Bigfoot & Yeti DNA Study Gets Serious

A new university-backed project aims to investigate cryptic species such as the yeti whose existence is unproven, through genetic testing.

Researchers from Oxford University and the Lausanne Museum of Zoology are asking anyone with a collection of cryptozoological material to submit descriptions of it. The researchers will then ask for hair and other samples for genetic identification.

"I'm challenging and inviting the cryptozoologists to come up with the evidence instead of complaining that science is rejecting what they have to say," said geneticist Bryan Sykes of the University of Oxford.

While Sykes doesn't expect to find solid evidence of a yeti or Bigfoot monster, he says he is keeping an open mind and hopes to identify perhaps 20 of the suspect samples. Along the way, he'd be happy if he found some unknown species. [Rumor or Reality: The Creatures of Cryptozoology]

"It would be wonderful if one or more turned out to be species we don't know about, maybe primates, maybe even collateral hominids," Sykes told LiveScience. Such hominids would include Neanderthals or Denosivans, a mysterious hominin species that lived in Siberia 40,000 years ago.

"That would be the optimal outcome," Sykes said.

The project is called the Oxford-Lausanne Collateral Hominid Project. It is being led by Sykes and Michel Sartori of the zoology museum.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

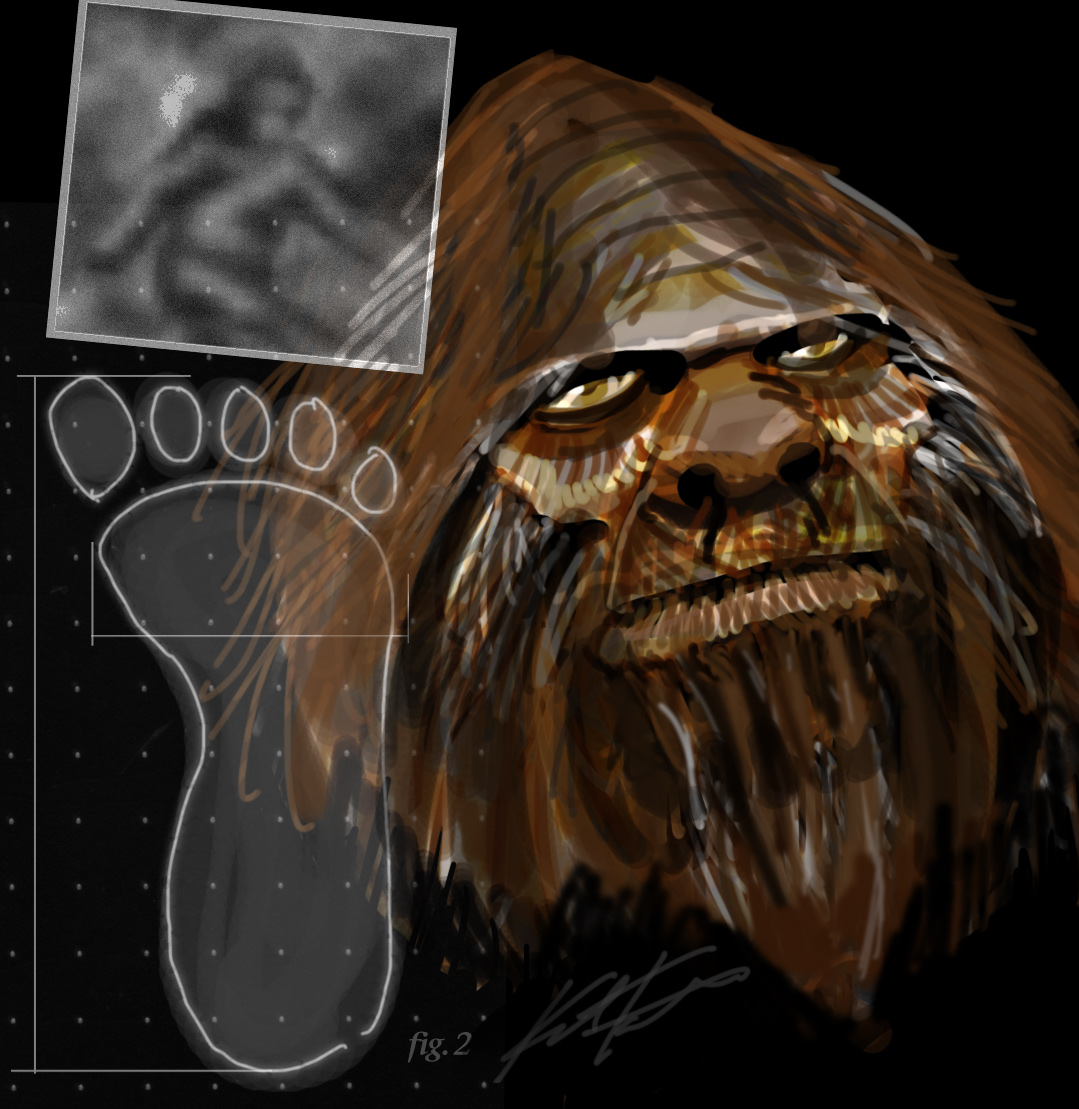

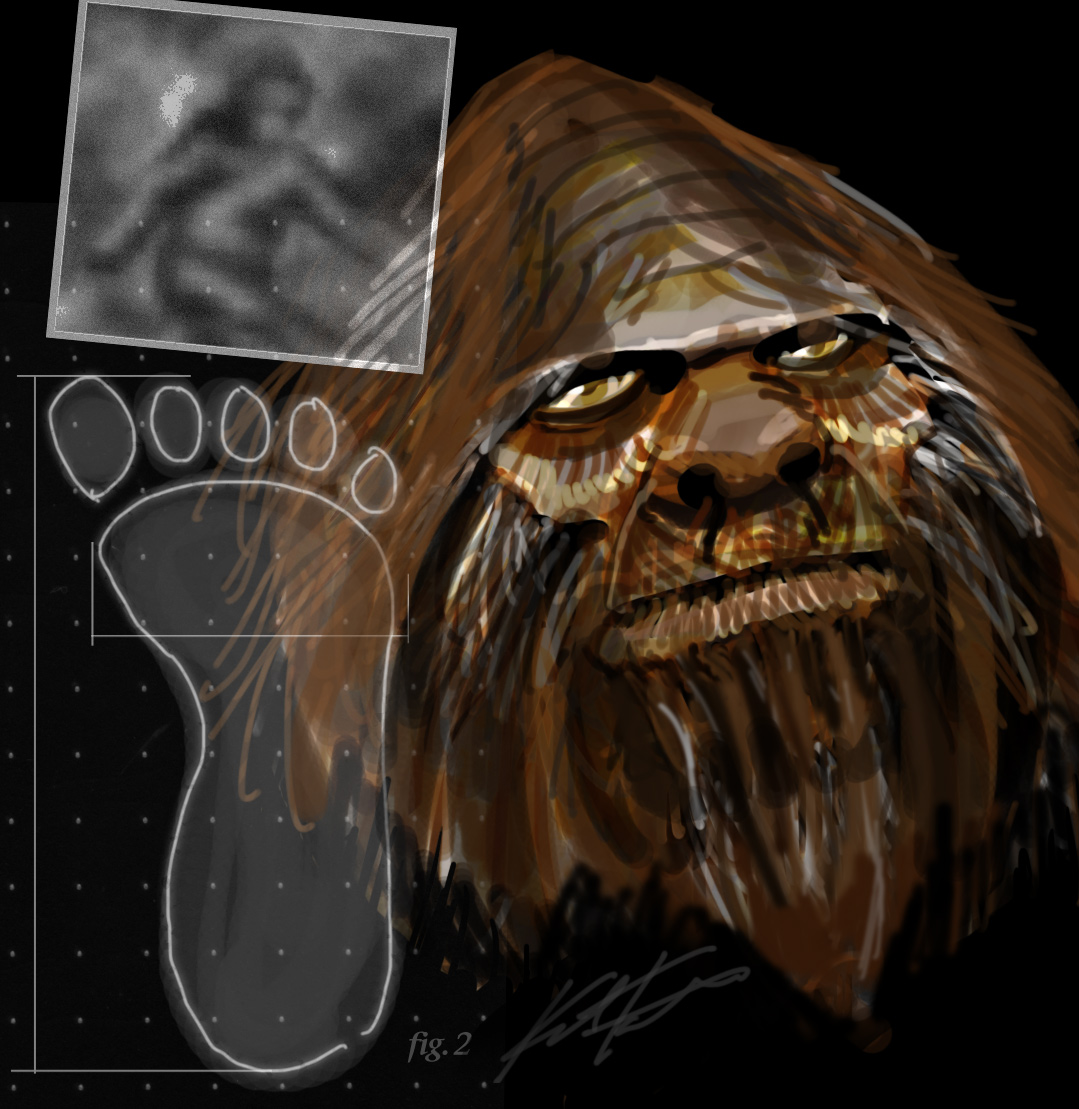

Origin of a legend

The story of a big hairy monster of the Himalayas stomped into popular culture in 1951, when British mountaineer Eric Shipton returned from a Mount Everest expedition with photographs of giant footprints in the snow.

The cryptic creature goes by many names in many places: yeti or migoi in the Himalayas, Bigfoot or sasquatch in the United States and Canada, respectively; almasty in the Caucasus Mountains; orang pendek in Sumatra. [Infographic: Tracking Belief in Bigfoot]

And while reports of such creatures have abounded around the world since then, there is no real proof they exist; the reports inevitably turn out to be of a civet, bear or other known beast.

Yeti hairs

Sykes doesn't want to start receiving loads of skin, hair and other samples haphazardly, so he is asking people to send detailed descriptions of their "yeti" samples.

Once he and his colleagues have looked over the details — including physical descriptions of the sample (even photographs), its origin and ideas about the likely species it belongs to — they will send a sampling kit for those that are deemed suitable for study.

"As an academic I have certain reservations about entering this field, but I think using genetic analysis is entirely objective; it can't be falsified," Sykes said. "So I don't have to put myself into the position of either believing or disbelieving these creatures."

One theory about the yeti is that it belongs to small relic populations of other hominids, such as Neanderthals or Denisovans. While Sykes said this idea is unlikely to be proven true, "if you don't look, you won't find it."

The collection phase of the project will run through September, with genetic testing following that through November. After that, Sykes said, they will write up the results for publication in a peer-reviewed scientific journal; this would be the first such publication of cryptozoology results, he said.

"Several things I've done in my career have seemed impossible and stupid when contemplated, but have impressive results," Sykes said. When he set out to find DNA from ancient human remains, for instance, he thought, "It's never going to work." It did, and he published the first report of DNA from ancient human bones in the journal Nature in 1989.

Ever seen Bigfoot's eyeshine in your headlights at night? Heard a splash and sworn you saw Nessie's tail disappearing below the lake surface? Cryptic creatures of myth and legend are known the world over.

Bigfoot, Nessie & the Kraken: Cryptozoology Quiz

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Editor's Note: This article as updated to correct the spelling of "orang pendek." Thanks to the reader who pointed out the error!

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.