Source of Mysterious Pumice 'Raft' in Pacific Found, NASA Says

The source of an enormous floating mass of pumice spotted this week in the South Pacific Ocean off the coast of New Zealand has been discovered: NASA satellite images and other sleuthing science have pinpointed an erupting undersea volcano called the Havre Seamount as the culprit.

On Aug. 9, the HMNZS Canterbury ship observed the floating pumice "island" — measuring a whopping 300 miles (482 kilometers) in length and more than 30 miles (48 km) wide — along a voyage from Auckland to Raoul Island, New Zealand. A maritime patrol aircraft, RNZAF Orion, had seen the weird mass and reported it to this Royal New Zealand Air Force ship. Soon after, the HMNZS crew saw the thick mass of porous rocks.

"The rock looked to be sitting two feet above the surface of the waves, and lit up a brilliant white colour in the spotlight. It looked exactly like the edge of an ice shelf," said Lieutenant Tim Oscar, a Royal Australian Navy officer, in a statement.

Pumice, which forms when volcanic lava cools quickly, is riveted with pores due to gas getting trapped inside as the lava hardens. The result: lightweight rocks that can therefore float. (Recent research suggests such pumice replenishes the Great Barrier Reef with new coral.)

Where the huge floating mass came from was a mystery. At the time, according to the Royal Navy, scientists thought an underwater volcano, possibly the Monowai seamount, which has been erupting along the so-called Kermadec arc, was responsible. [See Photos of the Pumice Raft]

However, though Monowai is several hundred miles to the north of the pumice raft, and it was known to have erupted on Aug. 3, scientists have now ruled it out: An airline pilot reported seeing pumice as early as Aug. 1, according to a statement by NASA.

To finger the source, scientists looked to earthquake records and satellite imagery. New Zealand's GNS Science organization and scientists from Tahiti suggested a connection between the pumice raft and a cluster of earthquakes in the Kermadec Islands on July 17-18. (As magma rises from undersea volcanoes, pushing its way through cracks in the seafloor, the pressure can lead to earthquakes.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

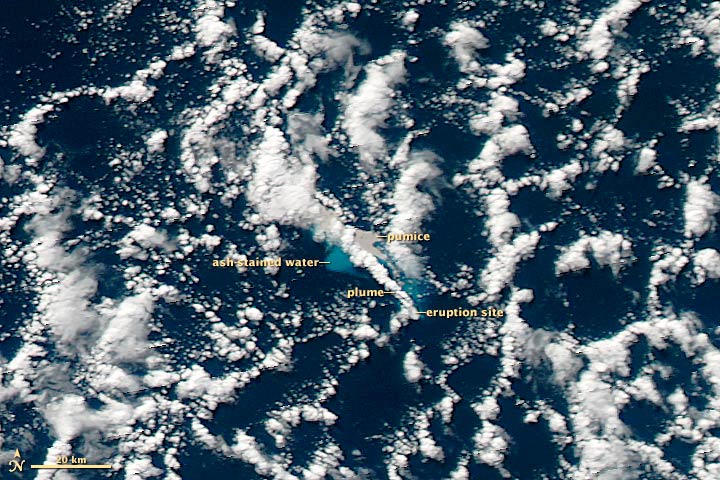

As for imagery, volcanologist Erik Klemetti, an assistant professor of geosciences at Denison University, and NASA visualizer Robert Simmon looked through a months' worth of satellite photos taken by NASA's Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) aboard the Terra and Aqua satellites. And that's where they gleaned the first evidence of the offending volcano. Images taken on July 19, from 9:50 a.m. to 2:10 p.m. local time, revealed ash-stained water, gray pumice and a volcanic plume.

By overlaying the satellite imagery onto the ocean floor bathymetry, or seafloor topography, Klemetti identified Havre Seamount as the likely source. Heat from the eruption showed up in MODIS' nighttime imagery on July 18 at 10:50 p.m. local time, according to Alain Bernard of the Laboratoire de Volcanologie, Université Libre de Bruxelles. That suggested the eruption was strong enough to breach the ocean surface from 3,600 feet (1,100 meters) below.

The Havre eruption had tapered off by July 21, leaving behind the sprawling raft of pumice. Winds and currents since have spread the porous rocks into "a series of twisted filaments," according to the NASA statement. As of Aug. 13, the pumice was spread over an area about 280 by 160 miles (450 by 258 kilometers).

Samples taken by crew aboard the HMNZS Canterbury are expected to be analyzed by GNS Science. In addition, when the Canterbury returns through the area in the next few days, "we are hoping to get some better photos or information on the 'raft' back at this time," Todd O'Hara, a press officer with the New Zealand Defence Force, told LiveScience in an email.

To seal the deal, researchers will need to observe the undersea eruption firsthand. "Now, to confirm Havre as the source, research vessels will need to head out there and try to find evidence on the seafloor for the eruption, so confirmation might take months to occur," Klemetti writes on his blog on Wired.com.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.