5 Mars Myths and Misconceptions

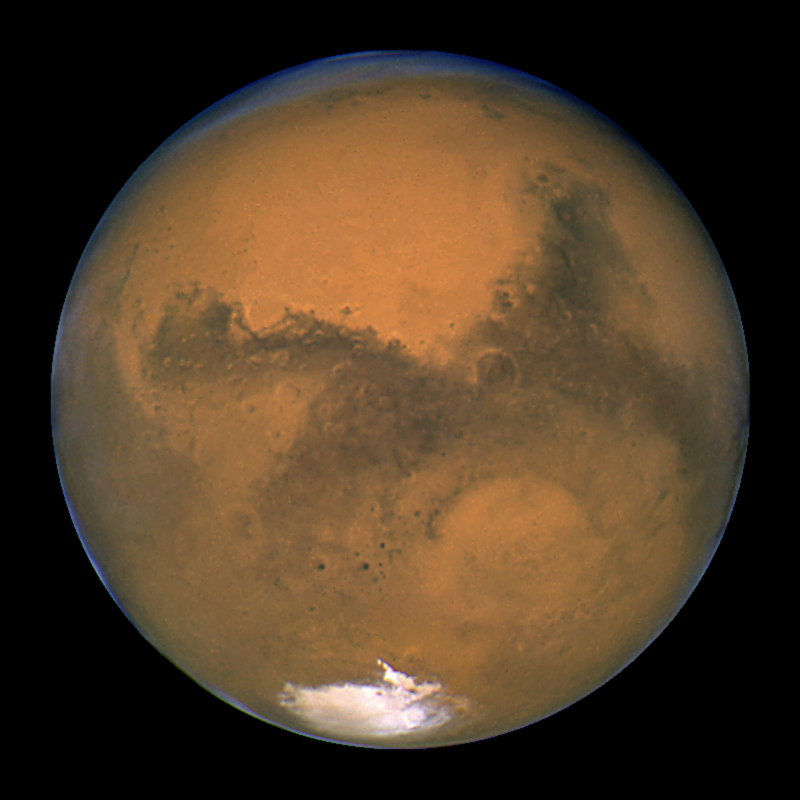

Earth's neighbor Mars is perhaps the most-studied planet beside our own in the solar system, with two robot rovers, Spirit and Opportunity, exploring the surface since 2004.

With Spirit no longer sending communications back to Earth but Opportunity still chugging along, NASA plans to land a third rover on the Martian surface; on Sunday, Aug. 5 at 10:30 p.m. PDT (1:30 a.m. EDT, 0530 GMT), Curiosity will carry 10 times the mass of scientific instruments as the earlier rovers to Mars, offering an opportunity to learn more than ever about the Red Planet.

Before Mars exploration began, though, limited information led to major misconceptions about the planet. Here are some of the myths that have persisted, and in some cases still persist, about Mars. [Full Mission Coverage of Mars Curiosity]

Myth #1: There's a face on Mars

In 1976, NASA's Viking 1 spacecraft snapped a photo of a Martian mesa that turned out rather eerie. Staring back from the surface of Mars was what appeared to be a human face.

Scientists shrugged the images of the "Face on Mars" off as a trick of light and shadow, but the public went mad. Conspiracy theorists figured the face was evidence of life on Mars. Supermarket tabloids loved it. It even showed up in a 1993 episode of television show "The X-Files" (episode: "Space").

In 1998, NASA's Mars Global Surveyor flew over the face and snapped the first sharp images of the landform since the Viking missions. This time, the mesa looked decidedly less human. The face got one more blow in 2001, when the same spacecraft snapped yet more photographs. In high resolution, the Face on Mars turns out to be an ordinary butte. [See Things on Mars: A History of Martian Illusions]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Myth #2: Martians built complex canals

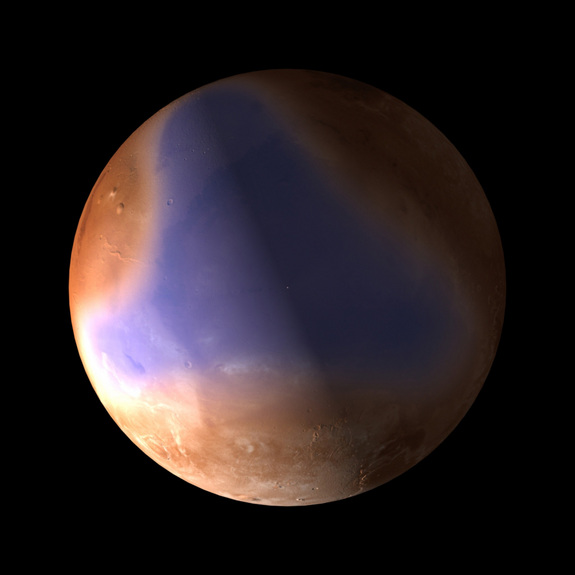

Long before the Face on Mars mystified the public, planet-gazers were convinced that strange features dotted the surface of the Red Planet. In 1877, Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli observed what he called "canali," or canals, on the Martian surface. Could these features be evidence of irrigation and civilized life?

American businessman Percival Lowell certainly thought so. His drawings of the canals and his three books on the planet published between 1895 and 1908 spread the idea that intelligent life had built the canals in a desperate attempt to draw water from Mars' polar ice caps.

The first close-up pictures of Mars in 1965, taken by the spacecraft Mariner 4, put the canal theories to bed. It turns out no such features exist, and the canals are now known to be nothing but an optical illusion.

No planet is more steeped in myth and misconception than Mars. This quiz will reveal how much you really know about some of the goofiest claims about the red planet.

Mars Myths & Misconceptions: Quiz

Myth #3: Mars has oceans

Less fanciful than the idea of canals on Mars, but still ultimately proven untrue, was the idea that Mars boasts oceans. In 1784, astronomer Sir William Herschel published a paper on his telescope observations of Mars. He got some things right, or at least close, including an axial tilt of 30 degrees (the actual number is 25.19).

But Herschel did make the mistake of assuming that the dark areas he saw on Mars were oceans, broken up by lighter regions representing land. The idea of Martian oceans would persist throughout the 1800s. Close-up looks at the planet would prove it to be arid, though some scientists think liquid water once flowed on the planet billions of years ago. As of today, the water found on Mars has all been locked up as ice in the soil, with evidence of liquid water at the surface still uncertain.

Myth #4: Mars will appear as big as the moon

Since 2003, an email forward has circulated claiming that on a certain date Mars "will look as large as the full moon to the naked eye." For extra urgency, the writer warns readers, "NO ONE ALIVE TODAY will ever see it again."

No one alive today will ever see it at all, as it turns out. In fact, Mars' orbit did bring it close to the Earth on Aug. 27, 2003, but the planet looked only six times larger and 85 times brighter than it does normally — certainly not anything close to our view of the moon. [Album: Beautiful Shots of Mars]

This close approach in 2003 was the nearest Mars has been in 60,000 years at about 35 million miles (56 million kilometers). In comparison, the moon is, on average, 238,855 miles (384,400 kilometers) from Earth. Even given its larger size, Mars would have to get pretty close to match the moon in the night sky.

Myth #5: Mars supports intelligent life

The possibility of life on Mars isn't ruled out, but these days, scientists tend to look for tiny microbes, not super-smart tentacle-armed Martians.

The latter is the more common image when going back through the history of human imagination about Mars. Sir William Herschel, a great believer in extraterrestrial life, wrote in his 1784 paper that Martians "probably enjoy a situation similar to our own." The eventually overturned canal observations sparked widespread interest in the idea of an intelligent, perhaps ancient, civilization on the planet.

Perhaps the most famous Martian "encounter" was H.G. Wells' novel "The War of the Worlds," published in 1898. In 1938, a radio adaptation of the novel spawned panic when listeners assumed the invasion described was real. Who could blame them? Just 17 years before, the New York Times published an article declaring that the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company, Ltd., had received transmissions from Mars too regular to be natural occurrences.

"Now this much is known about Mars," the NY Times quotes Marconi wireless manager J.H.C. Macbeth as saying. "Astronomers assert their belief that life can be sustained on that planet. Whether human life and whether Martians, if they exist, have eyes in their foreheads or the backs of their heads, of course, is speculation."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.