Life on Ice: Gallery of Cold-Loving Creatures

Ice Amphipod

This crustacean, an amphipod called Eusirus holmii, has been found living on Alaskan sea ice as well as in the deep ocean.

Ice Cod

An Arctic cod rests in an ice-covered space in the Beaufort Sea, North of Point Barrow, Alaska.

Shell-less Snail

Clione, a shell-less snail known as the Sea Butterfly swims in the shallow waters beneath Arctic ice, Alaska.

Polar Bears on Arctic Ice

A baby polar bear follows its mother across Arctic ice.

Ice fish

Ice fish are one of the few fish species that doesn’t let frigid temperatures get under their skin. Ice fish possess a natural antifreeze chemical in their blood and body fluids that allow them to survive the freezing, ice-laden waters surrounding the Antarctic.

Caml Ice Fish

A self-made antifreeze keeps this Antarctic icefish alive.

Penguin Pomp: Birds of a Feather

A flock of gentoo penguins at the Tennessee Aquarium in Chattanooga puts on a show. At heights of almost 3 feet (1 meter), gentoos are the third-largest penguin species in the world. Gentoos build nests out of round, smooth stones, which are highly prized by females. To curry favor with a potential mate, male gentoos sometimes present "gifts" of these coveted rocks.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What Big Paws You Have

A researcher examines the paws of a sedated polar bear in this 1982 photograph taken in Alaska. Polar bears' giant paw pads help them keep traction on ice and snow.

Ice-cold Adapter

Even in the chilliest water, life can thrive. This Antarctic ice fish, photographed during an Alfred Wegener Institute Polarstern mission, has no red blood cells or red blood pigments. The adaption makes the fish's blood thinner, saving energy that would otherwise be needed to pump the blood around the body.

Cold Crustacean

This shy-looking critter is an inhabitant of Antarctica first found during the research vessel Polarstern's ANTXXIII-8 cruise. Found in water near Antarctica's Elephant Island, the arthropod is about 1 inch (25 mm) long.

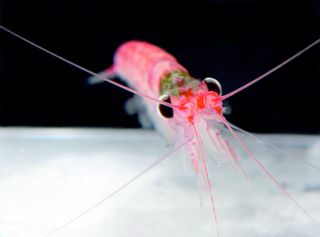

The Pink Lady

Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) plays a key role in the food webs of the South Ocean. In fact, throughout their evolutionary history, these tiny crustaceans have developed many biological rhythms that are closely connected to large seasonal changes in their environment.

But how will marine organisms like the krill react to environmental changes at the poles, such as receding sea ice and ocean warming, given that their vital processes, such as reproduction cycles and seasonable food availability, have been synchronized with the environment over millions of years? To answer this question, researchers in the virtual Helmholtz Institute PolarTime are taking a very close look at Antarctic krill, which serves as a model organism for a polar plankton species that has adapted to the extreme conditions. The Helmholtz institute is part of the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.