Cancer: Facts about the diseases that cause out-of-control cell growth

Learn facts about cancer, in which abnormal cell growth destroys healthy body tissues.

Causes: Genetics, environmental exposures, aging, modifiable lifestyle factors

Types: More than 200

Treatments: Surgery, therapies and medications

There are tens of trillions of cells in the human body, and new cells are constantly forming as older cells age and die. But sometimes, cell growth and replication doesn't stop when it should. These abnormal cells multiply too quickly, harming healthy tissue and interfering with bodily functions. This runaway cell growth and accumulation of abnormal cells is called cancer.

There are more than 200 types of cancer, with about 20 million new cases of cancer diagnosed globally each year. The most common type of cancer worldwide is lung cancer, which causes 1.8 million deaths annually. Of any cancer, lung cancer kills the most people worldwide each year.

The earliest mention of cancer in Homo sapien history (though it was not yet called by that name) dates to about 3000 B.C. A medical textbook from ancient Egypt, known as the Edwin Smith Papyrus, documented eight cases of breast tumors. The term "cancer" arose during the first century A.D. from the Latin word for "crab," which refers to the shape of certain cancerous tumors.

Modern cancer treatment options vary depending on several factors, including the age and overall health of the patient; the type of cancer; and the stage of disease. For some cancers, doctors may recommend a single treatment strategy, while others can require multiple treatments.

Treatments include surgeries to remove cancerous growths; medications that target specific cancer proteins; and chemical or radiation therapies to shrink tumors and stop the cancer from spreading. For some cancers, there are also treatments that harness the patient's immune system to fight cancer, called immunotherapies.

Everything you need to know about cancer

What causes cancer?

Cancer is caused by changes in cells' DNA that lead those cells to multiply uncontrollably. In most cases, a combination of factors causes cancers to develop.

Some of these cancerous mutations in DNA are inherited, while others arise from errors that occur as a cell divides. Inherited genetic mutations raise the risk that certain types of cells could become cancerous; they don't guarantee that a given carrier will get cancer.

Environmental factors, such as being exposed to harmful radiation or chemicals in pollutants, can also damage DNA and cause cancer.

The risk of cancer goes up with age, in part because aging impedes the body's ability to detect and destroy cells with damaged DNA. Aging also comes with cumulative damage to cells; low-grade, chronic inflammation; and lower immune activity, which all raise cancer risk.

Adult and childhood cancers often affect different types of cells. In adults, the cells that typically become cancerous are epithelial cells, which line the body's internal and external surfaces. Cancers that affect children tend to originate in stem cells — cells that can develop into different types of body tissue and are important for maintaining tissue health and repairing damage.

Who is at risk of cancer?

Anyone can develop cancer at any age; the youngest known person with cancer was diagnosed as a newborn. A minority of cancer cases — only about 5% to 10% — are related to genetic mutations passed down through generations. Such inherited mutations raise the risk of a person developing certain cancers.

A wide range of cancers have been linked to inherited mutations, including some cases of breast cancer, uterine cancer, prostate cancer, bone cancer, and some types of leukemia and lymphoma.

Overall, cancer rates are higher in men than in women, and cancers in men are more likely to be fatal.

Certain risk factors are associated with cancer, and longer, more frequent encounters with those risk factors increase the likelihood that someone will develop the disease. For instance, cancer may manifest in an otherwise healthy person after they are exposed to radiation, chemicals or certain viral infections. In communities that are located near environmental hazards, such as factories or power plants that generate pollution, residents may be at a higher risk for developing cancer.

There are also modifiable lifestyle factors that can increase the risk of cancer. For example, prolonged exposure to the sun's ultraviolet rays without adequate sunblock can raise the risk for skin cancer. Frequent use of tobacco, including cigarette smoking, is linked to cancers of the lungs, larynx (voice box), mouth and esophagus, as well as to cancers in other parts of the body. Diets that include lots of red meat and processed foods are associated with colorectal cancer and stomach cancer. There are 13 types of cancer that are linked to obesity, including cancers of the liver, kidneys, colon and thyroid.

What are the symptoms of cancer?

Symptoms of cancer can vary, depending on how advanced the cancer is and where in the body it appears. General symptoms include fatigue, persistent pain, unexplained weight loss, loss of appetite, fever and night sweats, blood in the urine or stool, and bruising or bleeding with no clear cause.

However, these symptoms do not necessarily indicate cancer in all cases because they also appear in other diseases.

Other symptoms point to specific types of cancer. For instance, moles that change in size, shape or texture could be signs of skin cancer. Lumps in breast tissue or skin changes around the nipple could indicate breast cancer, which affects both males and females. Persistent mouth sores can be caused by oral cancers. Chronic headaches that fail to respond to normal medications can be a sign of brain cancer.

Cancer symptoms tend to intensify as the cancer becomes more advanced. Early detection of the disease greatly improves recovery outcomes, and symptoms that are suspected of being caused by cancer should be shared with a health care provider as soon as possible, experts advise.

How is cancer diagnosed?

There is no single test for cancer. However, several techniques can help doctors identify signs of the disease.

Cancer screenings are tests intended to find early signs of cancer before symptoms of the disease appear; if any signs are detected, a person will typically get further tests to be formally diagnosed. Some tests are used for both screening and diagnosis.

Screening usually starts with a physical examination, in which a health care provider inspects the patient's body for anything unusual. Health care providers may then collect samples of blood, mucus, urine or tissues for lab analysis to look for cancer cells.

Tissue samples, also known as biopsies, can be collected with a needle, a tube called an endoscope, or surgical tools. Blood tests are helpful for finding cancers such as lymphoma, leukemia and myeloma — cancerous tumors in bone marrow, the fatty tissue in the hollows of bones. Urine tests can reveal signs of bladder cancer or pancreatic cancer, and stool tests can find colorectal cancer.

Doctors rely on various types of imaging technologies for viewing cancers inside the body. These techniques include MRI, which creates pictures of body parts using radio waves; ultrasound, which uses high-energy sound waves to generate images; and X-rays. An endoscopy — a procedure that uses a flexible tool inserted into the body — can reveal signs of cancer in the digestive system, when inserted into the rectum.

For people with a family history of cancer, genetic testing can clarify if they are at heightened risk of the disease before they develop any symptoms.

What are the treatments for cancer?

There are many types of cancer treatments, and they are often used in combination. Treatments that target tumors or specific body regions are known as "local" treatments. These include surgery and some types of radiation. "Systemic" treatments, such as chemotherapy, affect the entire body.

These are some common cancer treatments:

Surgery: When cancer is concentrated in a specific part of the body as a solid tumor, surgery to remove the growth may eliminate the cancer. In some cancers, such as breast cancer, vulnerable tissue that is not yet cancerous also may be removed as a preventive measure.

Radiotherapy: Radiation therapy, or radiotherapy, kills cancer cells and shrinks tumors by exposing them to high doses of radiation, which damages the cancer cells' DNA. Treatment usually involves multiple sessions that can span weeks.

Chemotherapy: During chemotherapy, patients receive regular doses of medication aimed at shrinking tumors and slowing or stopping the growth of cancer cells by interfering with their life cycle. Chemotherapy can be given orally as pills, through an IV, as a cream rubbed into the skin, or via injection. Chemotherapy affects all cells throughout the body, not just cancer cells. As a result, chemotherapy can cause side effects such as hair loss, fatigue and nausea.

Hormone therapy: Cell growth in some cancers, such as some types of breast cancer and prostate cancer, relies on hormones, and these cancers can be treated with hormone therapy. Also known as endocrine therapy, these treatments either block the body's ability to produce specific hormones that are fueling the cancer or disrupt the behavior of those hormones. Hormone therapy can slow or stop the growth of some cancers and can ease symptoms.

Immunotherapy: Cancer cells are tricky for the immune system to detect and destroy because they resemble healthy cells in many ways and can also "mask" themselves, to hide from the immune cells. Immunotherapy assists the immune system in spotting and attacking cancer. This can be done with medications, which help the immune system recognize and attack cancer cells. Immunotherapy drugs can also weaken cancer cells so the immune system can destroy them more easily. Immunotherapies also include therapies that remove and tweak a patient's own immune cells; lab-made immune proteins called antibodies; and so-called cancer vaccines.

Stem cell treatments, or blood-marrow transplants: Blood cancers are often treated with high doses of radiation or chemotherapy, which destroy the stem cells that form blood. Stem cell treatments, including bone marrow transplants, can help to restore these essential cells.

Other cancer treatments include photodynamic therapy, a procedure that kills cancer cells with a drug activated by light; and hyperthermia treatment, another option that damages or kills cancer cells using heat. Hyperthermia, or thermotherapy, may use heating techniques such as ultrasound, lasers or radio waves.

Cancer glossary

- Tumor: A solid mass created by the uncontrolled growth of cells in a bodily tissue

- Biopsy: A procedure that removes small samples of body tissues or fluids for analysis

- Metastasize: When cancer cells spread from their place of origin to other parts of the body

- Complete remission: A person's cancer is responding to treatment, that they have no signs or symptoms of the disease, and there are no cancerous cells in their body that can be detected by a scan or a blood test

- Partial remission: A person's cancer treatment is working but that tests show some cancerous cells remain in the body

Cancer pictures

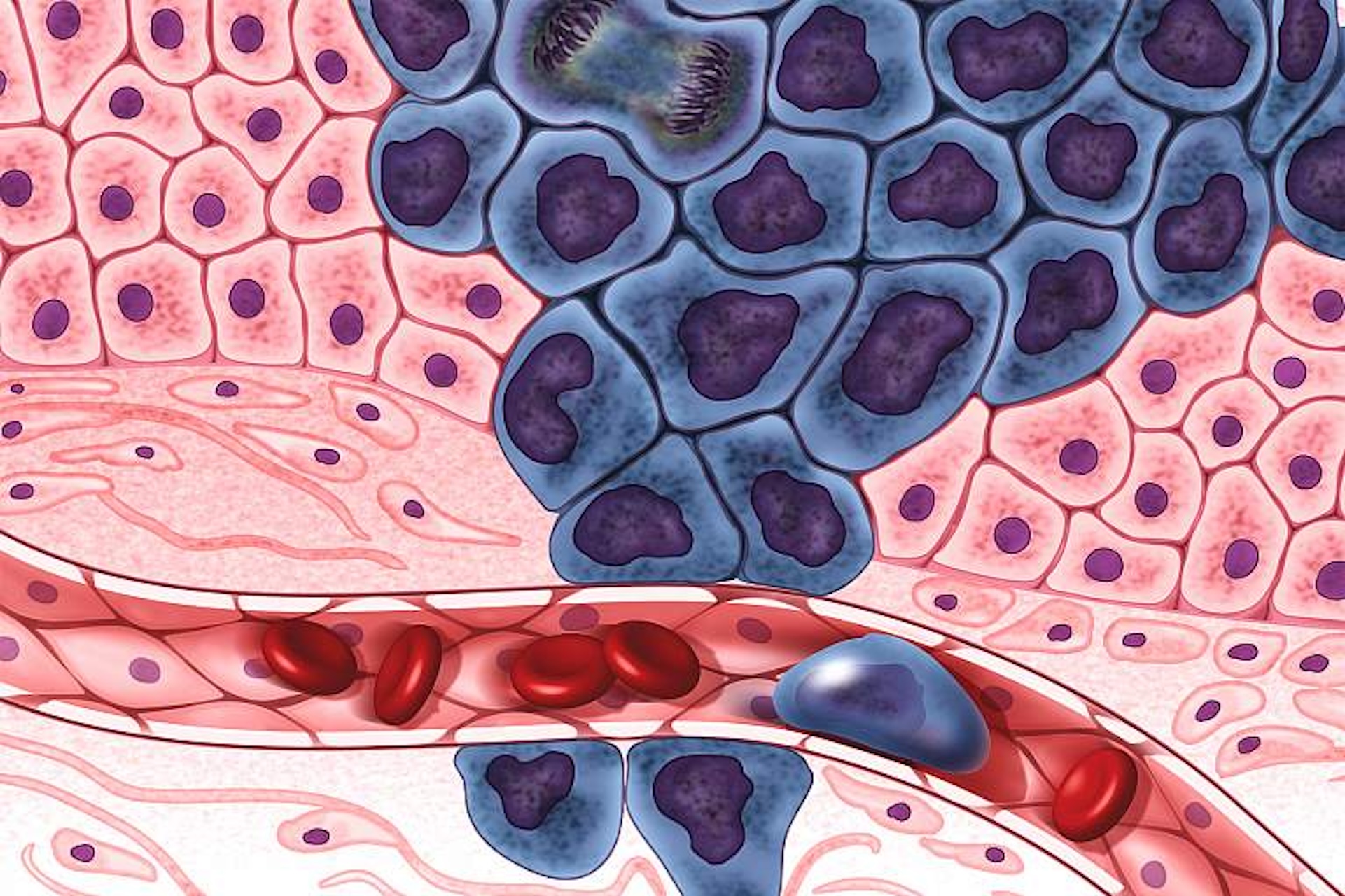

Growth of a tumor

Growing cancer cells (in purple) are surrounded by healthy cells (in pink), illustrating a primary tumor spreading to other parts of the body through the circulatory system.

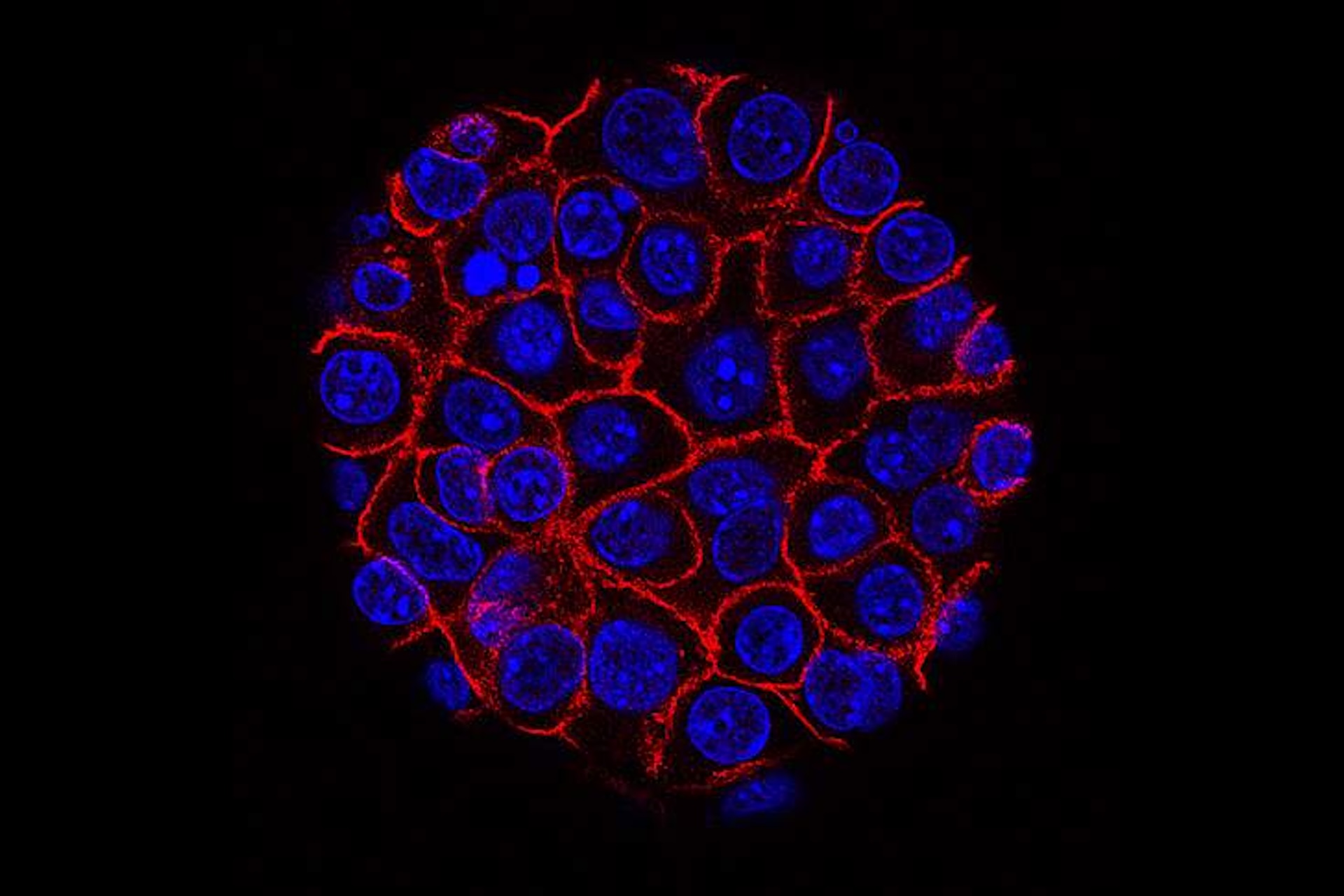

Pancreatic cancer

This image shows pancreatic cancer cells (nuclei in blue) growing as a sphere encased in membranes (red). By growing cancer cells in the lab, researchers can study factors that promote and prevent the formation of deadly tumors.

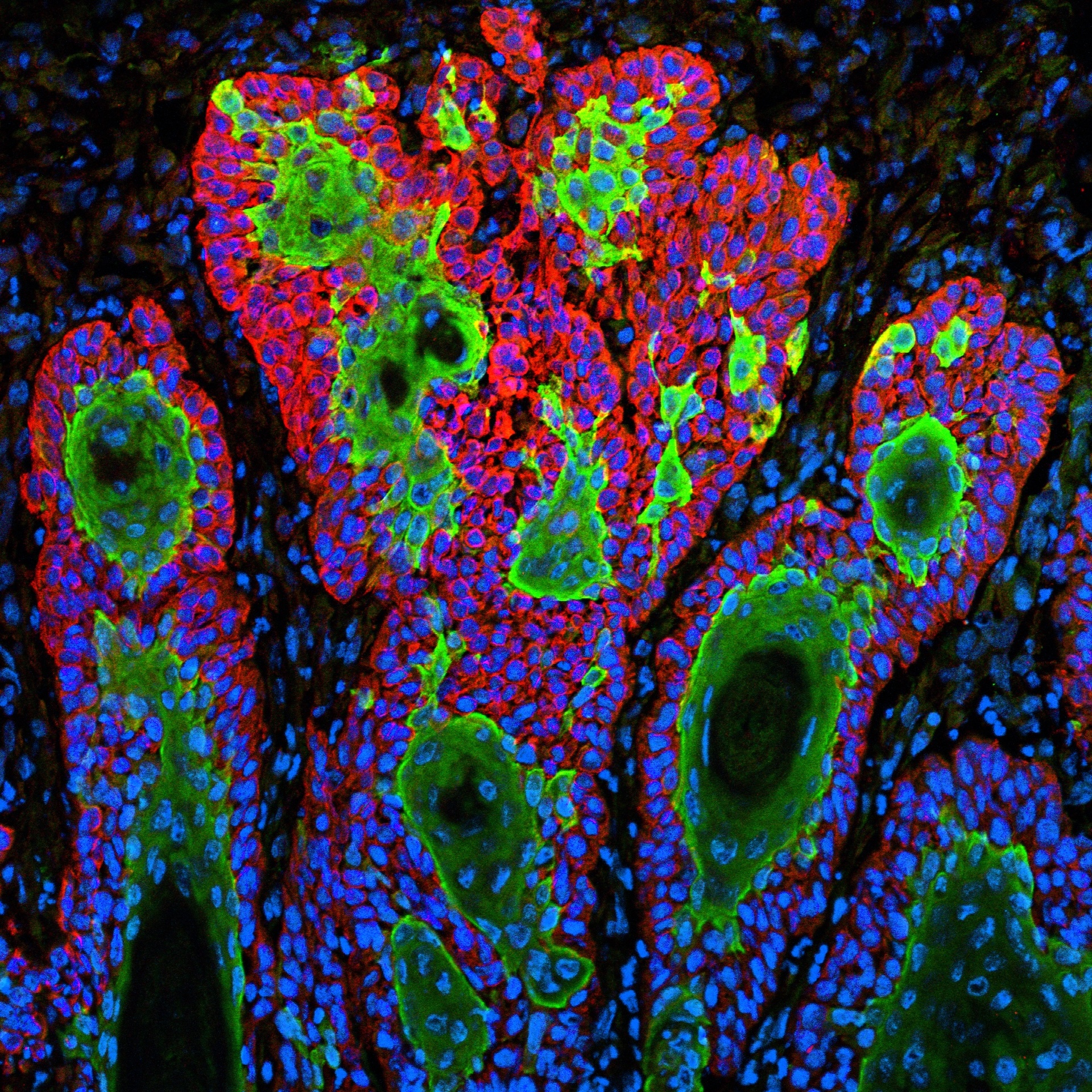

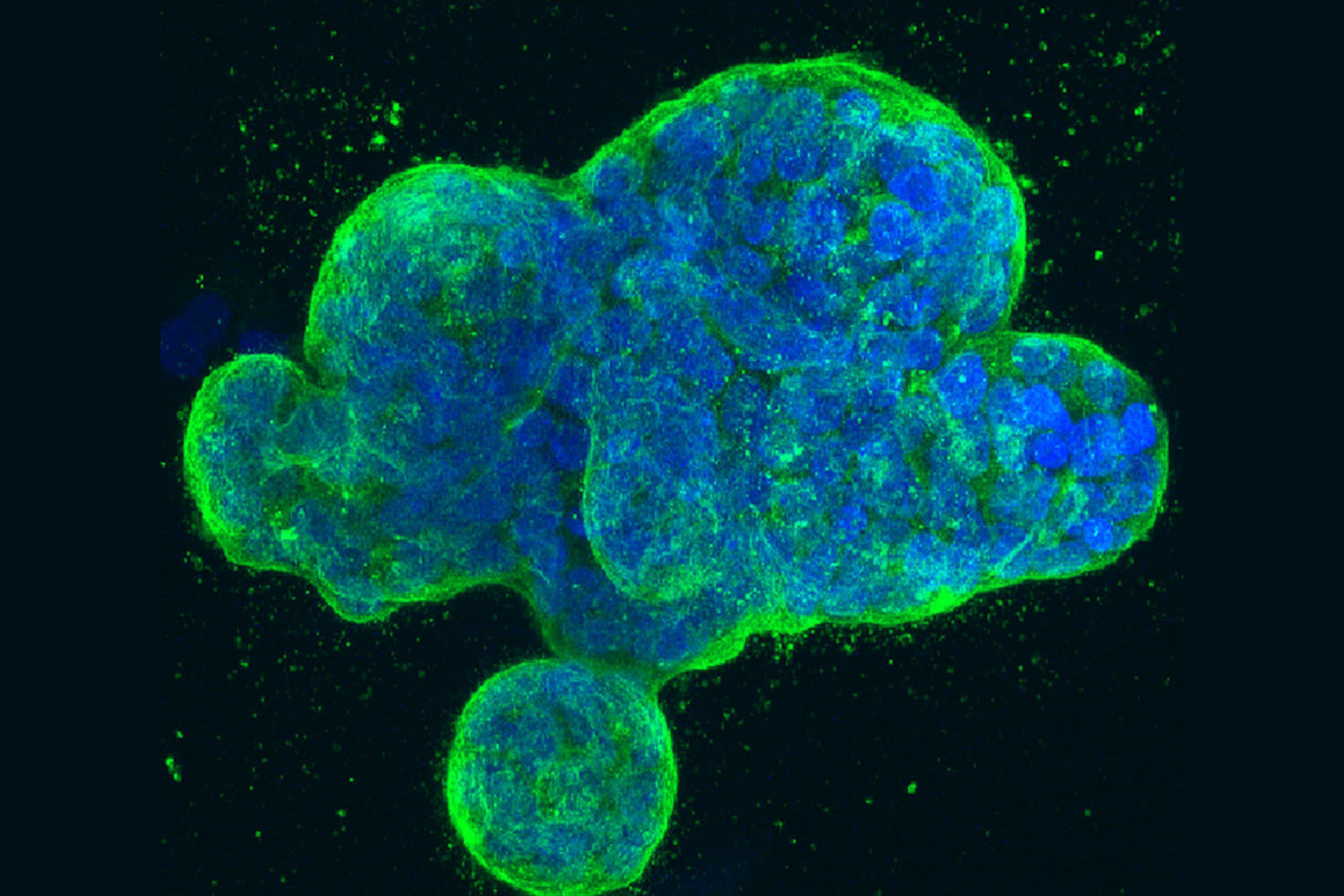

Breast cancer cells

A three-dimensional culture of human breast cancer cells, with DNA stained blue and a protein in the cell surface membrane stained green. The cancer in these cells is driven by the HER2 gene (also known as ErbB2).

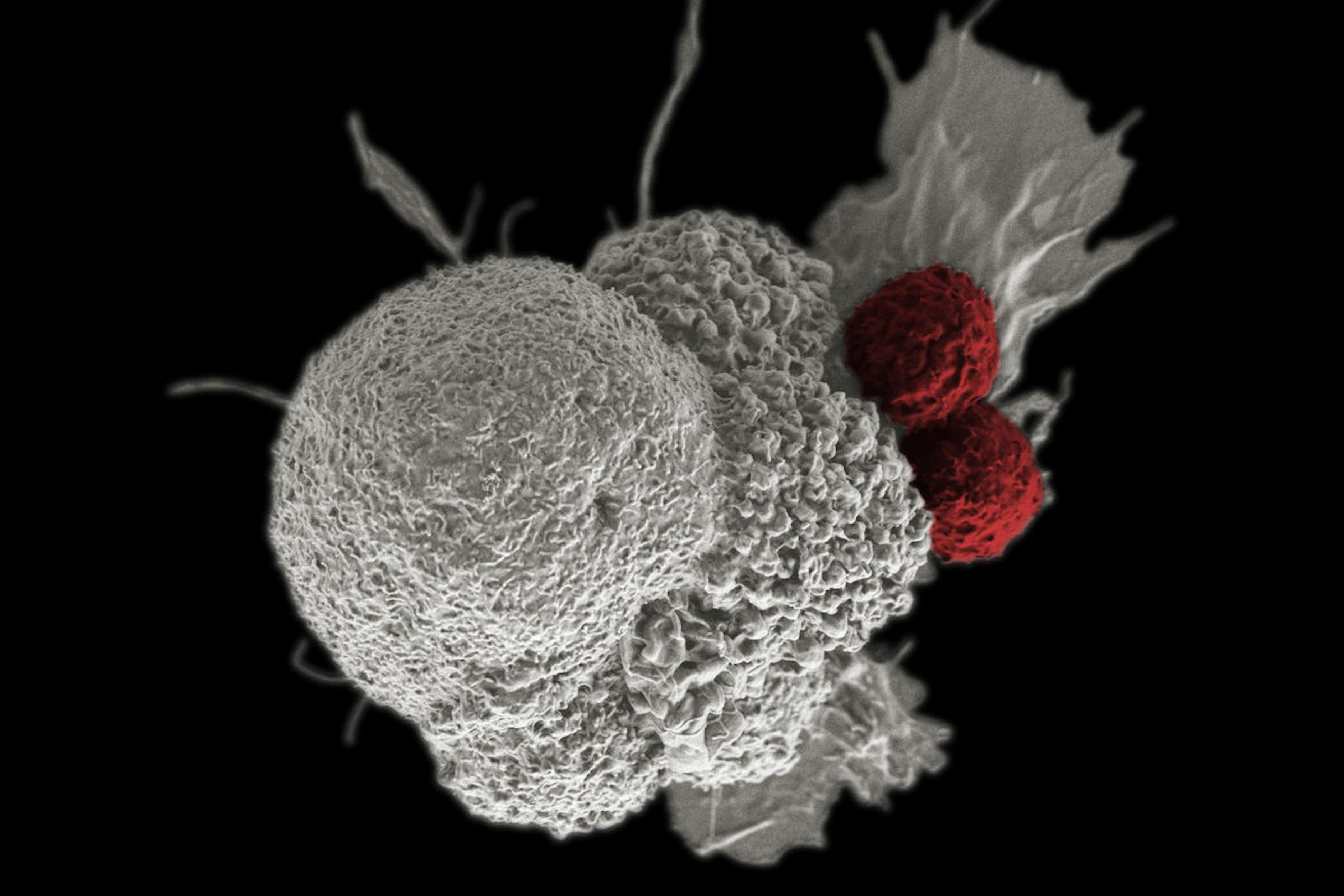

Oral cancer cell

This image shows an oral cancer cell (white) being attacked by two white blood cells (red). The tumor-fighting cells were developed from the patient's own immune system.

Discover more

—When is cancer considered cured, versus in remission?

—The 10 deadliest cancers, and why there's no cure

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works. She is the author of the book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control," published by Hopkins Press.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.