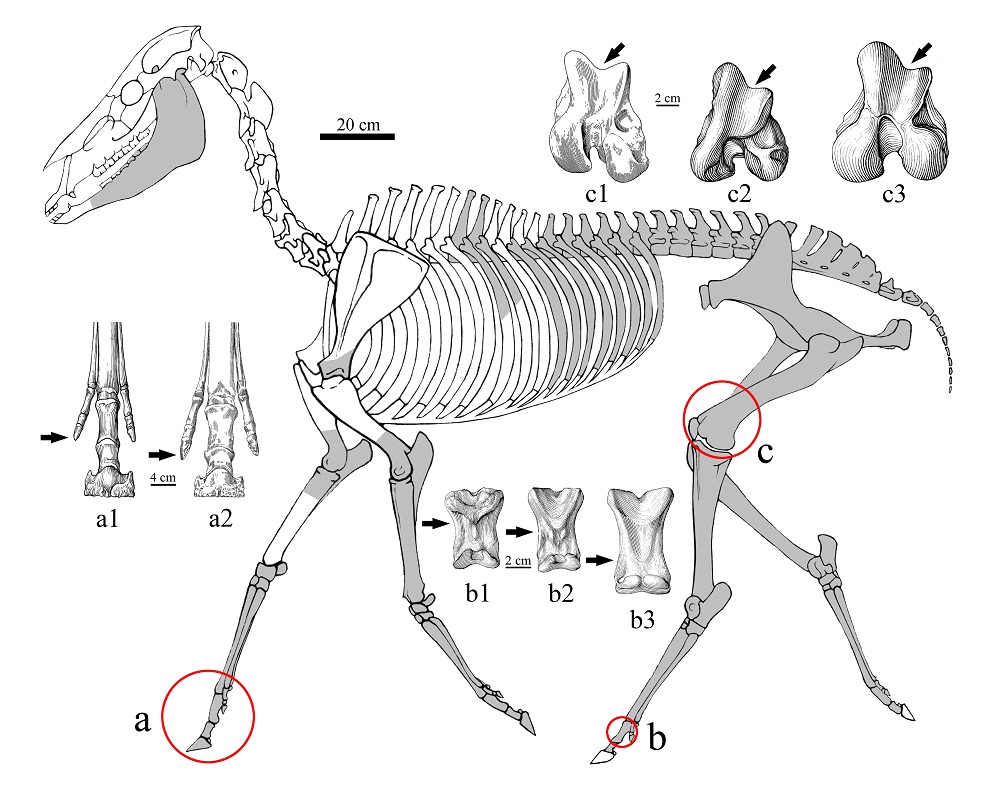

The fossilized horse bones were found in the Zanda Basin, in southwestern Tibet, near the Himalayas. The horse is about 4.6 million years old and seems to be from the three-toed horse genus Hipparion. The species was identified as Hipparion zandaense, which was originally named based on a single skull found in the late 1980s.

The new find included a majority of the horses' bones, including its legs. By analyzing the legs, they were able to get a better grip on the environment it lived in, shedding light on the state of the plateau at that time.

"These guys have pretty long legs, well-adapted to open terrain [and] running fast; it means that these guys are probably not in the wooded areas," Wang said. "By being not in the wooded areas, basically the paper concludes that the areas where the horse originally lived was above the tree lines in those days."

In this way, the Zanda horse would have been quite similar to the Tibetan wild ass, except the Zanda horse had three toes instead of the wild ass's one.

Grazing grasslands

The horse also had teeth characteristics of a grazer, the researchers said, further supporting the idea that the area was open grassland when the horse lived.

One of the researchers, Yang Wang of Florida State University, analyzed the chemicals contained within the fossils to get an idea of what kinds of grasses the horses ate. She was able to tell that these horses ate plants that were characteristic of a cold, open land similar to that seen in the Zanda Basin today.

"Those earlier horses have similar diet to the wild asses [currently] living in the area. They are grazing on grasses that are adapted to the cold," Wang said. "It’s a high elevation environment, but exactly how high we don't know."

The researchers estimate that 4.6 million years ago, when these horses roamed the area, it was about 1,300 feet (400 m) higher than the modern tree line, and probably about the same elevation as it is today.

The study was published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Monday (April 23).

Editor’s Note: The species name for the new horse is Hipparion zandaense, not Hipparion zanda.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter, on Google+ or on Facebook. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.