Gut Infections May Be Linked to Inflammatory Bowel Disease

A gastrointestinal infection can send the immune system into overdrive, new research finds, causing immune cells to target beneficial gut bacteria as well as the bad.

The findings in mice suggest, but do not prove, a potential link between gut infections and the later development of inflammatory bowel disease such as Crohn's.

More work is needed to establish that connection, but it's possible that long-lived immune cells could cause problems over time, said study researcher Timothy Hand, a postdoctoral researcher at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease.

"It's a really interesting first step to say that the immune system doesn't discriminate between the bacteria in your gastrointestinal tract and any infections that come through," Hand told LiveScience.

Good gut bacteria

The gut is home to thriving communities of beneficial bacteria, living in symbiosis with their host (that would be you). These bacteria provide nutrients and conduct metabolic functions that our own bodies cannot. Thus, they're crucial to a person's health.

But the gastrointestinal tract is also a common site of infection, Hand said. He and his colleagues were interested in how the immune system deals with these nasty invaders while still tolerating the good bacteria in the gut.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To find out, the researchers infected mice with Toxoplasma gondii, a parasitic protozoa that prefers to live out its life cycle in cats and rodents, but can infect an array of warm-blooded animals. They then tracked the consequences for the mice's gut bacteria and immune systems. [10 Most Disgusting & Diabolical Parasites]

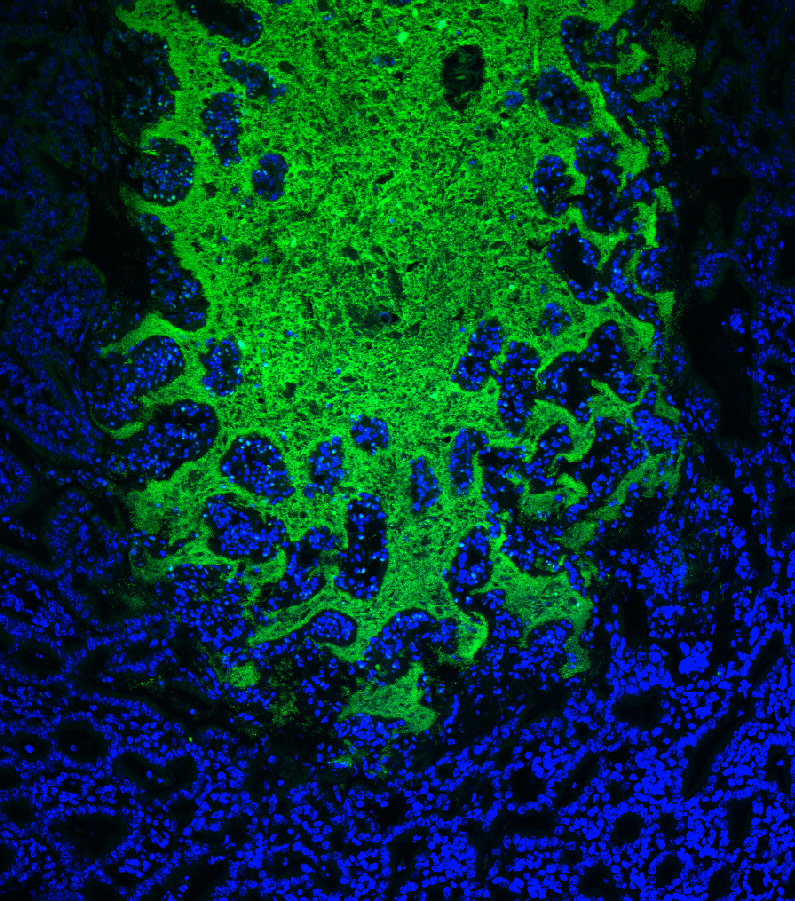

They found that the infection spurred good gut bacteria to act in odd ways. The bacteria went into overgrowth mode, invading areas of the body where they're not normally found. "Good" bacteria showed up in the mouse bloodstream, as well as the liver and spleen, Hand said.

The immune system, in turn, mounted a defense against not only T. gondii, but also against the rogue beneficial bacteria.

"The immune system treated everything as if it were an infection," Hand said. "Both the parasite and the bacteria, which happened to be inhabiting the same places."

Inflammation and Crohn's

Most likely, Hand said, the immune system is indirectly responsible for spreading the good gut bacteria around. A strong immune response can damage body cells, including the gut cells that usually keep beneficial bacteria on the inside of the intestines.

Once the parasite infection is over, the researchers found, the immune system locks in a memory of the invaders it fought in memory T cells. These cells are able to mount a fast immune response if they encounter the same pathogens for a second or third time.

Unfortunately, the T cells remember the beneficial gut bacteria as well as the parasite, the researchers report online today (Aug. 23) in the journal Science. This memory seems to last as long as the mouse lives, Hand said.

The finding suggests a possible link to Crohn's disease, a chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract usually centered in the intestines. Symptoms range from abdominal cramps to constipation to diarrhea. The exact cause is unknown, but Crohn's is an autoimmune disease, meaning that the immune system begins attacking the body.

It's possible that early severe GI infection could prime the body with memory immune cells that learn to attack good gut bacteria, Hand said. Over time, repeated infections could strengthen the response to the point of chronic, autoimmune, inflammation.

Hand warned that this link is only a hypothesis. He and his colleagues are conducting further experiments to explore the possibility.

"We'd like to know more about the initiation of this [Crohn's] disease and would like to know whether these GI infections are linked to disease," Hand said.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Flu: Facts about seasonal influenza and bird flu

What is hantavirus? The rare but deadly respiratory illness spread by rodents