Giant Viruses Are Ancient Living Organisms, Study Suggests

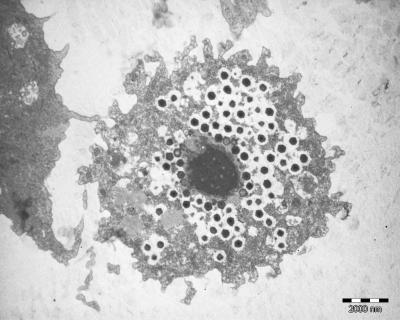

Researchers have debated whether viruses, which have genes but no cellular structure, should be considered forms of life. A new study suggests they should, showing that giant viruses have some of the most ancient protein structures found in all organisms on the planet.

The researchers conducted a census of all the protein folds occurring in more than 1,000 organisms in the three traditional branches on the tree of life — bacteria, microbes known as archaea and eukaryotes. Giant viruses, which are considered "giant" based on the size of their genomes, also were included in the study because they are large and complex, with genomes rivaling some bacteria, University of Illinois researcher Gustavo Caetano-Anollés said in a statement.

For instance, the ocean's largest virus, a giant virus called CroV, has genes that let it repair its genome, make sugars and gain more control over the very machinery the virus hijacks in host cells to replicate itself. (Since viruses are essentially DNA wrapped in a protein coat, they need the goods of a host to replicate themselves.)

Caetano-Anollés said his team looked at protein folds instead of genetic sequences because these structural features are like molecular fossils that are more stable over time. They assumed the folds that appear more often and in more groups are the most ancient structures.

"Just like paleontologists, we look at the parts of the system and how they change over time," Caetano-Anollés said.

They found that many of the most ancient protein folds in living organisms were present in the giant viruses, which "offers more evidence that viruses are embedded in the fabric of life," Caetano-Anollés said. The tree his team created had four clear branches, each representing a distinct "supergroup" — bacteria, archaea, eukaryotes and giant viruses.

The researchers said the study, which was published in the journal BMC Evolutionary Biology, also bolsters claims that giant viruses were once much more complex than they are now. A dramatic decline in their genomes over time likely reduced them to their current parasitic lifestyle, Caetano-Anollés said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.