Record Greenland Ice Melt Happened in Days

Greenland ice, it seems, can vanish in a flash, with new satellite images showing that over just a few days this month nearly all of the veneer of surface ice atop the island's massive ice sheet had thawed.

That's a record for the largest area of surface melt on Greenland in more than 30 years of satellite observations, according to NASA and university scientists.

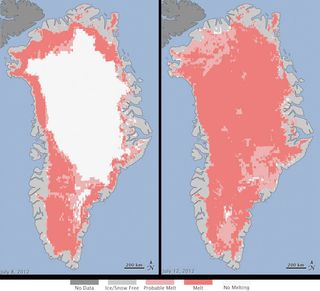

The images, snapped by three satellites, showed that about 40 percent of the ice sheet had thawed at or near the surface on July 8; just days later, on July 12, images showed a dramatic increase in melting with thawing across 97 percent of the ice sheet surface.

"This was so extraordinary that at first I questioned the result: was this real or was it due to a data error?" said Son Nghiem of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., referring to the July 12 images taken by the Indian Space Research Organisation's (ISRO) Oceansat-2 satellite.

Nghiem had reason to be baffled, as this record ice-melt is well above average: About half of Greenland's surface ice tends to melt every summer, with the meltwater at higher elevations quickly refreezing in place and the coastal meltwater either pooling on top of the ice or draining into the sea. [Giant Ice: Photos of Greenland's Glaciers]

Instruments on two other satellites proved out Nghiem's findings — the Moderate-resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA's Terra and Aqua satellites

Data from the Special Sensor Microwave Imager/Sounder on a U.S. Air Force meteorological satellite also confirmed the mind-blowing melt.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As for what caused the disappearing ice, University of Georgia, Athens climatologist Thomas Mote suggests it could be a ridge or dome of warm air hovering over Greenland that coincided with the extreme melt.

"Each successive ridge has been stronger than the previous one," Mote said in a NASA statement. The latest in a series of these heat domes, which have dominated Greenland weather since May, began to move over Greenland on July 8, before coming to a halt over the ice sheet some three days later. By July 16, the heat dome had started to dissipate.

Signs of ice melt were even found around Summit Station in central Greenland, which at 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) above sea level is near to the highest point of the ice sheet.

"Ice cores from Summit show that melting events of this type occur about once every 150 years on average," said study researcher Lora Koenig, a glaciologist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. "With the last one happening in 1889, this event is right on time," Koenig said in a statement.

The melting of such a huge ice sheet — spanning an area of 656,000 square miles (1.7 million square kilometers) — is important for various reasons, particularly its potential effect on sea levels. If melted completely, the Greenland ice sheet could contribute 23 feet (7 meters) to global sea-level rise, according to a 2007 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the international body charged with assessing climate change.

Whether or not this recent massive melt will affect the overall ice loss this summer, and as such bump up sea level, is still an open question.

Scientists say that man-made global warming, a result of greenhouse gas emissions, is contributing to Greenland ice melt. In fact, past research has suggested that the Greenland ice sheet will vanish in 2,000 years under business-as-usual carbon emissions. If humans managed to limit global warming to 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius), the disappearance would take 50,000 years.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Most Popular