When Will We Learn To Speak Animal Languages?

Koko the gorilla can comprehend roughly 2,000 words of spoken English. She doesn't have a vocal tract suitable for responding verbally, so the 40-year-old ape signs her thoughts using a modified form of American Sign Language. Counting her native gorilla tongue, she is, therefore, trilingual.

And she doesn't just talk about food. Over the 28 years that gorilla researcher Penny Patterson has worked with Koko, the ape has expressed a whole range of emotions associated with humans, Patterson says, including happiness, sadness, love, grief and embarrassment.

Alex the African grey parrot could utter some 150 English words by the time of his death in 2007. The wordy bird demonstrated that he could count up to six objects, distinguish between numerous colors and shapes, combine words to create new meanings and understand abstract relational concepts such as "bigger," "smaller," "over" and "under." On the night of his death, at age 31, Alex's last words to his handler, animal psychologist Irene Pepperberg, reportedly were: "You be good. See you tomorrow. I love you."

From Chaser the border collie and Kanzi the bonobo to Akeakamai the dolphin, lab animals of many stripes have excelled at learning the rudiments of human languages. But despite the great strides these animals have made in crossing the species divide and communicating with humans in human terms, people have seldom ventured the other way.

Surely, as the most intelligent species, humans could learn to understand dolphin-speak better than dolphins learn sign language. Instead of trying to teach human communication systems to animals, why don't people decode theirs?

As it turns out, many scientists are trying. They hope to someday learn dolphin, elephant, gorilla, dog and all the other animal tongues. One scientist has already decoded a great deal of prairie dog. But researchers are off to a slow and late start down this road, because they're having to overcome a major obstacle of their own making: the idea that animals don't actually have languages.

"It's a hotly debated area, because there are still people who want to separate humans from other animals," said Marc Bekoff, professor emeritus of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Colorado, Boulder, and co-founder (with primatologist Jane Goodall) of Ethologists for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. "So if you're doing fieldwork and you see something in the animal's communication system that looks like syntax, they're going to say it isn't." [6 Amazing Videos of Animal Morality]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Prairie dog prattle

Constantine Slobodchikoff may have ventured further beyond this barrier than anyone. A professor emeritus of biology at Northern Arizona University, he has spent decades decoding the communication system of Gunnison's prairie dogs, a species native to the Four Corners region of the U.S. Southwest. Prairie dogs are rodents. They aren't particularly renowned for their smarts. And yet, in dozens of books and articles over the past three decades, Slobodchikoff and his colleagues have laid out extensive evidence that prairie dogs have a complex language. And he can understand a lot of it.

When they see a predator, prairie dogs warn one another using high-pitched chirps. To the untrained ear, these chirps may all sound the same, but they aren’t. Slobodchikoff calls the alarm calls a "Rosetta stone" in decoding prairie-dog language, because they occur in a context people can understand, enabling interpretation.

In his research, Slobodchikoff records the alarm calls and subsequent escape behaviors of prairie dogs in response to approaching predators. Then, when no predator is present, he plays back these recorded alarm calls and films the prairie dogs' escape responses. If the escape responses to the playback match those when the predator was present, this suggests meaningful information is encoded in the calls.

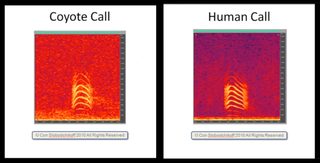

And indeed, there seems to be. Slobodchikoff has discovered the rodents have distinct calls pertaining to different potential predator species, such as coyotes, humans or domestic dogs. Their calls even specify the color, size and shape of the predator; for example, they'll differentiate between an overweight, tall human wearing a blue T-shirt and a thin, short human wearing green. [Video: Prairie Dog Alarm Calls]

Remarkably, the prairie dogs even create new alarm calls in response to foreign objects introduced by the researchers, such as a picture of a large black oval. Although the prairie dogs never would have had cause to discuss such an object previously, they all generate an identical alarm call in response to it, suggesting they are describing the oval’s size, shape and color in a standard way.

And just like different groups of humans, different species of prairie dogs have distinct dialects. The Gunnison's prairie dogs that Slobodchikoff studies are unlikely to understand the calls of Mexican prairie dogs, Slobodchikoff said.

Their communication goes beyond alarm calls. “Prairie dogs also have what I call social chatters, where one prairie dog will produce a string of vocalizations, and another prairie dog across the colony will respond with a different string of vocalizations,” Slobodchikoff told Life’s Little Mysteries. "I can show that there seems to be some syntax in these strings, but since nothing about the behavior of the prairie dogs changes, I can't say anything about the context, and so I have no way of decoding the possible information contained in these [social] chatters." [Rats Are Ticklish, and Other Weird Animal Facts]

In his new book, "Chasing Doctor Dolittle: Learning the Language of Animals" (St. Martin's Press), scheduled for release on Nov. 27, Slobodchikoff lays out his and other scientists' latest efforts to learn animal tongues.

Dolphin-speak

If animals seemingly as simple as rodents have a language replete with nouns, adjectives, syntax and dialects, think what higher-order animals might be saying.

Elephants hold funerals for their dead and have been known to orchestrate raids on human villages in retaliation for poaching. Chimps wage wars. Complex animal behaviors like these necessitate complex languages, Bekoff said. "People wonder, 'How do wolves coordinate their hunts?' It's by having really complex communication systems."

Consider dolphins. They form strong social bonds, and a recent study found they even display culture, preferring to socialize with other dolphins that use the same simple tools as they do. Dolphins also make a variety of vocalizations, such as clicks and whistles. Those aren't likely to be meaningless. So will people ever learn what they're saying?

It turns out scientists have been trying to do so for over half a century. "We know a lot more than we knew a few decades ago, but we're still a long way from two-way communication," said Stan Kuczaj, director of the Marine Mammal Behavior and Cognition Laboratory at the University of Southern Mississippi.

Kuczaj said the major stumbling block has been figuring out what the units of dolphin communication are.

Monosyllabic sounds and other "phonemes are the building blocks of human languages," Kuczaj told Life’s Little Mysteries. "We don't know what the building blocks of dolphin communication systems are. Are they whistles, clicks? We now know they use touch and posture as well. My guess is we'll learn more about the units by studying the development of communication in dolphin calves. And then the next level is, what do the combinations of the units mean?"

Denise Herzing and colleagues at the Wild Dolphin Project have discovered that dolphins seem to address each other with names — vocalizations that the researchers call "signature whistles." These would suggest the whistles are units of communication, but how dolphins' clicks and postures enter in remains to be determined.

Kuczaj thinks we may eventually crack the code, but not everyone agrees there's a code to be cracked. Justin Gregg, a researcher with an international dolphin research organization called the Dolphin Communication Project, thinks dolphins may not have units of language at all.

"After 50 years of studying dolphin communication, it does not seem that dolphins are producing wordlike vocalizations that we can then 'decode' in the way you might think of when you think of 'learning' a foreign language or 'deciphering' Egyptian hieroglyphics," Gregg said. "This is because animal communication systems and human language are very different. Dolphin communication does not likely contain wordlike 'symbols' or 'grammar' in the way we think of human language. At present, there is no reason to believe that dolphin communication functions like human language, and thus there is no 'language' there for us to learn in the first place."

Only time will tell if that distinction between communication and language bears out. After all, if prairie dogs have the loquacity to describe an unnatural black oval in their midst, then many scientists think a surprising number of other social animals probably do as well.

This story was provided by Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover or Life's Little Mysteries @llmysteries. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.